|

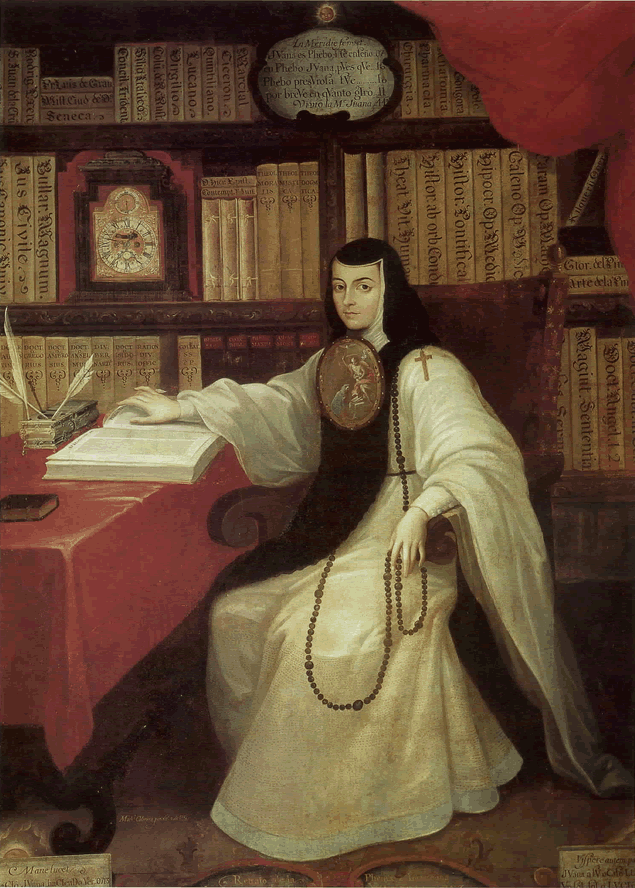

Juana Inés de Asbaje y Ramírez de Santillana was born on 12th November 1648 in the village of San Miguel Nepantla near Mexico City. Although she had older sisters, Juana was an illegitimate child because her parents never married. Her father, a Spanish captain called Pedro Manuel de Asbaje, abandoned the family shortly after Juana’s birth. Her mother was a Criolla woman called Isabel Ramírez. The Corillo people were Latin Americans with Spanish ancestors, which gave them more authority in Colonial Mexico, which belonged to the Spanish Empire. Juana’s father was Spanish, and her maternal grandparents were Spanish, thus making her a Criolla. Despite the lack of care from her biological father, Juana grew up in relative comfort on her maternal grandfather’s Hacienda, the Spanish equivalent of an estate. Her favourite place was the Hacienda chapel, where Juana hid with books stolen from her grandfather’s library. Girls were forbidden to read for leisure, but this did not prevent Juana from learning to read and write. At the age of three, Juana followed her sister to school and quickly learned how to read Latin. Allegedly, by the age of 5, Juana understood enough mathematics to write accounts, and at 8, wrote her first poem. By her teens, Juana knew enough to teach other children Latin and could also understand Nahuatl, an Aztec language spoken in central Mexico since the seventh century. It was unusual for those of Spanish descent to speak the native languages. The Spanish aimed to replace the Mexicano tongue with their Latin alphabet, so it was almost with defiance that Juana went out of her way to not only learn Nahuatl but compose poems in the language too. Juana finished school at 16 but wished to continue her studies at university. Unfortunately, only men could receive higher education. Juana spoke to her mother about her aspirations, suggesting she could disguise herself as a man to attend the university in Mexico City. Despite her pleading, Juana’s mother refused to allow her daughter to attempt such a risky plan. Instead, Isabel sent Juana to the colonial viceroy’s court to work as a lady-in-waiting. Under the guardianship of the viceroy’s wife, Leonor de Carreto (1616-73), Juana continued her studies in private. Yet, she could not keep her ambitions secret from her mistress, who informed the viceroy of Juana’s intelligence. Rather than reprimanding her, the viceroy Antonio Sebastián Álvarez de Toledo (1622-1715) took interest in Juana’s education. Wishing to test Juana’s intellect, the viceroy arranged a meeting of several theologians, philosophers, and poets and invited them to question the young girl. The men quizzed Juana on many topics, including science and literature, and she managed to impress them with her answers. They also admired how Juana conducted herself, and she remained unphased by the difficult questions they threw at her. News of the meeting spread throughout the viceregal court. No longer needing to hide her writing skills, Juana produced many poems and other writings that impressed all those who read them. Her literary accomplishments spread across the Kingdom of New Spain, which covered much of North America, northern parts of South America and several islands in the Pacific Ocean. Yet, female scholars and writers were an anomaly at the time, and rather than attract praise, Juana drew the attention of many suitors. After refusing many proposals of marriage, Juana felt desperate to escape from the domineering men. She wanted “to have no fixed occupation which might curtail [her] freedom to study.” The only safe place she could find where she could continue her work was the Monastery of St. Joseph, so she became a nun. Juana spent over a year with the Discalced Carmelite nuns as a postulant, then moved to the monastery of the Hieronymite nuns in 1669, preferring their more relaxed rules. The San Jerónimo Convent, which became Juana’s home for the rest of her life, was established in 1585 by Isabel de Barrios. Only four nuns lived in the building at first, but they soon grew in number, becoming one of the first convents of nuns of the Saint Jerome order. They based their role in life on the biblical scholar Saint Jerome (342-420), who translated most of the Bible into Latin. Known for his religious teachings, Jerome favoured women and identified how a woman devoted to Jesus should live her life. During his lifetime, Jerome knew many women who had taken a vow of virginity. He advised them on the clothing they should wear, how to conduct themselves in public, and what and how they should eat and drink. Despite taking on the title “Sor”, the Spanish equivalent of sister, Sor Juana’s main aim was to focus on her literary pursuits. Whilst she followed the ways of the Hieronymite nuns, she spent all her spare time writing. Juana’s previous employers, the Viceroy and Vicereine of New Spain became her patrons, helping her publish her work in colonial Mexico and Spain. Sor Juana also received support from the intellectual Don Carlos de Sigüenza y Góngora (1645-1700), who shared her religious beliefs as well as her passion for literature. Sigüenza, who claimed, “There is no pen that can rise to the eminence … of Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz,” also encouraged Juana to explore scientific topics. Sor Juana dedicated some of her works, particularly her poems, to her patrons. Those written for Vicereine Leonor de Carreto often featured the name Laura, a codename assigned by Juana. Another patron, Marchioness Maria Luisa Manrique de Lara y Gonzaga (1649-1721) was “Lysi”. Juana also wrote a comic play called Los empeños de una casa (House of Desires) for Doña Maria Luisa and her husband in celebration of the birthday of their first child, José. The first performance of Los empeños de una casa took place on 4th October 1683 and contains three songs in praise of Doña María Luisa Manrique: “Divine Lysi, Let Pass“, “Beautiful María” and “Tender Beautiful Flower Bud”. The protagonist, Doña Ana of Arellano, resembles the marchioness, who Sor Juana held in high regard. The play features two couples who are in love but cannot be together. Mistaken identities cause the characters much distress and the audience much hilarity. By the end of the final scene, everyone pairs up with the right partner, except one man who remains single as a punishment for causing the initial deception. In terms of theme and drama, Los empeños de una casa is a prime example of Mexican baroque theatre. Another play by Sor Juana premiered on 11th February 1689 to mark the inauguration of the viceroyalty Gaspar de la Cerda y Mendoza (1653-97). Sor Juana based Love is but a Labyrinth on the Greek mythological story of Theseus and the Minotaur. Theseus, the king and founder of Athens, fights against the half-bull, half-human Minotaur to save the Cretan princess Ariadne. Although Theseus resembled the archetypal baroque hero, Sor Juana portrayed him as a humble man rather than proud. Not all of Sor Juana’s writings were intended for public consumption. In 1690, Manuel Fernández de Santa Cruz (1637-99), the Bishop of Puebla, published Sor Juana’s critique of a sermon by the Jesuit priest Father António Vieira (1608-97). Titled Carta Atenagórica (Athenagorical Letter or a letter “worthy of Athena’s wisdom”), Juana expressed her dislike of the colonial system and her belief that religious doctrines are the product of human interpretation. She criticised Father António Vieira for his dramatic and philosophical representation of theological topics. Most importantly, Juana called the priest out for his anti-feminist attitude. Alongside Sor Juana’s critique, the Bishop of Puebla published a letter under the pseudonym Sor Filotea de la Cruz, in which he admonished the nun for her opinions. Ironically, the bishop agreed with many of Sor Juana’s thoughts, but he ended the letter by saying Sor Juana should concentrate on religious rather than secular studies. Whilst the critique focused on a religious sermon, Sor Juana included colonialism and politics in her argument, which the bishop felt were inappropriate topics for a woman, let alone a nun. Sor Juana responded to Sor Filotea, the Bishop of Puebla, in which she defended women’s rights to education and further study. Whilst she agreed that women should not neglect their duties, in her case her obedience to the Church and God, Juana pointed out that “One can perfectly well philosophise while cooking supper.” By this, she meant women could balance their education and everyday tasks. She jokingly followed this with the quip, “If Aristotle had cooked, much more would have been written.” In her response, Sor Juana quoted the Spanish nun St Teresa of Ávila (1515-82) as well as St Jerome and St Paul to back up her argument that “human arts and sciences” are necessary to understand sacred theology. She suggested if women were elected to positions of authority, they could educate other women, thus alleviating a male tutor’s fears of being in intimate settings with female students. The nun’s controversial response caused a lot of concern amongst high-ranking (male) officials who criticised her “waywardness”. They were angry with Sor Juana for challenging the patriarchal structure of the Catholic Church, and for claiming her writing was as good as historical and biblical texts. As a result, the San Jerónimo Convent forbid Juana from reading and sold her collection of over 4,000 books and scientific instruments for charity. With no one on her side, Sor Juana relented and agreed to renew her vows. The convent also required Juana to undergo penance, but rather than signing the penitential documents with her name, she wrote: “Yo, la Peor de Todas” (I, the worst of all women). From 1693 onwards, Sor Juana focused solely on her religious orders. Never again did she pick up a pen to write or a book to read. Instead, Juana spent her time either in prayer or tending the sick, which led to fatal consequences. After nursing other nuns stricken during a plague, Sor Juana fell ill and passed away on 17th April 1695. To read the full article, click here This blog post was published with the permission of the author, Hazel Stainer. www.hazelstainer.wordpress.com

0 Comments

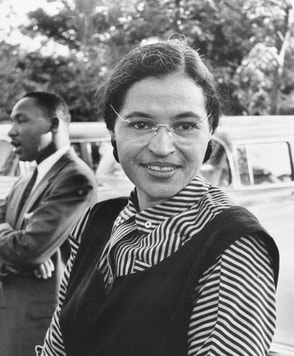

Many people know Rosa Parks as the black girl who refused to give up her seat to a white person on a bus. Even Doctor Who portrayed the story in a recent episode, but how many people know Rosa’s background? How many people know more about her than the bus incident? She is a recognisable name in the Civil Rights Movement, but is that all - just a name?

Born Rosa Louise McCauley on 4th February 1913, Rosa grew up in Tuskegee, Alabama, until her parents, Leona and James, separated. Rosa moved to Montgomery with her mother and younger brother Sylvester, where she lived on her grandparents' farm and attended the African Methodist Episcopal Church. Rosa’s mother taught her how to sew, and by the age of ten, Rosa completed her first quilt. She continued to sew while studying academic courses at the Montgomery Industrial School for Girls, making herself dresses to wear. Although Rosa enrolled at a high school set up by the Alabama State Teachers College for Negroes, she dropped out when her grandmother became unwell. In 1932, Rosa married the barber Raymond Parks, who belonged to the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP). Rosa took on jobs as a domestic worker, but her husband encouraged her to complete her high school education, which she achieved in 1933. A decade later, Rosa joined the NAACP, becoming its first female secretary. For some time, she was also the only female member. As part of her role, Rosa investigated false rape claims against black men and the gang-rape of Recy Taylor (1919-2017), a black woman from Abbeville, Alabama. The Chicago Defender called the resulting campaign concerning the latter "the strongest campaign for equal justice to be seen in a decade." Rosa experienced “integrated life” while briefly working for the Maxwell Air Force Base, which did not condone racial segregation. This made her realise the extent of the differences between the lives of blacks and whites. Rosa also worked as a domestic and seamstress for Clifford (1899-1975) and Virginia Durr (1903-99), a white couple who encouraged and sponsored her attendance at the Highlander Folk School to learn more about civil rights in 1955. To travel to and from work and school, Rosa used public buses, which since 1900 had specific seating areas for blacks and whites. The front four rows were for whites only, and blacks were encouraged to sit at the far end of the bus. Over 75% of passengers were black, which made the rear of the bus very crowded. Blacks also had to use the back door of the bus, but on one occasion it was too crowded for Rosa, so she used the front entrance instead. After paying, the driver insisted she leave the bus and enter through the back door. As soon as Rosa had stepped out of the bus, the driver sped away. Rosa avoided that bus driver until 1955 after a long day at work. She did everything right: she entered the bus through the back door and sat in the first row of seats designated for black people. During the journey, crowds of people entered the bus, meaning many people had to stand, including white people. Seeing this, the driver asked those in the first row of black seats to stand up so the whites could sit. Whilst three blacks got up and moved, Rosa remained seated. The driver demanded her to move, and when she did not, he called the police. The police arrested Rosa and charged her with a violation of Chapter 6, Section 11 segregation law of the Montgomery City code. The NAACP bailed her out of prison that evening. “People always say that I didn't give up my seat because I was tired, but that isn't true. I was not tired physically, or no more tired than I usually was at the end of a working day. I was not old, although some people have an image of me as being old then. I was forty-two. No, the only tired I was, was tired of giving in.” - Rosa Parks, Rosa Parks: My Story, 1992 Rosa Parks was not the first person to refuse to give up her seat, but her actions inspired the NAACP to organise a bus boycott. On 5th December 1955, the day of Rosa’s trial, campaigners distributed 35,000 leaflets saying: “We are ... asking every Negro to stay off the buses Monday in protest of the arrest and trial ... You can afford to stay out of school for one day. If you work, take a cab, or walk. But please, children and grown-ups, don't ride the bus at all on Monday. Please stay off the buses Monday.” That day, over 40,000 black people walked to work instead of getting the bus. Some had to walk more than 20 miles through the driving rain. As Rosa’s trial continued, so did the bus boycott. For 381 days, black people in Montgomery avoided using the bus. Since they made up at least 75% of commuters, the bus companies suffered from a loss of bus fares, forcing the city to repeal its law about segregation on public transport. Rosa did not wish to take credit for this success, and Martin Luther King Jr agreed that Rosa was not the cause of the boycott but the catalyst: "The cause lay deep in the record of similar injustices." Although Rosa became an icon of the Civil Rights Movement, she suffered as a result. She received many death threats, disagreed with King’s approaches, and both she and her husband lost their jobs, prompting them to move to Hampton in Virginia in search of work. Rosa found a position as a hostess but soon moved to live with her brother in Detroit, Michigan. Her brother believed the discrimination against blacks to be less severe in the northern states, but Rosa failed to see any improvements. When African American John Conyers (1929-2019) stood for Congress, Rosa gave him her full support and convinced King to do the same. After Conyers' election, he hired Rosa as his secretary and receptionist, a position she kept until she retired in 1988. She visited schools, hospitals and facilities with and on Conyers’ behalf, plus attended Civil Rights marches across the country. During this time she became an ally of Malcolm X. She later took part in the black power movement. Rosa continued to support the Civil Rights Movement in various ways, although she never took up a leading position. During the 1970s, she helped to organise the freedom of several prisoners whose actions of self-defence had landed them in police custody. Unfortunately, Rosa could not contribute much later that decade due to the poor health of her family, although she donated what little money she could to the cause. In 1977, both her husband and brother passed away from cancer. Following these losses, she broke two bones after slipping on an icy pavement, prompting her to move in with her elderly mother in an apartment for senior citizens. Her mother passed away in 1979 aged 92. With renewed vigour, Rosa returned to the Civil Rights scene, co-founding the Rosa L. Parks Scholarship Foundation to provide scholarships for college students. When asked to speak at various organisations, Rosa usually donated her speaking fee to her scholarship foundation. Later, she established the Rosa and Raymond Parks Institute for Self Development, which aimed to "educate and motivate youth and adults, particularly African American persons, for self and community betterment.” In her later years, Rosa faced several challenges. At 81, a man broke into her house and demanded money. When she refused, he attacked her, landing her in hospital with facial injuries. Naturally, Rosa suffered severe anxiety after the attack and moved to a secure complex. Whilst she felt safe there, her fragile mind made it difficult for her to manage her finances. In 2002, she received an eviction notice due to lack of rent payment. When members of the public found out, the Hartford Memorial Baptist Church in Detroit raised funds to pay the rent on her behalf, allowing her to remain in her home for the remainder of her life. Rosa Parks passed away at age 92 on 24th October 2005. Before her funeral, a bus, similar to the one on which she refused to stand, drove her casket to the US Capitol in Washington DC where she became the first non-government official to lie in honour in the rotunda. At her memorial service, the United States Secretary of State Condoleezza Rice (b.1954) said she believed that if it had not been for Rosa Parks, she would not be Secretary of State today. At her death, Rosa left an extensive list of legacies, which continues to grow. Long before she passed away, places were named in her honour, such as Rosa Parks Boulevard in Detroit, and she received many medals and awards: Martin Luther King Jr. Award (1980), Presidential Medal of Freedom (1996), Congressional Gold Medal (1999), and several honorary doctorates. Since her death, the Rosa Parks Transit Center has opened in Detroit; Michigan renamed a plaza Rosa Parks Circle; the asteroid 284996 Rosaparks was named in her memory; and the Rosa Parks Railway Station opened in Paris. Americans also remember Rosa Parks with a statue in Montgomery, unveiled in 2019. Madam C.J. Walker was the first female self-made millionaire in America; she was also the first black female millionaire. Despite racism being rife in the country, Madam C.J. built an empire from nothing, developing a line of hair and beauty products for black women. She is also remembered for being a civil rights activist

Born on 23rd December 1867 in Louisiana to Owen and Minerva Breedlove, Madam C.J. was originally known as Sarah. She had one sister and four brothers, the elder of whom were born into slavery. Sarah was the first Breedlove child to be born into freedom after the Emancipation Proclamation was signed in 1862. Sadly, her mother passed away from cholera in 1872 and her father died the following year. From the age of ten, Sarah was brought up in Mississippi by her much older sister Louvenia and her brother-in-law, Jesse Powell. Around the same time, Sarah began working as a domestic servant. As an orphan, she had no time or money to go to school and the only education she received was at Sunday school before the death of her parents. Sarah had a rough time living with Louvenia. Jesse was an abusive man and Sarah took the first opportunity to escape from the household: getting married. Sarah was only 14 years old when she married Moses McWilliams in 1882. Three years later, Sarah gave birth to a daughter, A’Lelia (1885-1931), but in 1887, their lives were shattered by the death of Moses. To earn money, Sarah moved to St Louis, Missouri where her brothers lived to work as a laundress. She was determined to earn enough money to send her daughter to school, which was a difficult task earning less than $1 a day. Sarah also wanted to live an educated life and was jealous of the educated women at the African Methodist Episcopal Church she attended. In 1894, Sarah married John Davis, but their marriage was not a happy one and she left him in 1903. Meanwhile, Sarah was battling with severe dandruff, leading to baldness, which was a common problem for black women at the time. Hair products were made for white-skinned customers and were unsuitable for African-Americans. Sarah knew a little about haircare from her brothers who were barbers, but she was determined to do something about the quality of products available for black women. In 1904, she became an agent for Annie Malone (1877-1957), a black inventor and businesswoman who specialised in cosmetics. Using the knowledge she gained working for Malone, Sarah began to develop her own products, meanwhile, she continued to work for Malone in Denver, Colorado where she had moved in 1905. When Malone found out about Sarah’s products, she accused her of stealing the formula, despite it having been around for centuries. From then on, Sarah and Malone were rivals. In 1906, Sarah married a newspaper advertising salesman, Charles Joseph Walker (d.1926), and took on his name. Soon she was known as Madam C.J. Walker, a name which she marketed her products under. To begin with, Sarah sold her products door-to-door whilst her husband began to arrange advertising and promotion. When business improved, A'Lelia became involved with the business, setting up a mail-order operation in their home. Charles and Sarah travelled to the southern states to promote the business, eventually moving to Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, to set up a beauty parlour and training college. A’Lelia joined Madam C.J. in Pittsburgh in 1907 and persuaded her mother to open a beauty salon and office in New York. In 1910, Madam C.J. relocated to Indianapolis where she established the headquarters for the Madam C. J. Walker Manufacturing Company and began hiring staff to help with the management. Despite competition, Madam C.J.’s products were popular because they helped hair to regrow and prevented them from becoming brittle. Between 1911 and 1919, she employed thousands of women and trained over 20,000 people. Unfortunately, Charles and Sarah divorced in 1912, meaning she lost her business partner. As well as training her staff in haircare, she taught black women how to build their own business and become financially independent. In 1917, she established the National Beauty Culturists and Benevolent Association of Madam C. J. Walker Agents, which welcomed 200 people to its first annual conference. This was also the first-ever conference for businesswomen in the USA. "I am a woman who came from the cotton fields of the South. From there, I was promoted to the washtub. From there, I was promoted to the cook kitchen. And from there, I promoted myself into the business of manufacturing hair goods and preparations. I have built my own factory on my own ground." This is what Madam C.J. told the National Negro Business League (NNBL) when she spoke at one of their meetings in 1912. As well as concentrating on her business, Madam C.J. involved herself in many good causes, wishing to put her well-earned money to good use. Madam C.J. helped to raise funds for the YMCA and donated money to various churches and schools. She also became a patron of the arts and became friends with notable people, such as the author, Booker T. Washington (1856-1915), and civil rights activist, W.E.B. Du Bois (1868-1963). In 1917, she joined the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) and the following year the National Association of Colored Women's Clubs (NACWC), making sizable monetary donations to both. Around this time, Madam C.J. began to suffer from kidney failure and hypertension, passing away on 25th May 1919 at the age of 51. At her death, she was estimated to be worth almost one million dollars, making her the wealthiest African-American woman in the country. Her daughter took over the company as its president, which continued to operate until 1981. Madam C.J. Walker has been honoured several times since her death, including in recent years. Her company’s building in Indianapolis has been designated a National Historic Landmark, which now houses the Madam Walker Legacy Centre. In 2006, American actress and playwright Regina Taylor wrote The Dreams of Sarah Breedlove about Madam C.J.’s journey from rags to riches. Her most recent honour occurred in 2016 when the French beauty company Sephora launched a line of hair products called "Madam C. J. Walker Beauty Culture", which are suitable for many different hair types. Not only did Madam C.J. Walker create a successful business at a time when black people were struggling for equality, but she also improved the lives of thousands of others. Thanks to her, black women were able to start their own business thus helping them to escape from poverty and oppression. Madam C.J. was also a huge inspiration for future hair care and cosmetic businesses and will continue to be looked up to in years to come. Maya Angelou was one of the most influential black poets of the 20th and early 21st century, writing on themes of racism, identity, family and travel. She was also a civil rights activist and worked with both Martin Luther King Junior and Malcolm X. She was showered with awards and over 50 honorary degrees, however, her life was not always plain sailing.

Born Marguerite Annie Johnson on 4th April 1928 in Missouri to Bailey and Vivian Johnson, Maya was given her nickname from her older brother, Bailey Jr. Unfortunately, her parents’ marriage was not a happy one and they separated when she was three years old. Rather than take responsibility for his children, her father sent them to Arkansas to live with their grandmother, Annie Henderson. They remained there until Maya was seven when they moved home to live with their mother. Sadly, living with their mother also meant living with their mother’s abusive boyfriend who raped Maya when she was only eight years old. The man was arrested and locked up for one day but was murdered four days later, most likely by Maya’s uncles. The abuse greatly affected Maya who became mute for five years, even after moving back in with her grandmother. Fortunately, her school teacher helped Maya to regain her voice whilst also feeding her passion for reading, introducing the young girl to authors who would influence her future career. When Maya was 14, she rejoined her mother, who was then living in California. At the age of 16, she became the first black female cable car conductor in San Francisco, where she worked whilst also attending school. Unfortunately, she got herself in trouble and, no more than three weeks after graduation, gave first to a baby boy, Clyde. In 1951, Maya married a Greek electrician called Tosh Angelos, despite her mother’s disapproval. At that time, interracial marriages were unusual. Maya began taking dance lessons and dreamt of a career in a dance team. In an attempt to increase her prospects, Maya, Tosh and Clyde moved to New York for a year where she studied African dance. For reasons unknown, in 1954, not long after returning to San Francisco, Maya’s marriage ended. Having to fend for herself financially, Maya began dancing in local clubs, such as The Purple Onion, under her professional name, Maya Angelou. In 1954-5, she toured Europe by acting in the opera Porgy and Bess and, in 1957, wrote and recorded an album called Miss Calypso. In every country she visited, Maya made a point of learning the language, quickly becoming proficiently multilingual. In 1959, African-American author John Oliver Killens encouraged Maya to focus more on writing songs and poems rather than solely performing. She joined the Harlem Writers Guild and soon became a published author. The following year, she met Martin Luther King Jr and was inspired to organise a concert for the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC) called Cabaret for Freedom. Maya had a brief relationship with South African freedom fighter Vusumzi Make and moved with him to Cairo in 1961 along with her son who had renamed himself Guy. The relationship only lasted a year, after which Maya moved to Ghana where her son enrolled at university. While Guy was studying, Maya worked as a freelance writer for The African Review and Radio Ghana. Whilst living in Ghana, Maya met Malcolm X who was touring Africa. He encouraged her to return to the USA in 1965 and help him set up the Organization of Afro-American Unity. Shortly after, Malcolm X was assassinated and Maya, at a loss, moved to Hawaii where her brother lived and refocused on her singing career. Not long after, she returned to Los Angeles to resume her writing career. In 1968, Martin Luther King Jr approached Maya for help in organising a march. Tragically, in a similar fate to Malcolm X, King was then assassinated on what was Maya’s 40th birthday. After a bout of depression, Maya resumed writing and published her first autobiography, I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings. Initially, the publishers were unsure whether to publish the book but it went on to become a bestseller, earning Maya international recognition. In 1972, Maya became the first black woman to write a screenplay, which was filmed in Sweden and released under the name Georgia, Georgia. She also wrote the soundtrack for the film. The following year, she married the Welsh carpenter Paul du Feu who had once been married to the radical feminist, Germaine Greer. For the next decade, Maya continued to write articles, screenplays, poems and books and also became close friends with Oprah Winfrey. Unfortunately, her second marriage ended in divorce in 1981. Returning to the southern states, Maya accepted the lifetime Reynolds Professorship of American Studies at Wake Forest University in North Carolina, becoming one of the first black women to be a full-time professor. She taught on a variety of themes that interested her, including philosophy, ethics, writing and theatre, but also continued to write. In 1993, Maya Angelou recited one of her poems at the inauguration of Bill Clinton - the first poet to do so since John F. Kennedy’s inauguration. This televised event increased her fame across the world and earned her a Grammy Award. In 1996, she finally achieved her goal of directing a film (Down in the Delta) and, by 2002, she had published her 6th autobiography. Hillary Clinton, during her campaign for the Democratic Party 2008 presidential primaries, used Maya Angelou’s endorsement on her advertisements. After Obama won the primary, Maya gave him her full support. When Obama became the first African-American president, Maya was quoted saying, "We are growing up beyond the idiocies of racism and sexism." Maya published her 7th and final autobiography in 2013 called Mom & Me & Mom, focusing on her relationship with her mother. The following year, on 28th May 2014, passed away after her health deteriorated. Despite cancelling a few events, Maya Angelou was working and attending events right up until her death. Tributes flooded in as soon as the news was made public and her first biography instantly became the number one bestseller on Amazon. A public funeral was held at Mount Zion Baptist Church in Winston-Salem, North Carolina, where she had been a member for 30 years. As well as the Grammy Award for her poetry recital at Clinton’s inauguration, Maya Angelou received several awards, including a Pulitzer Prize, Tony Award, two more Grammys, the Presidential Medal of Freedom and over 50 honorary degrees. Although these were awarded for her talents, they are also a sign that she overcame her past, the abuse and did not let racial inequalities stand in the way of her success. Saint Hildegard of Bingen (1098-1179), also known as the Sybil of the Rhine, was a Benedictine abbess, composer, Christian mystic and the founder of scientific natural history in Germany. There are more surviving songs or “chants” by Hildegard than any other composer from the Middle Ages. She is also one of the few composers to write both the music and the lyrics.

The exact date of Hildegard’s birth is unknown but it has been estimated as during the year 1098. She is believed to have been the tenth and youngest child of Mechtild of Merxheim-Nahet and Hildebert of Bermersheim, who worked for the Count Meinhard of Sponheim in the Holy Roman Empire. From the age of three, Hildegard claimed to have experienced visions, which led her parents to offer her as an oblate to the Benedictine Disibodenberg Monastery in the Palatinate Forest, south Germany, where she took her vows in 1112. She described her visions as "the reflection of the living Light” and explained she experienced revelations in her soul through the five senses. In 1136, Hildegard was elected Magistra (superior) by the other nuns. The Abbot of Disibodenberg wished to make her the Prioress, however, she refused and requested she and her fellow nuns to Rupertsberg, near the River Rhine. Her request was denied but after falling ill and believing it to be God’s doing, Hildegard was granted money to set up St. Rupertsberg monastery in 1150. In 1165, she set up a second monastery in the nearby town of Eibingen. Hildegard was initially hesitant to share her visions with the other nuns and ignored the voice that told her to "write down that which you see and hear." When she was 42 years old, she fell physically ill and, while she suffered, heard the voice say, “Cry out, therefore, and write thus!” So, she did as she was told and wrote down every vision she received thereafter. When Pope Eugene III (1080-1153) learnt of Hildegard’s writings, he granted her Papal approval, which meant her visions were accepted as truth by the Roman Catholic Church. In total, Hildegard wrote three volumes of visionary theology: Scivias, Liber Vitae Meritorum and Liber Divinorum Operum. She also penned over 400 letters and a variety of musical compositions. Ordo Virtutum (Play of the Virtues), is a morality play containing 82 songs that are believed to have been written by Hildegard. In addition to this, there are at least 69 musical compositions under her name. Most of her songs resemble a chant and lack tempo and rhythm, which may be why they were forgotten until rediscovered in recent decades. Although Hildegard’s songs are not sung today, they have inspired many contemporary composers and writers, such as David Lynch and Gordon Hamilton. Within her works, Hildegard writes of life in the monasteries as well as her visions. Working in the herb garden and reading in the library led her to gain practical skills in diagnosis, treatment and “spiritual healing”. She maintained plants and stones were put on Earth for human use as recorded in the Book of Genesis, therefore, it was only right she learnt about their properties. These studies resulted in two volumes of work, Physica, in which Hildegard explained the medicinal properties of plants, stones, fish and animals, and Causae et Curae, which explored the human body and the causes and treatments of diseases. Although Hildegard was not a trained physician or scientist, her insight into the natural world made her one of, if not the first person to study scientific natural history in Germany. Hildegard often wrote in code, using an alphabet she had invented, which goes to show the complexity of her thoughts and mental abilities. During her lifetime, she acted on her own authorisation as a theologian, travelling around Germany on preaching tours. Not only was she speaking and writing of ideas beyond many people’s comprehension at the time, but she was also conducting work above her station as a woman. Hildegard was an early feminist and wrote in one of her books, "woman may be made from man, but no man can be made without a woman." On 17th September 1179, Hildegard died. Allegedly, at the moment of her death, two streams of light appeared in the sky, intersecting above the room in which she lay. Hildegard was one of the first people whose name was put forward to be canonised, however, she was never officially made a saint. Nonetheless, people began referring to her as Saint Hildegard, including several popes and she was assigned 17th September, the date of her death, as her Saint Day. In 2012, Pope Benedict XVI named her a Doctor of the Church, making her the fourth woman to receive the honour. The other three women are St Teresa of Ávila, St Catherine of Siena and St Thérèse of Lisieux. Everyone knows the hymns All Things Bright and Beautiful and Once in Royal David’s City but how many people know about the woman who wrote them? Cecil Frances Alexander was born in Dublin in 1818 to Major John and Elizabeth Humphreys. She began writing verses at an early age and was later inspired by the Oxford Movement, which combined the Church of England with older teachings of the church to form Anglo-Catholicism. One member of the Oxford Movement, John Keble, later helped Alexander to edit her notable book Hymns for Little Children.

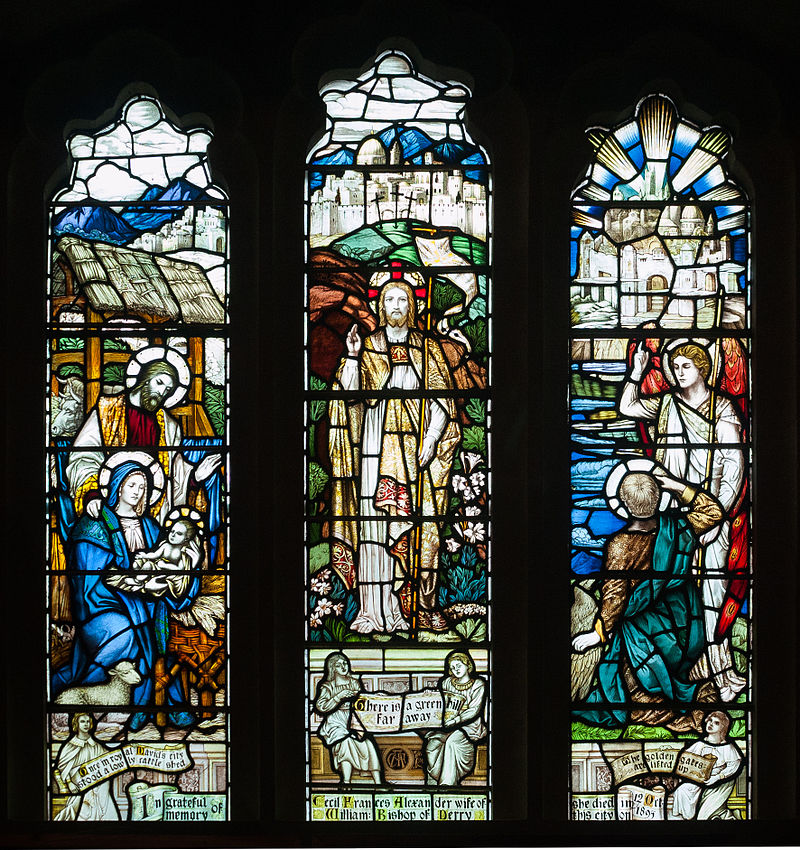

By 1840, Alexander’s hymns were well-known in the Church of Ireland. In 1850, she married the soon-to-be Bishop of Derry and Archbishop of Armagh, William Alexander. Their daughter, Eleanore Jane Alexander, inherited her mother’s gift for words and became a well-known poet. As a bishop’s wife, Alexander used the proceeds from her hymn books to help several charities. In the Diocese of Derry and Raphoe, her donations assisted in the founding of the Diocesan Institution for the Deaf and Dumb. She was also provided support at the Derry Home for Fallen Women and was an "indefatigable visitor to poor and sick". After her death in 1913, Alexander was commemorated with a stained glass window at St Columb’s Cathedral in Derry. Comprising of three windows, the memorial references three of her hymns: One in Royal, There is a Green Hill Far Away and The Golden Gates are Lifted Up. Many of Alexander’s hymns were targeted at children to help them learn the Apostle’s Creed. All Things Bright and Beautiful was based on the opening clause, “I believe in God, the Father Almighty, maker of heaven and earth.” Once in Royal David’s City, was inspired by the clause “I believe in Jesus Christ, our Lord, who was born of the Virgin Mary”. Originally intended to be sung in Sunday Schools, the hymn is now one of our most popular Christmas Carols. The hymn was put to music by Henry John Gauntlett and since 1919, the Kings College Chapel Cambridge has used the carol as their processional hymn at the Nine Lessons and Carols service. The Kings College Choir began the tradition that the first verse should be sung by a soloist and it was also the first song they recorded for public consumption in 1948. The phrase “Suffered under Pontius Pilate, was crucified, dead and buried,” inspired the hymn There is A Green Hill Far Away. Explaining Jesus’ death to young children has always been a challenge and Alexander wished to pen something that would make it easier. Inspired by a barren green hill near her home, Alexander used the hymn to explain that Jesus died so that we could be forgiven. Having written so many hymns, it is surprising that Cecil Frances Alexander is not better known. Unfortunately, she lived at a time when women were not considered as important as men, which has resulted in her name being glossed over. Nevertheless, her words live on. Jesus calls us, o'er the tumult is another of her well-known hymns. “A magnificent hymn of praise to God, perhaps the finest creation of its author, and of the first rank in its class,” is how Church of England clergyman John Julian described the hymn Praise to the Lord, the Almighty, the King of Creation. This was written in German by the German Reformed Church teacher Joachim Neander and translated into English by British writer Catherine Winkworth.

Joachim Neander, an important hymnist after the Reformation, was born in Bremen as Joachim Neumann in 1650. His grandfather, a musician, opted to change the family name to its Greek form Neander because Greek names were the current fashion. Neander’s father died when he was young and, therefore, he could not afford a prestigious education. Instead, he studied theology at a school in his hometown. At times, Neander felt he was wasting his time, however, after hearing a sermon by Protestant pastor Theodor Undereyk, he became much more serious about his studies. In 1671, a year after concluding his education, Neander became a private tutor in Heidelberg and, in 1674, a Latin teacher in Düsseldorf. Whilst teaching, Neander also gave sermons at gatherings and services in the area, which led him to become a pastor in his hometown of Bremen. He was a very popular pastor, however, died in 1680, a year after his appointment from tuberculosis at the age of 30. Most of Neander’s hymns were written in Düsseldorf, where, new evidence suggests, Neander caused a lot of problems with the Reformed Church. When Neander began working at the Latin School, which was run by the church, he got on amicably with the minister and elders. He accepted invitations to preach and visit the sick but soon tried to introduce new practices without permission, such as private prayer meetings. As the relationship between Neander and the Church began to crumble, Neander did even more to provoke the elders, for instance, refusing to attend Holy Communion because he did not want to sit in the same building as the “unconverted”. The final straw came when Neander made changes to the timetable and buildings at the school. Neander was subsequently suspended. All Neander’s hymns were written in German, however, those that have been translated into English include All my hope on God is founded and Praise to the Lord, the Almighty, the King of Creation. The latter, known as Lobe den Herren in German, was a favourite of King Frederick William III of Prussia, who first heard it in 1800. The composer, Johann Sebastian Bach, based his Chorale cantata, Praise the Lord, the mighty King of honour, on Neander’s words. The hymn paraphrases Psalm 103 (a.k.a Bless the Lord, O my soul) and Psalm 150 (Praise ye the Lord). There are at least ten English translations of Praise to the Lord, the Almighty, the King of Creation, but our modern version is based on the translation by Catherine Winkworth in 1863. Catherine Winkworth was born on 13th September 1827 in Holborn, London, to Henry Winkworth, a silk merchant. At the age of two, Winkworth moved with her family to Manchester where her father had a silk mill. Winkworth’s education was overseen by the Unitarian minister Reverend William Gaskell and a religious philosopher, Doctor James Martineau. The Winkworth family later moved to Bristol where she got a position as the secretary of the Clifton Association for Higher Education for Women. Winkworth was a feminist and is remembered at Clifton High School for Girls where a school house is named after her. Catherine Winkworth spent a year in Dresden where she developed a fascination of German hymnody. In 1854, she published the book Lyra Germanica, which consisted of a collection of German hymns that she had translated, including one by Joachim Neander. Unfortunately, Winkworth’s career as a translator was cut short when she died suddenly from heart disease whilst in Switzerland. She is commemorated on the liturgical calendar of the Episcopal Church with a feast day on 7th August, the same day as the hymn writer and priest John Mason Neale. Araminta “Minty” Harriet Tubman was born into slavery in Maryland but later escaped and became one of the main leaders of the “Underground Railroad” which led hundreds of slaves to freedom. It is not certain when Harriet and her eight siblings were born but it is estimated to be between 1815 and 1825. Plantation owners owned her parents, Harriet “Rit” Green and Ben Ross, and some of their children were sold to other plantations in other states.

Physical violence was a common occurrence for Harriet and her family, particularly in the form of whipping. Harriet carried scars on her back for the rest of her life. On one occasion, when she refused to do something, Harriet’s overseer threw a two-pound weight at her head, knocking her out. This led to seizures, headaches and narcolepsy, which she suffered for the rest of her life. On the other hand, the seizures caused her to fall into intense dream states, which she believed to be religious experiences. Harriet’s father became a free man at the age of 45, however, having nowhere to go, he remained working on the plantation in slave-like conditions. He did not feel he could leave his family, who remained in the possession of the plantation owners. Even when Harriet married John Tubman, a free man, in 1844, she was not released from slavery. In 1849, Harriet made her first trip from South to North following a network known as the Underground Railroad. Following the death of her owner, Harriet decided to escape from slavery and run away to Philadelphia. On 17thSeptember 1849, Harriet and two of her brothers began the long journey but after they learnt that Harriet was being sought in the papers for a reward of $300, the boys had second thoughts and returned home. Harriet’s husband had also refused to go with her and later took on a new wife. Continuing alone, Harriet travelled almost 90 miles to Philadelphia where she finally entered a Free State. “When I found I had crossed that line, I looked at my hands to see if I was the same person. There was such a glory over everything; the sun came like gold through the trees, and over the fields, and I felt like I was in Heaven.” But this was not the end of Harriet’s story. No sooner had she arrived that she returned to the South to help more than 300 people escape from slavery. Between 1850 and 1860, Harriet made 19 trips, the first being to help her niece Kessiah and family escape the harsh conditions. Things became harder when the Fugitive Slave Law came into practice, stating that escaped slaves could be arrested and returned to their owners even if they were living in Free States. Nonetheless, Harriet persevered, rerouting the Underground Railroad to Canada. Harriet had a prophetic vision about the abolitionist John Brown, who she later met in 1858. Although Brown advocated violence, he ultimately wanted the same result as Harriet and they began working together. Unfortunately, Brown was arrested and executed for which Harriet praised him as a martyr. During the Civil War, Harriet entered the Union Army as a cook and nurse, although ended up working as an armed scout and spy. She was the first woman to lead an armed expedition during the war, which resulted in the liberation of over 700 slaves in South Carolina. In 1859, Harriet bought a small piece of land near Auburn, New York from fellow abolitionist Senator William H. Seward. Ten years later, she married Civil War veteran Nelson Davis and in 1874 adopted a baby girl called Gertie. They lived happily in their own home, however, were never financially secure. Friends and supporters endeavoured to raise money for her. One fan, Sarah H. Bradford wrote Harriet’s biography and gave her all the proceeds. In 1903, Harriet opened her land to the African Methodist Episcopal Church and, five years later, opened the Harriet Tubman Home for the Aged. Sadly, Harriet’s health was not good. The physical abuse she received as a slave caused her severe problems, resulting in brain surgery to alleviate some of the pain. She eventually died in 1917 from pneumonia and was buried at Fort Hill Cemetery with military honours. At the end of the 20th century, Harriet Tubman was named one of the most famous civilians in American History and she is soon to be the face on the new $20 bill. Yet, outside of America, Harriet remains unknown, however, last year a film was released titled Harriet, which documents her life as a conductor of the Underground Railroad. A Woman Called Moses from 1978 also documented her career. So, perhaps Harriet Tubman may not remain unknown in Europe for long. I was due to attend Spring Harvest this Easter but, for obvious reasons, it was cancelled. Fortunately, all the talks, services and so forth were uploaded to YouTube, so I did not miss out. During one of the sessions, I learnt about a woman called Henrietta Mears and thought you would like to know a bit about her too.

Henrietta Cornelia Mears was born on 23rd October 1890 in North Dakota, the seventh child of a banker and a Baptist laywoman. When she started Kindergarten, Henrietta protested saying it was “to amuse little children, and I'm amused enough. I want to be educated." Following this, at the age of seven, Henrietta declared she was ready to become a Christian and joined the First Baptist Church of Minneapolis, near where the family had moved in 1893/4. Sadly, Henrietta was a sickly child and by the age of 12 had developed muscular rheumatism. Her condition began to improve, which she believed to be the result of healing prayers, however, her eyesight worsened. She was advised to give up on her education by doctors who believed that if she continued to study, she would be blind by the age of 30. Yet, Henrietta was steadfast in her aim to attend the University of Minnesota and put her foot down, saying, "Then blind I shall be—but I want something in my head to think about." Fortunately, she was still able to see when she graduated in 1913 and began to teach chemistry at the Central High School in Minneapolis. Henrietta continued to attend the First Baptist Church where she was encouraged to turn Sunday Schools into educational opportunities. After working there for ten years, Henrietta took a sabbatical year to think about where to enter Christian work full-time. Whilst there, she visited the First Presbyterian Church Hollywood and met the pastor, Stuart MacLennan, who offered her the position of Director of Christian Education. The new role meant Henrietta had to permanently move to California, where she was put in charge of training Sunday School teachers. She implemented an age-appropriate curriculum that covered everyone from birth to adulthood. She believed Sunday Schools were the best way to teach others about the Bible. Within two years, attendance at the Sunday school had risen from 450 to more than 4200 young people per week. Her training program attracted 6500 people and she delivered many of the lessons herself. Henrietta Mears has been heralded one of the most influential Christian leaders of the 20th century. She founded Gospel Light, a publishing company to print her training materials and set up Forest Home, a Christian conference centre. She also pioneered Gospel Literature International, which inspired the ministries of hundreds of people, including the evangelist Billy Graham (1918-2018). Although Henrietta Mears did not invent the concept of Sunday school, she completely changer its purpose and how it was run. Sunday schools today still follow her guidelines and her book, What the Bible is All About, has sold over 3 million copies. Sadly, we have no children in our church at the moment, but when we do in the future, we can look to Henrietta Mears as a model for our Sunday School. |

©Copyright

We are happy for you to use any material found here, however, please acknowledge the source: www.gantshillurc.co.uk AuthorRev'd Martin Wheadon Archives

June 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed