|

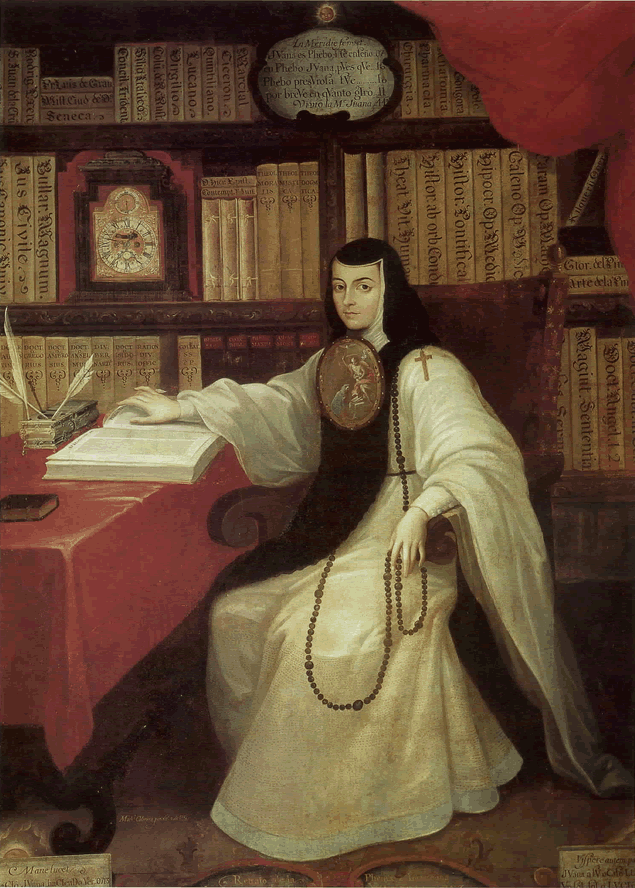

Juana Inés de Asbaje y Ramírez de Santillana was born on 12th November 1648 in the village of San Miguel Nepantla near Mexico City. Although she had older sisters, Juana was an illegitimate child because her parents never married. Her father, a Spanish captain called Pedro Manuel de Asbaje, abandoned the family shortly after Juana’s birth. Her mother was a Criolla woman called Isabel Ramírez. The Corillo people were Latin Americans with Spanish ancestors, which gave them more authority in Colonial Mexico, which belonged to the Spanish Empire. Juana’s father was Spanish, and her maternal grandparents were Spanish, thus making her a Criolla. Despite the lack of care from her biological father, Juana grew up in relative comfort on her maternal grandfather’s Hacienda, the Spanish equivalent of an estate. Her favourite place was the Hacienda chapel, where Juana hid with books stolen from her grandfather’s library. Girls were forbidden to read for leisure, but this did not prevent Juana from learning to read and write. At the age of three, Juana followed her sister to school and quickly learned how to read Latin. Allegedly, by the age of 5, Juana understood enough mathematics to write accounts, and at 8, wrote her first poem. By her teens, Juana knew enough to teach other children Latin and could also understand Nahuatl, an Aztec language spoken in central Mexico since the seventh century. It was unusual for those of Spanish descent to speak the native languages. The Spanish aimed to replace the Mexicano tongue with their Latin alphabet, so it was almost with defiance that Juana went out of her way to not only learn Nahuatl but compose poems in the language too. Juana finished school at 16 but wished to continue her studies at university. Unfortunately, only men could receive higher education. Juana spoke to her mother about her aspirations, suggesting she could disguise herself as a man to attend the university in Mexico City. Despite her pleading, Juana’s mother refused to allow her daughter to attempt such a risky plan. Instead, Isabel sent Juana to the colonial viceroy’s court to work as a lady-in-waiting. Under the guardianship of the viceroy’s wife, Leonor de Carreto (1616-73), Juana continued her studies in private. Yet, she could not keep her ambitions secret from her mistress, who informed the viceroy of Juana’s intelligence. Rather than reprimanding her, the viceroy Antonio Sebastián Álvarez de Toledo (1622-1715) took interest in Juana’s education. Wishing to test Juana’s intellect, the viceroy arranged a meeting of several theologians, philosophers, and poets and invited them to question the young girl. The men quizzed Juana on many topics, including science and literature, and she managed to impress them with her answers. They also admired how Juana conducted herself, and she remained unphased by the difficult questions they threw at her. News of the meeting spread throughout the viceregal court. No longer needing to hide her writing skills, Juana produced many poems and other writings that impressed all those who read them. Her literary accomplishments spread across the Kingdom of New Spain, which covered much of North America, northern parts of South America and several islands in the Pacific Ocean. Yet, female scholars and writers were an anomaly at the time, and rather than attract praise, Juana drew the attention of many suitors. After refusing many proposals of marriage, Juana felt desperate to escape from the domineering men. She wanted “to have no fixed occupation which might curtail [her] freedom to study.” The only safe place she could find where she could continue her work was the Monastery of St. Joseph, so she became a nun. Juana spent over a year with the Discalced Carmelite nuns as a postulant, then moved to the monastery of the Hieronymite nuns in 1669, preferring their more relaxed rules. The San Jerónimo Convent, which became Juana’s home for the rest of her life, was established in 1585 by Isabel de Barrios. Only four nuns lived in the building at first, but they soon grew in number, becoming one of the first convents of nuns of the Saint Jerome order. They based their role in life on the biblical scholar Saint Jerome (342-420), who translated most of the Bible into Latin. Known for his religious teachings, Jerome favoured women and identified how a woman devoted to Jesus should live her life. During his lifetime, Jerome knew many women who had taken a vow of virginity. He advised them on the clothing they should wear, how to conduct themselves in public, and what and how they should eat and drink. Despite taking on the title “Sor”, the Spanish equivalent of sister, Sor Juana’s main aim was to focus on her literary pursuits. Whilst she followed the ways of the Hieronymite nuns, she spent all her spare time writing. Juana’s previous employers, the Viceroy and Vicereine of New Spain became her patrons, helping her publish her work in colonial Mexico and Spain. Sor Juana also received support from the intellectual Don Carlos de Sigüenza y Góngora (1645-1700), who shared her religious beliefs as well as her passion for literature. Sigüenza, who claimed, “There is no pen that can rise to the eminence … of Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz,” also encouraged Juana to explore scientific topics. Sor Juana dedicated some of her works, particularly her poems, to her patrons. Those written for Vicereine Leonor de Carreto often featured the name Laura, a codename assigned by Juana. Another patron, Marchioness Maria Luisa Manrique de Lara y Gonzaga (1649-1721) was “Lysi”. Juana also wrote a comic play called Los empeños de una casa (House of Desires) for Doña Maria Luisa and her husband in celebration of the birthday of their first child, José. The first performance of Los empeños de una casa took place on 4th October 1683 and contains three songs in praise of Doña María Luisa Manrique: “Divine Lysi, Let Pass“, “Beautiful María” and “Tender Beautiful Flower Bud”. The protagonist, Doña Ana of Arellano, resembles the marchioness, who Sor Juana held in high regard. The play features two couples who are in love but cannot be together. Mistaken identities cause the characters much distress and the audience much hilarity. By the end of the final scene, everyone pairs up with the right partner, except one man who remains single as a punishment for causing the initial deception. In terms of theme and drama, Los empeños de una casa is a prime example of Mexican baroque theatre. Another play by Sor Juana premiered on 11th February 1689 to mark the inauguration of the viceroyalty Gaspar de la Cerda y Mendoza (1653-97). Sor Juana based Love is but a Labyrinth on the Greek mythological story of Theseus and the Minotaur. Theseus, the king and founder of Athens, fights against the half-bull, half-human Minotaur to save the Cretan princess Ariadne. Although Theseus resembled the archetypal baroque hero, Sor Juana portrayed him as a humble man rather than proud. Not all of Sor Juana’s writings were intended for public consumption. In 1690, Manuel Fernández de Santa Cruz (1637-99), the Bishop of Puebla, published Sor Juana’s critique of a sermon by the Jesuit priest Father António Vieira (1608-97). Titled Carta Atenagórica (Athenagorical Letter or a letter “worthy of Athena’s wisdom”), Juana expressed her dislike of the colonial system and her belief that religious doctrines are the product of human interpretation. She criticised Father António Vieira for his dramatic and philosophical representation of theological topics. Most importantly, Juana called the priest out for his anti-feminist attitude. Alongside Sor Juana’s critique, the Bishop of Puebla published a letter under the pseudonym Sor Filotea de la Cruz, in which he admonished the nun for her opinions. Ironically, the bishop agreed with many of Sor Juana’s thoughts, but he ended the letter by saying Sor Juana should concentrate on religious rather than secular studies. Whilst the critique focused on a religious sermon, Sor Juana included colonialism and politics in her argument, which the bishop felt were inappropriate topics for a woman, let alone a nun. Sor Juana responded to Sor Filotea, the Bishop of Puebla, in which she defended women’s rights to education and further study. Whilst she agreed that women should not neglect their duties, in her case her obedience to the Church and God, Juana pointed out that “One can perfectly well philosophise while cooking supper.” By this, she meant women could balance their education and everyday tasks. She jokingly followed this with the quip, “If Aristotle had cooked, much more would have been written.” In her response, Sor Juana quoted the Spanish nun St Teresa of Ávila (1515-82) as well as St Jerome and St Paul to back up her argument that “human arts and sciences” are necessary to understand sacred theology. She suggested if women were elected to positions of authority, they could educate other women, thus alleviating a male tutor’s fears of being in intimate settings with female students. The nun’s controversial response caused a lot of concern amongst high-ranking (male) officials who criticised her “waywardness”. They were angry with Sor Juana for challenging the patriarchal structure of the Catholic Church, and for claiming her writing was as good as historical and biblical texts. As a result, the San Jerónimo Convent forbid Juana from reading and sold her collection of over 4,000 books and scientific instruments for charity. With no one on her side, Sor Juana relented and agreed to renew her vows. The convent also required Juana to undergo penance, but rather than signing the penitential documents with her name, she wrote: “Yo, la Peor de Todas” (I, the worst of all women). From 1693 onwards, Sor Juana focused solely on her religious orders. Never again did she pick up a pen to write or a book to read. Instead, Juana spent her time either in prayer or tending the sick, which led to fatal consequences. After nursing other nuns stricken during a plague, Sor Juana fell ill and passed away on 17th April 1695. To read the full article, click here This blog post was published with the permission of the author, Hazel Stainer. www.hazelstainer.wordpress.com

0 Comments

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

©Copyright

We are happy for you to use any material found here, however, please acknowledge the source: www.gantshillurc.co.uk AuthorRev'd Martin Wheadon Archives

June 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed