|

This article was originally posted on www.hazelstainer.wordpress.com on 18/12/20. Hazel has kindly allowed us to repost her work to coincide with our blogs about Black Lives Matter. In the National Gallery, is a painting called The Sharp Family by Johann Zoffany (1733-1810), a German neoclassical painter. Zoffany, who spent his early years in England under the patronage of George III (1738-1820) and Queen Charlotte (1744-1818), captured the Sharp Family making music aboard their pleasure boat, Apollo, with All Saints Church, Fulham in the background. The Sharp siblings regularly appeared on the River Thames with their instruments to entertain the public on the banks. Produced between 1779-1781, Zoffany’s painting indicates the wealth of the family through the portrayal of the upper-class fashions of the 18th century. Their musical boating parties attracted many people, evidencing their popularity, particularly among local dignitaries and even royalty. Yet, the family came from a more humble background. The siblings grew up in Durham with their parents, Thomas Sharp (1693–1759), Archdeacon of Northumberland, and Grace Higgons, the daughter of English clergyman and travel writer George Wheler (1651-1724). Although they had an honourable upbringing, they did not have the financial advantages of the upper classes. Through sheer determination, love of music and fondness for each other, the Sharps worked their way up the ranks, first giving recitals at one of the brother’s home, before performing fortnightly water-borne concerts on their large barge between 1775-1783. Seated in the centre of the painting is the most well-known of the Sharp siblings. Granville Sharp, born in Durham in 1735, played a variety of instruments, including the clarinet, oboe, flageolet, kettle drums, harp and a double-flute. He also sang with an impressive bass voice, which George III described as “the best in Britain”. Respected for his musical skills, Granville often signed his name G#, but it was not only in music that he made his name. At the time of Granville’s birth, he had eight older brothers, although only five survived infancy. Five sisters soon followed, bringing the total number of children to 14. Their parents put away money for the children’s education, but by the time Granville reached his teens, the money was exhausted. Although he began his schooling at the all-boys school in Durham, Granville and his siblings received most of their tuition at home. At the age of 15, Granville travelled to London to work as an apprentice for a linen draper. He found the work tiresome and longed for opportunities to hold discussions, arguments and debates. To fuel his passion, Granville took an interest in his fellow apprentices, learning Greek in order to debate the orthodox Bible with a Socinian colleague (someone who believes in God and Christian ideals but not the divinity of Jesus). He also learnt Hebrew so as to have theological discussions with a Jewish friend. Not all of the Sharp brothers entered apprenticeships. The eldest, John, followed his father’s footsteps and was ordained into the Church. Whilst their father had not found wealth in that position, John worked hard to establish a miniature welfare state in his home in Bamburgh Castle, Northumberland where he was the perpetual curate. During his career, John oversaw the establishment of a school, a library, a hospital, and the first lifeboat service. At the age of 14, William Sharp (1729-1810) moved to London to study surgery. His exceptional skill and demeanour attracted the patronage of George III, who hired William as his private surgeon. After attending to Princess Amelia (1783-1810), who was often in poor health, the king offered William a baronetcy, which he turned down. Although William was well-off, he never forgot his past and paid attention to the needs of the poor. He considered his high position in society to be a stroke of luck, so established a free surgery for those denied such good fortune. Like Granville, his brother James came to London as an apprentice. After completing his apprenticeship in ironmongery, James rose through the ranks to become a pioneer of the industrial revolution. James enjoyed making music in his spare time, often meeting with Granville and William, as well as his sisters Elizabeth and Judith who had also moved to London. The siblings usually met at William’s house in Mincing Lane, where they also gave concerts. Unfortunately, James passed away before the family began performing on the Thames. Granville’s apprenticeship came to an end in 1757, the same year both his parents passed away. He quickly secured himself the position of Clerk in the Ordnance Office at the Tower of London, a civil service position, that also provided enough free time to pursue his musical talents and intellectual hobbies. Being so close to his siblings, both familially and geographically, allowed his passion for music to flourish. He also discussed his work with his brothers, who informed him of the goings-on in their careers. On a visit to William’s surgery in 1765, Granville met a young black slave with severe wounds to his head. The slave, Jonathan Strong, originally from Barbados, received the injuries from his master David Lisle, who bashed the young lad repeatedly over the head with a pistol. After almost blinding him, Lisle discarded Strong on the streets where he was discovered and taken to William’s free surgery. Granville assisted William to treat Strong, but his condition was so severe, they needed to transfer him to St Bartholomew’s Hospital. Out of the kindness of their hearts, Granville and William paid for Strong’s four-month stay. After Strong left hospital, the Sharp brothers continued to look after him. When he was strong enough, they found him employment with a Quaker apothecary, where he worked for a year and a half before being discovered by his previous master. David Lisle, a lawyer, believed he still owned Strong, despite discarding him in the street two years previously. Lisle wished to sell Strong to his friend James Kerr of Harley Street for £30. Kerr owned a plantation in Jamaica and wanted to ship Strong to the Caribbean to work there. Lisle and Kerr employed two men to kidnap Strong but did not anticipate the slave’s new contacts. Following his capture, Strong managed to get word to Granville, who immediately went to the Lord Mayor of London to plead his case. The Lord Mayor, possibly Sir Thomas Davies, in turn, spoke to Lisle and Kerr about their claim on the slave. Kerr produced the bill of sale to prove he had purchased Strong from Lisle, but without more evidence, the Lord Mayor ordered Strong’s release from his imprisonment. The case, however, was far from over. Almost immediately after his release, a second kidnap attempt took place, this time by West India Captain David Laird, who threatened to take Strong straight to James Kerr. Fortunately, Granville witnessed the attack and claimed he would charge Laird with assault if he did not let the young man go. Meanwhile, Lisle tried to sue Granville £200 for taking his property. When Granville approached his lawyers on the subject, they told him Lisle had every right to claim Strong as his possession. Unable to “believe the law of England was really so injurious to natural rights,” Granville spent the following two years studying English laws. Lisle soon gave up the fight, but Kerr remained determined to win his case. After two years of persisting, the court dismissed the case and fined Kerr for time-wasting. For the first time in his life, twenty-year-old Jonathan Strong was a free man. Sadly, his freedom did not last long, and he passed away five years later. Granville’s association with Jonathan Strong earned him the moniker “protector of the Negro”. A couple of slaves approached Granville for support, hoping for similar results, but the courts were reluctant to be involved in human possession disputes. At this time, British organisations were the largest slave traders in the world. Slave labour was vital for the British economy, therefore, owners were reluctant to free their slaves. Determined to put an end to slavery, Granville published A Representation of the Injustice and Dangerous Tendency of Tolerating Slavery: Or Admitting the Least Claim of Private Property in the Persons of Men in England in 1769. He expressed the view that “the laws of nature” make everyone equal and it is only laws imposed by society that state otherwise. He demonstrated that slavery was illegal because the freedom of a man was priceless. Granville received support from James Oglethorpe (1696-1785) of Cranham Hall, the founder of the American state of Georgia. Together, they unsuccessfully attempted to convince British leadership to give slaves the same rights as Englishmen. Slavery had never been authorised by law in England and Wales. Granville used this to his advantage when learning of the plight of another black slave in 1772. James Somerset, an enslaved African, travelled to England with his American owner Charles Stewart in 1769 but managed to escape a couple of years later. Unfortunately, slave hunters found Somerset and locked him in a ship bound for Jamaica. Before Somerset attempted to flee, Charles Stewart had him baptised as a Christian. On learning of his capture, three of Somerset’s Godparents complained to the courts. When Granville heard of the case, he supplied the lawyers supporting Somerset with his formidable knowledge of English laws. Granville proved that slavery was illegal under English law, so Somerset became a free man the moment he stepped on English soil. Although the court case lasted five months, the Chief Justice of the King’s Bench, William Murray, Lord Mansfield (1705-93), announced James Somerset’s freedom and ended the proceedings. Somerset and his supporters celebrated the result, but this was not the end of slavery. Whilst it was illegal to own a slave in England, the law condoned using slaves in overseas territories. Plantation owners in the Americas continued to exploit slaves, abducting them from their homes in Africa and forcing them to work in harsh conditions in a foreign land. In 1781, 60 slaves died from neglect and over-crowding aboard the British slave ship Zong, causing the crew to take drastic action, massacring over 130 slaves by throwing them overboard. To add to the morally corrupt event, the shipowner tried to claim compensation for the loss of his property at sea. Granville learnt of the massacre in 1783 from Olaudah Equiano (1745-97), a freed slave from the Kingdom of Benin. Horrified by the events aboard the Zong, Granville immediately involved himself with the court case against the Liverpool merchant claiming insurance. The merchant’s lawyer John Lee (1733-93) claimed: “the case was the same as if assets had been thrown overboard.” Granville argued that jettisoning slaves was murder and should be punished accordingly. Unfortunately, the judge dismissed Granville’s accusation but ruled the slave owner could not file for insurance due to lack of evidence. The more Granville learnt about the lives of slaves, the greater his wish to abolish slavery entirely. He was not alone with this wish, but the largest groups of anti-slavery protesters were Quakers, a domination forbidden from participating in Parliament. In 1787, nine Quakers and three Anglicans established the Society for Effecting the Abolition of the Slave Trade, but to make an impact, they needed someone with parliamentary connections. A vote unanimously elected Granville, one of the Anglican founders of the society, to present their petitions. Due to modesty, Granville refused to chair the meetings for the society but regularly attended for the following twenty years. Parliament rejected many of their petitions, but they continued to work tirelessly nonetheless. The society received support from other anti-slavery campaigners, including the founder of the Wedgwood company Josiah Wedgwood (1730-95), who arranged the production of anti-slavery medallions, and the politician William Wilberforce (1759-1883), who presented the first Bill to abolish the slave trade in 1791, albeit unsuccessful. Through Granville’s connections, the society also received support from abolitionists in America. Granville made attempts to return freed-slaves in Britain to their native countries. Many worried they would return to slavery, so Granville drew up plans for a new Christian society called “The Province of Freedom”. The first attempt struggled from the start, with fires on ships and many Africans returning home before the plans were fully operational. The first settlement, named Granville Town, lasted a few months before local tribes burnt it down. A second attempt to create “The Province of Freedom” proved more successful. With the help of a former American slave, Thomas Peters (1738-92) and British brothers, Thomas Clarkson (1760-1846) and John Clarkson (1764-1828), Granville helped to found the port city Freetown in Sierra Leone. In 1807, the society’s hard work paid off when the Houses of Parliament passed the Slave Trade Act/Act of Abolition. When Granville, now 71 years old, heard the news, he fell to his knees in prayer. Many of the original abolitionists did not live to see the result and Granville received the affectionate accolade of the “grand old man of the abolition struggle”. As well as anti-slavery campaigns, Granville supported American colonists, which meant resigning from his job due to its support for the British forces fighting in America. Away from politics, Granville enjoyed his music but also established the British and Foreign Bible Society (now known as the Bible Society) with Wilberforce and Methodist preacher Thomas Charles (1755-1814) to spread the use of the scriptures throughout the world. Initially, the society focused on printing bibles in Welsh but soon produced bibles in Scots Gaelic and Manx Gaelic. They sent Gospels abroad in the languages of the Iroquois and Romani people in Canada and America to make the Bible accessible for more people. By 1824, the British and Foreign Bible Society had “distributed 1,723,251 Bibles, and 2,529,114 Testaments—making a total of 4,252,365.” Today the society is global with 150 Bible Societies around the world. Granville Sharp passed away on 6th July 1813 before he had the chance to see the full effects of the Slave Trade Act. His tomb lies beside the graves of his siblings William and Elizabeth in All Saints Church, Fulham, which is visible in the background of the painting of the Sharp family. “Here by the Remains of the Brother and Sister whom he tenderly loved lie those of GRANVILLE SHARP Esqr. at the age of 79 this venerable Philanthropist terminated his Career of almost unparalleled activity and usefulness July 6th 1813 Leaving behind him a name That will be Cherished with Affection and Gratitude as long as any homage shall be paid to those principles of JUSTICE HUMANITY and RELIGION which for nearly half a Century He promoted by his Exertions and adorned by his Example“ INSCRIPTION ON GRANVILLE SHARP’S TOMB A memorial in Westminster Abbey remembers the life of Granville Sharp and, in 2007, he featured on the 50p Royal Mail stamp issued to commemorate the 200th anniversary of the abolition of slavery in the United Kingdom. His is also memorialised in Granville Town in Sierra Leone and Granville in Jamaica, both named in his honour. The Sharp Family by Johann Zoffany intrigues viewers, who wonder about the identity of the musical family and the reason behind their public concerts. At a glance, it is impossible to tell that one family member made such an impact in the 18th century, helping to bring about changes that continue to shape our societies today. Granville’s legacy suggests that not everyone has forgotten him, but the majority of people have not heard his name. It goes to show how quickly good deeds of others are overshadowed by new events, which in turn get buried beneath the ever-growing pile of history. In an attempt to discover the Sharp Family in Zoffany’s painting, a lesser-known period of Georgian Britain has emerged. Next time you view a portrait of someone you have not heard of, “google” them. You may be surprised by what you learn.

2 Comments

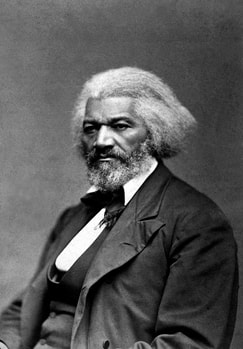

"I would unite with anybody to do right and with nobody to do wrong.” These are the words of American social reformer, writer, and statesman Frederick Douglass who escaped slavery in Maryland to become a national leader of the abolitionist movement. Many found it astonishing that such a successful orator was once a slave, proving false the misconception that slaves lacked the intelligence of independent Americans. Douglass believed everyone was equal regardless of their skin tone and heritage. He was also an active supporter of women’s suffrage.

Frederick Augustus Washington Bailey was born on a plantation in Maryland to Harriet Bailey, a woman of African and Native American ancestry. His father was white, possibly European, but Frederick never knew him, nor did he know on which day or in which year he was born. Historians estimate his year of birth as 1818 and Frederick chose 14th February as the day to celebrate his birth. Separated from his mother at a young age, the infant Frederick lived with his grandparents, Betsy, a slave, and Isaac, a free man. At the age of six, Frederick’s master transferred him to another plantation, but two years later he moved again to a household in Baltimore. Despite being the property of Hugh Auld, his master’s wife Sophia ensured Frederick was well fed and clothed. When he was about 12 years old, Sophia taught him to read and write until her husband put an end to their lessons. Yet, Frederick continued to teach himself in secret, often observing the white children in the city. He believed "knowledge is the pathway from slavery to freedom.” In 1833, Frederick went to work for Edward Covey, a farmer who repeatedly whipped him. Frederick attempted to run away, but his master caught him in the act. In 1837, he met and fell in love with Anna Murray (1813-88), a free black woman, who encouraged him to have another attempt at escaping. On 3rd September 1838, Frederick succeeded by sneaking onto a train to Harve de Grace dressed as a sailor. He then made his way to New York to meet up with Anna. Frederick and Anna married on 15th September 1838, initially adopting the surname Johnson. Inspired by the poem The Lady of the Lake by Walter Scott (1771-1832), Frederick changed their surname to Douglass after the names of the principal characters. They joined the independent African Methodist Episcopal Zion Church, and Frederick became a preacher in 1839. Soon after, at the approximate age of 23, Frederick Douglass gave his first speech about his experiences as a slave at the Massachusetts Anti-Slavery Society's annual convention. From then on, Douglass involved himself with many anti-slavery protests and conventions, resulting in physical attacks from slavery supporters. One occasion caused irreparable damage to Douglass’s hand. He exclaimed, "I have no love for America, as such; I have no patriotism. I have no country. What country have I? The Institutions of this Country do not know me—do not recognize me as a man.” Yet, he continued to fight to put an end to slavery. As well as oration, Douglass published many works, including his first autobiography, Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, an American Slave in 1845, My Bondage and My Freedom in 1855, and Life and Times of Frederick Douglass in 1881. In 1845, Douglass travelled to Ireland and England where he was amazed at the different treatment he received, not "as a color, but as a man.” Focusing on the abolition of slavery, Douglass gave many speeches in churches and chapels, drawing large crowds. He met with Thomas Clarkson (1760-1846) who had campaigned for the Slave Trade Act of 1807. Most importantly, while he was in Britain, Douglass legally became a free man. With £500 from English supporters, Douglass returned to the USA in 1847 and established his first abolitionist newspaper, the North Star. The paper adopted the motto "Right is of no Sex – Truth is of no Color – God is the Father of us all, and we are all brethren” to attract a diverse readership. Meanwhile, Douglass and his wife helped over four hundred slaves escape on the Underground Railroad network managed by Harriet Tubman. Douglass was the only African American to attend the first women’s rights meeting in New York. Douglass said he could not accept the right to vote as a black man until women also had the opportunity. "Discussion of the rights of animals would be regarded with far more complacency...than would be a discussion of the rights of women." Unfortunately, Douglass received criticism when he paid more attention to the campaign to allow black men the right to vote, but he maintained he was never against women’s rights. He feared linking black men’s suffrage with women’s suffrage would result in a failure for both; it was better to focus on one at a time. During the Civil War, Douglass met with President Abraham Lincoln (1809-65) to discuss the treatment of black soldiers. This meeting led to the declaration of the 13th amendment, outlawing slavery. After the assassination of Lincoln, Douglass met with President Andrew Johnson (1808-75) on the subject of black suffrage. In 1868, the 14th amendment gave blacks equal protection under the law, and in 1870 they finally won the right to vote. Due to his achievements, Douglass received several political appointments, including president of the Freedman’s Savings Bank and chargé d'affaires for the Dominican Republic. In 1872, Douglass became the first African American nominated for Vice President of the United States, although he was nominated without his knowledge. The same year, he was the presidential elector at large for New York. Douglass and Anna had five children during their marriage of 44 years. Their eldest, Rosetta Douglass (1839-1906) was a founding member of the National Association for Colored Women and also helped with her father’s newspaper business, as did Lewis Henry Douglass (1840-1908) and Frederick Douglass Jr. (1842-92). Their youngest son, Charles Remond Douglass (1844-1920) also helped with the papers and was the first African-American man to enlist in the military in New York during the Civil War. Annie Douglass, their youngest child, passed away at the age of ten. Anna passed away in 1882, and two years later Douglass remarried to suffragist Helen Pitts (1838-1913). This caused controversy and upset Douglass’ children because Helen was twenty years younger than their father. She was also white. Douglass responded to criticism by saying his first marriage was to a woman of his mother’s colour, and his second to someone of his father’s colour. Douglass continued to speak at meetings across the USA and further abroad. In 1888, he became the first African American to receive a vote for President of the United States. President Benjamin Harrison (1833-1901) won the election and made Douglass the consul-general to the Republic of Haiti. On 20th February 1895, Douglass attended a meeting with the National Council of Women in Washington, D.C where he received a standing ovation. That evening after returning home, he suffered a fatal heart attack. Thousands of supporters attended his funeral, and four years later they erected a statue in his memory. He was the first African American to be memorialised in this way. Frederick Douglass continues to receive such honours today. Statues of Douglass stand in the United States Capitol Visitor Centre, Central Park, and the University of Maryland.

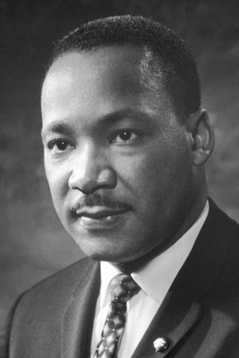

Martin Luther King Junior was an American minister who became the spokesperson and leader of the Civil Rights Movement in 1955 until his assassination in 1968. He is a hero and inspiration for the recent Black Lives Matter campaign and was instrumental in combating racial inequality in the United States.

Born in Atlanta, Georgia, on 15th January 1929, he was originally named Michael, although his father, Reverend Michael King Snr, claimed this to be a mistake. Apparently, his mother, Alberta, gave him the name Michael, which a physician entered onto the birth certificate without consulting the father. Nonetheless, after a trip to Germany in 1934 where he learnt about the German professor Martin Luther, Michael King Snr began referring to himself as Martin Luther King and his son as Martin Luther King Jr. On 23rd July 1957, Junior’s name was officially changed on his birth certificate. King and his two younger siblings, who grew up listening to bible stories, lived in harmony with black and white children until they began school. It was then that King noticed the difference in treatment between black and white. King had no choice but to attend Younge Street Elementary School for black children and was told he was no longer allowed to play with his white friends. His father refused to accept segregation laws and led protests and marches in Atlanta. King Jr began to resent racial humiliation during his teenage years. He also began to question Christian claims. He had grown up memorising bible passages and hymns but his experiences as a black boy made him question the authenticity of Christian beliefs. Fortunately, his mentor at college, a Baptist minister, who also became his spiritual mentor, encouraged King to follow in his father’s footsteps. After graduating from college, King enrolled at Crozer Theological Seminary in Upland, Pennsylvania. In 1951, King began his doctoral studies in systematic theology at Boston University and the following year he was called as pastor of the Dexter Avenue Baptist Church in Montgomery, Alabama. Whilst studying in Boston, King met Coretta Scott, who he later married on 18th June 1953. Over the next decade, the Kings became the parents of four children: Yolanda King (1955–2007), Martin Luther King III (b. 1957), Dexter Scott King (b. 1961), and Bernice King (b. 1963). In 1955, a schoolgirl, Claudette Colvin, refused to give up her seat for a white man in protest of the enforced racial segregation laws. King, who was on the Birmingham African-American community, looked into the case, but it was eventually dismissed on account of Colvin being a minor. Later that year, a similar incident occurred when Rosa Parks was arrested for refusing to give up her seat. As a result, King led a boycott of the buses in Montgomery, which lasted 385 days until King’s house was bombed. Although King was arrested during the campaign, it resulted in the end of racial segregation on all Montgomery public buses. In 1957, King and some other black ministers founded the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC), which aimed to encourage black churches to conduct nonviolent protests in the name of civil rights. The conference was inspired by Reverend Billy Graham who, despite being white, had befriended King and shared his sentiments. During the SCLC’s 1957 Prayer Pilgrimage for Freedom demonstration in Washington, King made his first public speech to the nation. The following year, King published his book Stride Toward Freedom, however, during a book signing in Harlem, he was stabbed in the chest with a letter opener. He narrowly escaped death with the help of surgeons and was hospitalised for three weeks. The attack, however, was deemed not to be a racial offence as the perpetrator was a mentally ill black woman called Izola Curry who believe King was conspiring against her with a group of Communists. After recovering from his near-death experience, King returned to the fore of the Civil Rights movement and led several non-violent protests and marches. These aimed to provide black citizens with the right to vote as well as provide labour and civil rights, most of which were granted in the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the 1965 Voting Rights Act. King, along with the SCLC, involved themselves with uprisings around the country. In Albany, Georgia, King was arrested at a peaceful demonstration in 1961 and again in 1962. The following year in Birmingham, Alabama, King was arrested once again for campaigning against racial segregation and economic injustice. This was his 13th arrest and, by the end of his life, he had been arrested 29 times. Nonetheless, he remained undeterred and joined or organised protests in New York and Florida in 1964. Martin Luther King Jr’s most famous “I have a dream” speech took place during the March on Washington in 1963. The march made demands for the removal of racial segregation in schools, a law to prevent racial discrimination at work, a minimum wage for black workers and protection from police brutality, amongst other things. King’s speech has since been listed as one of the finest speeches in the history of America. “I have a dream that one day, down in Alabama, with its vicious racists, with its governor having his lips dripping with the words of interposition and nullification; one day right there in Alabama, little black boys and black girls will be able to join hands with little white boys and white girls as sisters and brothers.” King continued to organise marches, speeches and protests and, in 1967, involved the SCLC with the protests against the war in Vietnam. Not only was King concerned about black rights, but he also spoke strongly against the USA’s involvement in the war in general. Following this, in 1968, King organised the “Poor People’s Campaign” to address the issues of economic justice across America. By then, some circumstances had improved for black people and King was emphasising that black and white were equal and everyone deserved the same rights. On 29th March 1968, Martin Luther King Jr went to Memphis, Tennessee, to support the strike of black sanitary public works employees, where he delivered his "I've Been to the Mountaintop" speech. “I just want to do God's will. And He's allowed me to go up to the mountain. And I've looked over. And I've seen the promised land. I may not get there with you. But I want you to know tonight, that we, as a people, will get to the promised land. So I'm happy, tonight. I'm not worried about anything. I'm not fearing any man. Mine eyes have seen the glory of the coming of the Lord.” The following evening, whilst standing on the balcony at the Lorraine Motel where he was staying, Martin Luther King Jr was fatally shot in the face by James Earl Ray. Despite being rushed to hospital, King passed away an hour later. His death resulted in mass riots in cities across America until, on 7th April, President Lyndon B. Johnson declared a national day of mourning for the Civil Rights leader. Just days after his death, the Civil Rights Act of 1968 was passed prohibiting discrimination in housing and housing-related transactions on the basis of race, religion, or national origin. Despite dying at the age of 39, Martin Luther King Jr’s actions and legacy changed the lives of black people forever. The struggle was by no means over, however, black and white were beginning to live in harmony. His dream that his “four little children will one day live in a nation where they will not be judged by the colour of their skin but by the content of their character,” was finally coming true. Charles Spurgeon was a 19th-century preacher known as the “Prince of Preachers” among many denominations. Spurgeon was mostly involved with the Reformed Baptist tradition, also known as Particular Baptist, and spent a great deal of time opposing the increasingly liberal and pragmatic theological trends in the churches of the day. Many books containing his sermons have been published and read by many generations and Spurgeon continues to inspire people today.

Charles Haddon Spurgeon was born to John and Eliza Spurgeon in Kelvedon near Braintree, Essex on 19th June 1834, although his family relocated to Colchester before his first birthday. Although the Spurgeon family considered themselves Congregationalists, it was not until Charles was 15 that he opened his heart to God. This came about when he was forced to shelter from a snowstorm in a Primitive Methodist chapel. It is said that while he was waiting out the storm, Spurgeon came across the verse Isaiah 45:22 and was immediately converted. "Look unto me, and be ye saved, all the ends of the earth, for I am God, and there is none else." In May 1850, Spurgeon was baptised in the River Lark at Isleham, Cambridgeshire. The same year, he moved to Cambridge to become a Sunday School teacher. That winter, at 16 years old, he preached his first sermon, and thus began his preaching career. His style and insight into the Bible were said to be far above average, not just for his age but in comparison to preachers in general. In 1851, he was made the pastor of a small baptist church in Waterbeach, Cambridgeshire and published his first book, which focused on the Gospels, in 1853. Aged 19, Spurgeon was called to become the pastor of New Park Street Chapel, Southwark, London, which had the largest Baptist congregation at the time. Here, his preaching ability became famous and his sermons were so popular that the "New Park Street Pulpit" began to publish one every week, selling them for a penny each. Later, books were published under the same title as the weekly publication, featuring five volumes of Spurgeon’s sermons. It is estimated over 3,600 of his sermons were printed during his lifetime. Naturally, with greatness came criticism from those who thought Spurgeon’s sermons were too straightforward. Nonetheless, they appealed to the congregation, which had grown to a size of 10,000 by Spurgeon’s 22nd birthday. Unable to fit everyone into the building, the church moved to Exeter Hall on the strand, then the Surrey Music Hall in Newington in order to accommodate everyone. The year 1856 began positively with Spurgeon’s marriage to Susannah Thompson, however, it ended in tragedy. During one of Spurgeon’s sermons at the Surrey Music Hall, someone in the crowd shouted “Fire!”, which spread mass panic and hysteria. Thousands of people immediately ran for the exit, pushing those in their way and crushing anyone who had fallen. Several died as a result and Spurgeon was mentally affected by the scene for the rest of his life. He admitted to sudden, unexplainable tears, which today doctors may identify as a symptom of depression or PTSD. Nonetheless, Spurgeon persevered with his preaching and the following year became the father of twin boys: Charles and Thomas. The same year he founded a pastors’ college, which was renamed Spurgeon’s College in 1923, and, in October, preached to his largest congregation yet. The service took place at The Crystal Palace and welcomed an estimated 23,654 people. Spurgeon’s church could not remain at the Surrey Music Hall forever, so on 18th March 1861, it moved to the purpose-built Metropolitan Tabernacle in Elephant and Castle. The Independent Baptist Church still worships there today. Spurgeon preached there several times a week for the remaining 31 years of his life. The reason it was possible to publish so many, if not all, of Spurgeon’s sermons, was because he wrote them out before each service. When he reached the pulpit, however, all he had with him were a handful of notecards to prompt him, suggesting he had learnt the sermon off by heart. As well as sermons, Spurgeon wrote a handful of hymns, however, he preferred to use popular songs by other writers, such as Isaac Watts. They were mostly sung a capella due to the lack of an organ in the church. Spurgeon did not limit himself to Baptist congregations and frequently preached to other denominations. Nonetheless, his sermons often argued against some of the methods of preaching used by the Church of England. One argument was that a person did not have to be baptised in order to experience salvation. Not only did this argument go against the Church of England, but it also angered other Baptist churches. As a result, the Metropolitan Tabernacle removed itself from the Baptist Union, becoming an Independent Baptist Church. Through his popularity, Spurgeon made many connections with other preachers and philanthropists. He supported the China Inland Mission founded by his friend, James Hudson Taylor, and was inspired by Christian evangelist George Müller to open an orphanage. The orphanage was closed after the Second World War and became Spurgeon’s Child Care charity, which continues to support vulnerable families, children and young people in the United Kingdom. Spurgeon was vocally against slavery, which lost him a few supporters, particularly those from the United States. “... although I commune at the Lord's table with men of all creeds, yet with a slave-holder, have no fellowship of any sort or kind. Whenever [a slave-holder] has called upon me, I have considered it my duty to express my detestation of his wickedness, and I would as soon think of receiving a murderer into my church . . . as a man stealer.” (Spurgeon, Christian Watchman and Reflector, c.1860) Although Spurgeon had the support of his family, his wife was often too ill to leave home and attend his sermons. Yet, she outlived her husband who suffered from rheumatism, gout and Bright's disease in his later years. Spurgeon began making regular trips to the French Riviera to ease his symptoms, which is where he was when he died on 31st January 1892. Spurgeon was buried in West Norwood Cemetery, one of the “Magnificent Seven” cemeteries in London. His son, Thomas, took his place as the pastor of the Metropolitan Tabernacle. Famous sayings of Charles Spurgeon:

|

©Copyright

We are happy for you to use any material found here, however, please acknowledge the source: www.gantshillurc.co.uk AuthorRev'd Martin Wheadon Archives

June 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed