|

Brian A. Wren, our local hymn writer, was born in Romford, Essex in 1936. His hymns are known throughout the world and have been influential in raising awareness of theology. So far, Wren has written around 250 hymns, many of which are familiar in our church.

Wren initially served in the British army for two years before attending Oxford University where he earned a degree in Modern languages in 1960, followed by a degree in Theology in 1962. After this, Wren studied for a PhD in Theology of the Old Testament, which he was awarded in 1968 after writing a thesis entitled The language of prophetic eschatology in the Old Testament. Whilst studying for his PhD, Wren was ordained into the Congregational Church (now the URC) and became the minister at Hockley and Hawkwell Congregational Church in Essex. His wife, Susan M. Heafield is a United Methodist pastor. When Wren left his church in 1970, he briefly served as the Consultant for Adult Education for the Churches’ Committee on World Development and the Coordinator of Third World First (now known as People and Planet). Between 1976 and 1983, he was a member of the Executive Board of the UK Aid Charity, after which he decided to return to ministry. In 2000, Wren became the Conant Professor of Worship at Columbia Theological Seminary, in Georgia, USA, eventually retiring in 2007. During this time, he was awarded an honorary Doctorate in Humane Letters from Christian Theological Seminary, Indianapolis. Wren’s hymns have been published in seven books and appear in almost every hymnal. His hymn Hidden Christ, Alive For Ever was the runner up in the international Millennium Hymn Competition awarded at St Paul’s Cathedral in 2000. Wren believes, “a hymn is a poem, and a poem is a visual art form. The act of reading a hymn aloud helps to recover its poetry and its power to move us—the power of language, image, metaphor, and faith-expression.” He explores this concept in his book Praying Twice: The Music and Words of Congregational Song. According to Wren, hymns should help people to “know and understand the meaning of God’s creating, self-disclosing and liberating activity centred and uniquely focused in Jesus Christ.” He was also determined to make hymns less male-orientated, removing words like “he” in order to make them more inclusive for women. Many churches have adopted this mindset as a result. Of Wren’s many hymns, these are the ones in our hymnbook:

2 Comments

Everyone knows the hymns All Things Bright and Beautiful and Once in Royal David’s City but how many people know about the woman who wrote them? Cecil Frances Alexander was born in Dublin in 1818 to Major John and Elizabeth Humphreys. She began writing verses at an early age and was later inspired by the Oxford Movement, which combined the Church of England with older teachings of the church to form Anglo-Catholicism. One member of the Oxford Movement, John Keble, later helped Alexander to edit her notable book Hymns for Little Children.

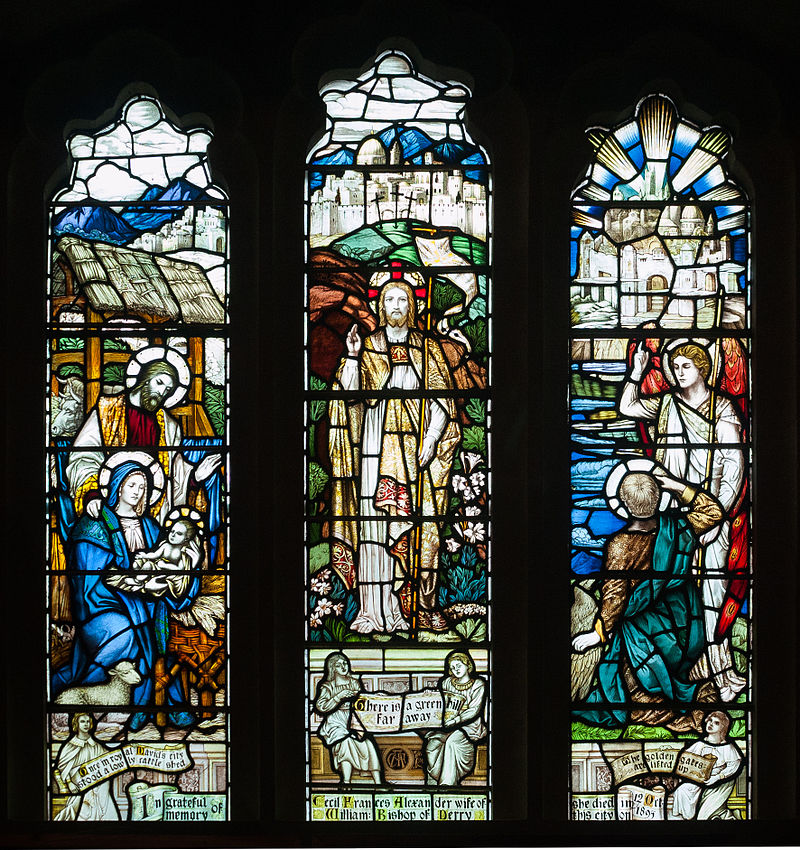

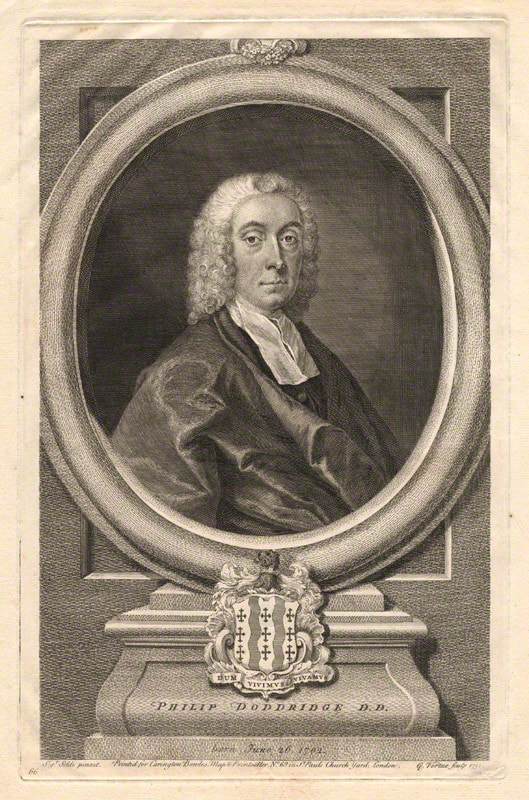

By 1840, Alexander’s hymns were well-known in the Church of Ireland. In 1850, she married the soon-to-be Bishop of Derry and Archbishop of Armagh, William Alexander. Their daughter, Eleanore Jane Alexander, inherited her mother’s gift for words and became a well-known poet. As a bishop’s wife, Alexander used the proceeds from her hymn books to help several charities. In the Diocese of Derry and Raphoe, her donations assisted in the founding of the Diocesan Institution for the Deaf and Dumb. She was also provided support at the Derry Home for Fallen Women and was an "indefatigable visitor to poor and sick". After her death in 1913, Alexander was commemorated with a stained glass window at St Columb’s Cathedral in Derry. Comprising of three windows, the memorial references three of her hymns: One in Royal, There is a Green Hill Far Away and The Golden Gates are Lifted Up. Many of Alexander’s hymns were targeted at children to help them learn the Apostle’s Creed. All Things Bright and Beautiful was based on the opening clause, “I believe in God, the Father Almighty, maker of heaven and earth.” Once in Royal David’s City, was inspired by the clause “I believe in Jesus Christ, our Lord, who was born of the Virgin Mary”. Originally intended to be sung in Sunday Schools, the hymn is now one of our most popular Christmas Carols. The hymn was put to music by Henry John Gauntlett and since 1919, the Kings College Chapel Cambridge has used the carol as their processional hymn at the Nine Lessons and Carols service. The Kings College Choir began the tradition that the first verse should be sung by a soloist and it was also the first song they recorded for public consumption in 1948. The phrase “Suffered under Pontius Pilate, was crucified, dead and buried,” inspired the hymn There is A Green Hill Far Away. Explaining Jesus’ death to young children has always been a challenge and Alexander wished to pen something that would make it easier. Inspired by a barren green hill near her home, Alexander used the hymn to explain that Jesus died so that we could be forgiven. Having written so many hymns, it is surprising that Cecil Frances Alexander is not better known. Unfortunately, she lived at a time when women were not considered as important as men, which has resulted in her name being glossed over. Nevertheless, her words live on. Jesus calls us, o'er the tumult is another of her well-known hymns. Philip Doddridge was a non-conformist minister and hymn-writer born in London in 1702, the youngest of twenty children. His maternal grandfather was the Rev. John Bauman, a Lutheran clergyman who had fled from Prague to escape from religious persecution.

Doddridge’s mother began to teach him about the Old and New Testament using the illustrated stories on their Dutch chimney tiles. Once he had learnt to read, he began studying the stories by himself in the Bible. Sadly, his mother died when he was eight and a year later he began attending the grammar school at Kingston-upon-Thames where Rev. Bauman had once been the headmaster. When his father died three years later, Doddridge was moved to a private school in St Albans where he was influenced by the teachings of Presbyterian minister Samuel Clark. Doddridge’s guardian stole his inheritance and abandoned him at the school. From then on, Clark took care of his as though he was his son. Many years later at Clark’s funeral, Doddridge said, "To him, under God, I owe even myself and all my opportunities of public usefulness in the church." After finishing school, instead of pursuing an Anglican ministry or law career as most of his peers did, Doddridge enrolled at the Dissenting Academy at Kibworth in Leicestershire. In 1727, he became the pastor at an independent congregation in Northhampton, although continued academic work into the 1740s. In 1730, he married Mercy Maris with whom he had nine children, four of whom survived to adulthood. Due to his academic connections, Doddridge influenced many religious thinkers and writers including Isaac Watts and John Wesley. He also established a youth scheme to encourage boys from poor families to study at a dissenting academy. On top of this, Doddridge wrote over 300 hymns, some which are still sung today. Doddridge suffered from poor health for most of his life and, in 1751, it took a turn for the worse. That year, he travelled to Lisbon but never returned, passing away from tuberculosis on 26th October 1751. Although he was buried in Lisbon, he is remembered in Northampton at Doddridge United Reformed Church, where he preached when it was a congregational church. Hymns by Doddridge that are in our hymn books include Awake, my soul, stretch every nerve; Father of Peace, and God of Love; Great God, We Sing That Mighty Hand; Hark, the Glad Sound! The Saviour Comes; My Gracious Lord, I Own Thy Right; O Happy Day, That Fixed My Choice; and Ye Humble Souls That Seek the Lord. Not much is known about the English hymn writer William Chatterton Dix but he is the author of a couple of well-known Christmas carols. Born in Bristol on 14th June 1837, Dix was named after the poet Thomas Chatterton who Dix’s father, John Dix, had written a biography. Dix was sent to Glasgow to develop a mercantile career, eventually becoming the manager of a maritime insurance company.

Alongside his career, Dix wrote hymns and carols. Most of his hymns have fallen out of favour, however, two of his carols remain popular favourites: As with Gladness Men of Old and What Child Is This? As with Gladness is an Epiphany hymn, which Dix wrote on 6th January 1859 whilst unwell in bed. Dix was frequently unwell and suffered a nearly fatal illness at the age of 29, followed by long bouts of depression. Suprisingly, he managed to live until the age of 61, dying on 9th September 1898 in Cheddar, Somerset. As with Gladness is based upon the visit of the magi in the Nativity. Using Matthew 2:1-12 as the theme, Dix’s carol describes the journey of the magi to visit Jesus, emphasising that it is not the gifts they bought that are important but their adoration of the Christ child. The first verse mentions the star that guided the magi (“Did the guiding star behold”) and the second describes the place of Jesus’ birth (“To that lowly manger bed”). The third verse mentions the gifts (“As they offered gifts most rare”) and the fourth references Jesus’ purpose (“Holy Jesus, every day/Keep us in the narrow way”). This is the only Epiphany hymn that does not use the words “magi” or “king” in the lyrics, nor does it allude to how many visited the child. What Child is This? was also written when Dix was unwell. In 1865, whilst recovering in bed, Dix underwent a spiritual renewal, which led to the composition of this carol that was subsequently set to the tune of Greensleeves. The carol was originally part of a longer poem called The Manger Throne but Dix only felt three of the stanzas were suitable for singing. The first verse begins with a rhetorical question, which is answered in the second verse. Subsequently, the second verse asks another question, which is answered in the third. Unlike As with Gladness, which focuses on the magi, What Child is This? is about the shepherd’s visit and the potential questions they may have had when they met him. Unfortunately, little else is known about William Chatterton Dix. Angels from the Realms of Glory is one of the best-known works of Scottish hymn-writer and poet James Montgomery. Similar to other writers in the 18th and 19th century, Montgomery was passionate about humanitarian causes such as the abolition of slavery. He was also concerned about the exploitation of child chimney sweeps.

Montgomery was born on 4th November 1771 in Irvine, North Ayrshire to a pastor and missionary of the Moravian Brethren. Montgomery followed in his father’s footsteps, training for ministry at a school near Leeds whilst his parents went to the West Indies as missionaries. Unfortunately, both Montgomery’s parents died abroad and he failed to complete his schooling. For a time, Montgomery was apprenticed to a baker in West Yorkshire followed by a storekeeper in the Dearne Valley, however, what Montgomery desired was a career in literature. In 1792, he moved to Sheffield to work as an auctioneer, bookseller and printer of the Sheffield Register. Later, he became the owner of the newspaper and renamed it the Sheffield Iris. For a time, it was the only newspaper published in Sheffield. Since school, Montgomery had written poems, however, they were soon getting him into trouble. In 1795, he was arrested for writing a poem about the fall of the Bastille and, in 1796, imprisoned again for his poem that criticised a magistrate. He kept himself amused in prison by continuing to write and published a pamphlet of poems known as Prison Amusements on his release. Despite enjoying poetry, Montgomery did not think any of them would become timeless classics. He believed the only way his name would be remembered was as a hymn writer. In some ways he was right and a handful of his hymns are still sung today. These include Angels from the Realms of Glory, Hail to the Lord's Anointed, Stand up and Bless the Lord and a version of The Lord is My Shepherd. Angels from the Realms of Glory, which is sung as a Christmas carol, was first published in the Sheffield Iris in 1816 and began to be sung in churches sometime after 1825. Montgomery’s success was boosted by the Reverend James Cotterill who preached at St Paul’s Chapel (now demolished), which was once part of Sheffield Cathedral. With Montgomery’s help, Cotterill republished his Selection of Psalms and Hymns Adapted to the Services of the Church of England with the addition of some of Montgomery’s hymns. It is estimated Montgomery wrote around 400 hymns, however, less than 100 are known today. On 30th April 1854, Montgomery passed away and was honoured by a public funeral. He had remained unmarried but was popular in the city for his religious lifestyle and philanthropy. Several streets in Sheffield were named after Montgomery, as was a pub and theatre. “A magnificent hymn of praise to God, perhaps the finest creation of its author, and of the first rank in its class,” is how Church of England clergyman John Julian described the hymn Praise to the Lord, the Almighty, the King of Creation. This was written in German by the German Reformed Church teacher Joachim Neander and translated into English by British writer Catherine Winkworth.

Joachim Neander, an important hymnist after the Reformation, was born in Bremen as Joachim Neumann in 1650. His grandfather, a musician, opted to change the family name to its Greek form Neander because Greek names were the current fashion. Neander’s father died when he was young and, therefore, he could not afford a prestigious education. Instead, he studied theology at a school in his hometown. At times, Neander felt he was wasting his time, however, after hearing a sermon by Protestant pastor Theodor Undereyk, he became much more serious about his studies. In 1671, a year after concluding his education, Neander became a private tutor in Heidelberg and, in 1674, a Latin teacher in Düsseldorf. Whilst teaching, Neander also gave sermons at gatherings and services in the area, which led him to become a pastor in his hometown of Bremen. He was a very popular pastor, however, died in 1680, a year after his appointment from tuberculosis at the age of 30. Most of Neander’s hymns were written in Düsseldorf, where, new evidence suggests, Neander caused a lot of problems with the Reformed Church. When Neander began working at the Latin School, which was run by the church, he got on amicably with the minister and elders. He accepted invitations to preach and visit the sick but soon tried to introduce new practices without permission, such as private prayer meetings. As the relationship between Neander and the Church began to crumble, Neander did even more to provoke the elders, for instance, refusing to attend Holy Communion because he did not want to sit in the same building as the “unconverted”. The final straw came when Neander made changes to the timetable and buildings at the school. Neander was subsequently suspended. All Neander’s hymns were written in German, however, those that have been translated into English include All my hope on God is founded and Praise to the Lord, the Almighty, the King of Creation. The latter, known as Lobe den Herren in German, was a favourite of King Frederick William III of Prussia, who first heard it in 1800. The composer, Johann Sebastian Bach, based his Chorale cantata, Praise the Lord, the mighty King of honour, on Neander’s words. The hymn paraphrases Psalm 103 (a.k.a Bless the Lord, O my soul) and Psalm 150 (Praise ye the Lord). There are at least ten English translations of Praise to the Lord, the Almighty, the King of Creation, but our modern version is based on the translation by Catherine Winkworth in 1863. Catherine Winkworth was born on 13th September 1827 in Holborn, London, to Henry Winkworth, a silk merchant. At the age of two, Winkworth moved with her family to Manchester where her father had a silk mill. Winkworth’s education was overseen by the Unitarian minister Reverend William Gaskell and a religious philosopher, Doctor James Martineau. The Winkworth family later moved to Bristol where she got a position as the secretary of the Clifton Association for Higher Education for Women. Winkworth was a feminist and is remembered at Clifton High School for Girls where a school house is named after her. Catherine Winkworth spent a year in Dresden where she developed a fascination of German hymnody. In 1854, she published the book Lyra Germanica, which consisted of a collection of German hymns that she had translated, including one by Joachim Neander. Unfortunately, Winkworth’s career as a translator was cut short when she died suddenly from heart disease whilst in Switzerland. She is commemorated on the liturgical calendar of the Episcopal Church with a feast day on 7th August, the same day as the hymn writer and priest John Mason Neale. "Arglwydd, arwain trwy'r anialwch,” wrote the Welsh premier hymnist William Williams (also known as Pantycelyn), which would eventually be known as Guide Me, O Thou Great Jehovah. Recorded as one of the greatest literary figures of Wales, Williams was among the leaders of the Welsh Methodist revival in the 18th-century.

William Williams was born on 11th February 1717 in the Welsh parish of Llanfair-ar-y-bryn to John and Dorothy Williams. The nickname Pantycelyn, which means “Holly Hollow”, comes from the name of the farmhouse where Williams died aged 73. Not much is known about Williams’ childhood other than he was brought up in a nonconformist household and attended a nonconformist college. He originally intended to study medicine but changed his mind after listening to the evangelical Methodist revivalist Howell Harris. Following this, he felt called to the priesthood and abandoned his nonconformist upbringing to take orders in the Establish Anglican Church. Williams’ first position was as curate to Theophilus Evans in the mid-Wales parish of Llanwrtyd. Whilst he was there, he became involved with the Methodist movement, which upset his parishioners who reported him to the Archdeacon. At the time, Methodism was not a church denomination but rather a faction, which many saw as a threat to the Anglican Church. Due to the complaints, Williams’ application to be ordained as a priest was refused. Since he could not be an Anglican priest, Williams opted to be a Methodist preacher instead. Williams began to travel throughout Wales to preach the doctrine of Calvinistic Methodism. Since his pay was poor, he supplemented his income by selling tea. As there were no Methodist churches, Williams preached his sermons in seiadau (fellowship meetings), which he had to personally organise as he went from place to place. Although there were several Methodist revivalists, Williams mostly worked alone, which was a considerable physical and mental burden, however, it was rewarding to see his community of converted Methodists grow. As well as being a leader of the Methodist Revival, Williams was a celebrated hymn writer. He became known as "Y pêr ganiedydd" (The Sweet Songster), which echoes the description of King David in 2 Samuel 23:1: “the sweet psalmist of Israel”. The majority of his hymns were written in Welsh apart from O’er the Gloomy Hills of Darkness, Hosannah to the Son of David and Gloria in Excelsis. Williams’ most famous, however, is the English translation of “Lord, lead thou through the wilderness”, which has been adapted into Guide Me, O Thou Great Jehovah/Redeemer. Cwm Rhondda, as it is sometimes known in Welsh, is based on Isaiah 58:11: “The Lord will guide you always; he will satisfy your needs in a sun-scorched land and will strengthen your frame. You will be like a well-watered garden, like a spring whose waters never fail.” The hymn, which was translated into English by Peter Williams (1722-96), describes the journey through the wilderness of God’s people after they escaped from slavery in Egypt. They were guided by a cloud by day and fire by night, eventually arriving in the land of Canaan after forty long years. God kept his people alive during the journey by supplying them with a daily portion of manna. Some people interpret Guide Me, O Thou Great Jehovah, as a Christian’s journey through life. By following Christ’s guidance, the Christian eventually reaches the gates of Heaven. The lyrics “verge of Jordan” can be understood as the gates and “death of death and hell’s destruction” as the end of time. As a result, the hymn is often sung at funerals, for instance, the funerals of Princess Diana and the Queen Mother. On the other hand, it was also sung at the royal weddings of Prince William and Catherine Middleton and Prince Harry and Meghan Markle. Non-Christian people may be familiar with the hymn from attending rugby union matches. Known as the “Welsh Rugby Hymn”, it is often sung by supporters of the Welsh team. Alternatively, the tune may be familiar to football fans, although, as of 2016, the lyrics have been changed to “You’re Not Singing Any More” and sung at the losing opposition! At 22 years of age, Robert Robinson wrote the words to the hymn Come Thou Fount of Every Blessing; words which are still familiar today. Robinson was an English dissenter who, as well as writing hymns, spent his life researching and studying the antiquity and history of Christian Baptism.

Robert Robinson was born on 27th September 1735 in Swaffham, Norfolk. His father, Michael Robinson, died when the boy was only five years old and his mother, Mary, was cut off from the rest of her family who disapproved of her “lowly marriage”. Fortunately, Robinson’s uncle paid for his position at a school near Scarning, Dereham, under the tuition of Reverend Joseph Brett. Robinson remained at school until the age of 14 when he was sent to London as an apprentice hairdresser. Inspired by his religious schooling and his love of reading, Robinson regularly studied the Bible and writings by early Christian authors. From his studies, Robinson became convinced infant baptism was inefficient, especially in comparison to the baptism of adults who have chosen to believe in God and the teachings of Jesus. As a result, none of Robinson’s twelve children were baptised as infants. In 1752, Robinson heard the Calvinist cleric George Whitefield preach and was inspired to convert to Evangelical Methodism. He was subsequently invited to assist at the Calvinistic Methodist Norwich Tabernacle set up by James Wheatley in 1754 but left after a matter of weeks. Rejecting Methodism, Robinson established a new Congregational church in St Paul’s Parish, Norwich. This, however, did not satisfy his beliefs and values, so by 1759, he had moved again. Robinson settled at the Stone-Yard Baptist Chapel in Cambridge, now known as St Andrew’s Street Baptist Church. He began preaching there as a Lecturer and then, in 1762, as a Pastor. Two years later, a new chapel was built to hold his growing congregation, which numbered more than one thousand. It was Robinson’s life-long wish to meet the Separatist theologian Joseph Priestley and finally got his chance in June 1790. Robinson travelled to Priestley’s New Meeting Chapel in Birmingham where he preached two sermons on Sunday 6thJune. Robinson planned to stay in Birmingham for a few days, however, he never left, dying in his sleep in the early hours of Wednesday 9th June 1790 at the age of 54. Priestley conducted his funeral and he was buried in the Dissenters' Burial Ground in Birmingham. Robinson’s two known hymns are Come Thou Fount of Every Blessing and Mighty God, while angels bless Thee, both of which remain in our hymnbooks today. The former was written shortly after Robinson converted to Methodism. The lyrics of Come Thou Fount… are based on 1 Samuel 7:12 in which Samuel says, “Thus far the Lord has helped us.” Samuel had placed a stone between Mizpah and Shen and named it Ebenezer, which means “stone of help”. Some versions of the song contain the reference to the stone in the second verse: Sorrowing I shall be in spirit, Till released from flesh and sin, Yet from what I do inherit, Here Thy praises I'll begin; Here I raise my Ebenezer; Here by Thy great help I’ve come; And I hope, by Thy good pleasure, Safely to arrive at home. “God moves in a mysterious way.” The English poet and hymnodist William Cowper coined this adage in his poem Light Shining out of Darkness in 1773. Now known as God Moves in a Mysterious Way, the poem is sung as a hymn in many Christian churches. Cowper was an associate of John Newton (see previous article) and wrote poems in support of the Abolitionist campaign. He also wrote several famous hymns.

Cowper was born in Berkhamsted, Hertfordshire on 26th November 1731. His father John was rector of the Church of St Peter and his mother, Ann, sadly passed away after giving birth to his younger brother. The death of Cowper’s mother greatly affected the young boy and she became the subject of his poem On the Receipt of My Mother’s Picture, which was written five decades later. Moving from school to school because of severe bullying, Cowper eventually settled at Westminster School in 1742. Here he made life long friends and enhanced his love of reading. Afterwards, Cowper began to train for a career in law at Ely Place, Holborn and hoped to settle down with his sweetheart Theodora. Unfortunately, Theodora’s father rejected the match and Cowper began to experience bouts of depression. In 1763, Cowper was offered a position as Clerk of Journals at the House of Lords but suffered a mental breakdown at the thought of the exams this required. After trying to commit suicide on more than one occasion, Cowper was admitted to an asylum in St. Albans. After his recovery, Cowper moved in with a retired clergyman in Huntingdon, Cambridgeshire. Reverend Morley Unwin and his wife Mary got on so well with Cowper that they invited him to move with them to Olney near Milton Keynes. It was in Olney where Cowper met John Newton who invited him to contribute to a hymnbook he was compiling. Known as the Olney Hymns, Cowper contributed several hymns, including the one now titled God Moves in a Mysterious Way. Written shortly before another bout of severe depression, the six verses encourage people to trust God’s greater wisdom in the face of trouble or uncertainty. In 1773, Cowper once again became mentally unwell. He believed he was eternally condemned to hell and hallucinated that God was commanding him to sacrifice his life. Mary Unwin, who Cowper was still living with despite her husband having passed away, took great care of him until he was well enough to focus on writing poetry again. Cowper and Mary Unwin moved to Weston Underwood in Buckinghamshire in 1786 where Cowper began a lengthy project, translating Homer’s Iliad and Odyssey into English. During this time, he met and befriended Dr John Johnson, a clergyman in Norfolk, who Cowper and Mary moved to be near in 1795. Unfortunately, Mary died the following year and Cowper relapsed into depression, which he never fully overcame. Dr Johnson looked after Cowper for the rest of his life. In 1800, Cowper was diagnosed with dropsy and died soon after. He is buried in the chapel of St Thomas of Canterbury in East Dereham and is honoured by a window in Westminster Abbey. Amongst Cowper’s many hymns are the following, which we either sing in our church or are at least recognisable:

Cowper is remembered mostly for his poems, particularly The Negro’s Complaint, written in 1788. Originally intended to be sung, the poem talks about slavery from the perspective of a slave. He was likely inspired by John Newton’s experience aboard a slave ship. The poem became popular during the civil rights movement of the 20th century and was often quoted by Martin Luther King Jr. “Amazing grace! (how sweet the sound)” is the first line of one of the most recognisable Christian hymns from the 18thcentury. John Newton, an English Anglican clergyman who began his career as a sailor in the Royal Navy, wrote this hymn and a few others, which we sing today.

John Newton was born on 4th August 1725 in Wapping to John Newton the Elder, a shipmaster, and Elizabeth. Sadly, his mother died of tuberculosis in 1723 and Newton was sent to boarding school. After two years, Newton moved into his father’s new home in Aveley, Essex, where he lived with his new wife. Newton experienced his first sea voyage at the age of eleven when he accompanied his father on his ship. John Newton the Elder intended his son to work on a sugar plantation in Jamaica, however, after enjoying a total of six voyages with his father, Newton signed on with a merchant ship sailing in the Mediterranean. Less than a year after he had started working, Newton was forced to join the Royal Navy where he became a midshipman aboard HMS Harwich. Newton tried to desert but was caught and flogged in front of the rest of the crew then demoted to a common seaman. He struggled mentally after this humiliation and eventually transferred to a ship called Pegasus, which was bound for West Africa. Unfortunately, life on this ship was no better. Pegasus was a slave ship that transported African slaves to North America. Newton did not get on with the crew and, in 1745, they left him with a slave dealer in West Africa. Newton was now a slave for Princess Peye of the Sherbro people who abused and mistreated him until 1748 when he was rescued by a sea captain who had been sent by Newton’s father to locate him. On the journey back to England, the ship was caught in a severe storm. Believing he would die, Newton prayed to God, asking for forgiveness, after which the storm abated. Following this, Newton began to read the Bible and, by the time the ship reached England, had converted to evangelical Christianity. He then married his childhood sweetheart Mary Catlett and adopted his two orphaned nieces, Elizabeth Cunningham and Eliza Catlett. Conversion to Christianity did not stop Newton’s activity within the slave trade. Between 1750 and 1754, Newton made three voyages as captain of a slave ship and only stopped when he suffered a severe stroke. In 1755, Newton worked as a tax collector, studying Greek, Hebrew and Syriac in his spare time. In 1757, Newton applied to be ordained as a priest in the Church of England but it was a long time before he was accepted. Finally, in 1764 he was ordained and became the curate of Olney in Buckinghamshire. In 1779, Newton was invited to become the Rector of St Mary Woolnoth, Lombard Street in the City of London. He remained in that position for the remainder of his life and offered advice to many young churchgoers who were struggling with their faith. One of these people was William Wilberforce, an MP who led the movement to abolish slavery. As an ally of Wilberforce, Newton helped to enact the Slave Trade Act of 1807. Newton published a pamphlet called Thoughts Upon the Slave Trade, which described the horrific conditions on the slave ships and publically apologised for his involvement. During Newton’s life in the Church, he wrote several hymns, some of which were published in Olney Hymns, a collaboration between Newton and fellow hymn writer William Cowper. Newton’s hymns include Glorious Things of Thee Are Spoken, based on Psalm 87:3 (“Glorious things are said of you, city of God.”), and How Sweet The Name of Jesus Sounds. Of course, his most famous is Faith's Review and Expectation, which is now known as Amazing Grace. Amazing Grace was written from Newton’s personal experience. He did not have a religious upbringing and his life’s path was full of twists and turns, however, he found his way to God, who forgave and redeemed him of his sins. Newton wrote the hymn to illustrate his sermon on New Year’s Day in 1773. His sermon was based on 1 Chronicles 17 in which the prophet Nathan tells David God will maintain his family line forever. Newton emphasised that God is involved in everyone’s lives even if they may not be aware. Newton described sinners as "blinded by the god of this world" until "mercy came to us not only undeserved but undesired ... our hearts endeavoured to shut him out till he overcame us by the power of his grace." The lyrics to Amazing Grace also contain references to the New Testament. “I once was lost, but now am found,” refers to the parable of the Prodigal Son and “Was blind, but now I see,” comes from the account of Jesus healing a blind man written in the Gospel of John. As well as writing hymns, Newton penned a few books, including an autobiography and Letters to a Wife, in which he expressed his grief after his wife died in 1790. Newton also wrote a preface to John Bunyan’s The Pilgrim’s Progress. Over a decade and a half after his wife’s death, John Newton passed away at the age of 82 on 21st December 1807. On his tomb at Olney, his self-penned epitaph reads “JOHN NEWTON. Clerk. Once an infidel and libertine a servant of slaves in Africa was by the rich mercy of our LORD and SAVIOUR JESUS CHRIST preserved, restored, pardoned and appointed to preach the faith he had long laboured to destroy. Near 16 years as Curate of this parish and 28 years as Rector of St. Mary Woolnoth.” Newton has been honoured with a stained-glass window at St Peter and Paul Church in Olney and, in 1982, Newton was inducted into the Gospel Music Hall of Fame. Newton’s influence on William Wilberforce was immortalised in the film Amazing Grace in which Albert Finney portrayed a penitent Newton, haunted by the ghosts of 20,000 slaves. |

©Copyright

We are happy for you to use any material found here, however, please acknowledge the source: www.gantshillurc.co.uk AuthorRev'd Martin Wheadon Archives

June 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed