|

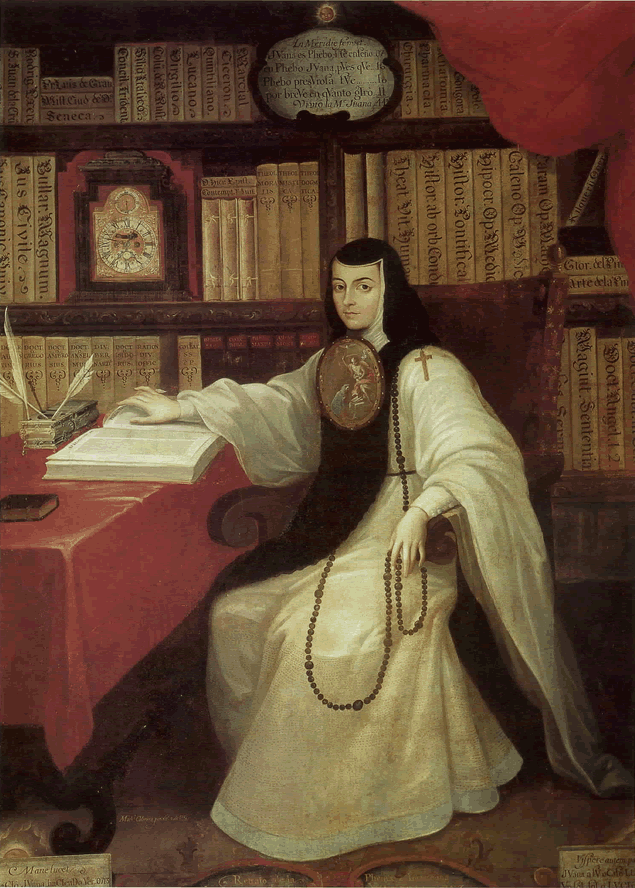

Juana Inés de Asbaje y Ramírez de Santillana was born on 12th November 1648 in the village of San Miguel Nepantla near Mexico City. Although she had older sisters, Juana was an illegitimate child because her parents never married. Her father, a Spanish captain called Pedro Manuel de Asbaje, abandoned the family shortly after Juana’s birth. Her mother was a Criolla woman called Isabel Ramírez. The Corillo people were Latin Americans with Spanish ancestors, which gave them more authority in Colonial Mexico, which belonged to the Spanish Empire. Juana’s father was Spanish, and her maternal grandparents were Spanish, thus making her a Criolla. Despite the lack of care from her biological father, Juana grew up in relative comfort on her maternal grandfather’s Hacienda, the Spanish equivalent of an estate. Her favourite place was the Hacienda chapel, where Juana hid with books stolen from her grandfather’s library. Girls were forbidden to read for leisure, but this did not prevent Juana from learning to read and write. At the age of three, Juana followed her sister to school and quickly learned how to read Latin. Allegedly, by the age of 5, Juana understood enough mathematics to write accounts, and at 8, wrote her first poem. By her teens, Juana knew enough to teach other children Latin and could also understand Nahuatl, an Aztec language spoken in central Mexico since the seventh century. It was unusual for those of Spanish descent to speak the native languages. The Spanish aimed to replace the Mexicano tongue with their Latin alphabet, so it was almost with defiance that Juana went out of her way to not only learn Nahuatl but compose poems in the language too. Juana finished school at 16 but wished to continue her studies at university. Unfortunately, only men could receive higher education. Juana spoke to her mother about her aspirations, suggesting she could disguise herself as a man to attend the university in Mexico City. Despite her pleading, Juana’s mother refused to allow her daughter to attempt such a risky plan. Instead, Isabel sent Juana to the colonial viceroy’s court to work as a lady-in-waiting. Under the guardianship of the viceroy’s wife, Leonor de Carreto (1616-73), Juana continued her studies in private. Yet, she could not keep her ambitions secret from her mistress, who informed the viceroy of Juana’s intelligence. Rather than reprimanding her, the viceroy Antonio Sebastián Álvarez de Toledo (1622-1715) took interest in Juana’s education. Wishing to test Juana’s intellect, the viceroy arranged a meeting of several theologians, philosophers, and poets and invited them to question the young girl. The men quizzed Juana on many topics, including science and literature, and she managed to impress them with her answers. They also admired how Juana conducted herself, and she remained unphased by the difficult questions they threw at her. News of the meeting spread throughout the viceregal court. No longer needing to hide her writing skills, Juana produced many poems and other writings that impressed all those who read them. Her literary accomplishments spread across the Kingdom of New Spain, which covered much of North America, northern parts of South America and several islands in the Pacific Ocean. Yet, female scholars and writers were an anomaly at the time, and rather than attract praise, Juana drew the attention of many suitors. After refusing many proposals of marriage, Juana felt desperate to escape from the domineering men. She wanted “to have no fixed occupation which might curtail [her] freedom to study.” The only safe place she could find where she could continue her work was the Monastery of St. Joseph, so she became a nun. Juana spent over a year with the Discalced Carmelite nuns as a postulant, then moved to the monastery of the Hieronymite nuns in 1669, preferring their more relaxed rules. The San Jerónimo Convent, which became Juana’s home for the rest of her life, was established in 1585 by Isabel de Barrios. Only four nuns lived in the building at first, but they soon grew in number, becoming one of the first convents of nuns of the Saint Jerome order. They based their role in life on the biblical scholar Saint Jerome (342-420), who translated most of the Bible into Latin. Known for his religious teachings, Jerome favoured women and identified how a woman devoted to Jesus should live her life. During his lifetime, Jerome knew many women who had taken a vow of virginity. He advised them on the clothing they should wear, how to conduct themselves in public, and what and how they should eat and drink. Despite taking on the title “Sor”, the Spanish equivalent of sister, Sor Juana’s main aim was to focus on her literary pursuits. Whilst she followed the ways of the Hieronymite nuns, she spent all her spare time writing. Juana’s previous employers, the Viceroy and Vicereine of New Spain became her patrons, helping her publish her work in colonial Mexico and Spain. Sor Juana also received support from the intellectual Don Carlos de Sigüenza y Góngora (1645-1700), who shared her religious beliefs as well as her passion for literature. Sigüenza, who claimed, “There is no pen that can rise to the eminence … of Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz,” also encouraged Juana to explore scientific topics. Sor Juana dedicated some of her works, particularly her poems, to her patrons. Those written for Vicereine Leonor de Carreto often featured the name Laura, a codename assigned by Juana. Another patron, Marchioness Maria Luisa Manrique de Lara y Gonzaga (1649-1721) was “Lysi”. Juana also wrote a comic play called Los empeños de una casa (House of Desires) for Doña Maria Luisa and her husband in celebration of the birthday of their first child, José. The first performance of Los empeños de una casa took place on 4th October 1683 and contains three songs in praise of Doña María Luisa Manrique: “Divine Lysi, Let Pass“, “Beautiful María” and “Tender Beautiful Flower Bud”. The protagonist, Doña Ana of Arellano, resembles the marchioness, who Sor Juana held in high regard. The play features two couples who are in love but cannot be together. Mistaken identities cause the characters much distress and the audience much hilarity. By the end of the final scene, everyone pairs up with the right partner, except one man who remains single as a punishment for causing the initial deception. In terms of theme and drama, Los empeños de una casa is a prime example of Mexican baroque theatre. Another play by Sor Juana premiered on 11th February 1689 to mark the inauguration of the viceroyalty Gaspar de la Cerda y Mendoza (1653-97). Sor Juana based Love is but a Labyrinth on the Greek mythological story of Theseus and the Minotaur. Theseus, the king and founder of Athens, fights against the half-bull, half-human Minotaur to save the Cretan princess Ariadne. Although Theseus resembled the archetypal baroque hero, Sor Juana portrayed him as a humble man rather than proud. Not all of Sor Juana’s writings were intended for public consumption. In 1690, Manuel Fernández de Santa Cruz (1637-99), the Bishop of Puebla, published Sor Juana’s critique of a sermon by the Jesuit priest Father António Vieira (1608-97). Titled Carta Atenagórica (Athenagorical Letter or a letter “worthy of Athena’s wisdom”), Juana expressed her dislike of the colonial system and her belief that religious doctrines are the product of human interpretation. She criticised Father António Vieira for his dramatic and philosophical representation of theological topics. Most importantly, Juana called the priest out for his anti-feminist attitude. Alongside Sor Juana’s critique, the Bishop of Puebla published a letter under the pseudonym Sor Filotea de la Cruz, in which he admonished the nun for her opinions. Ironically, the bishop agreed with many of Sor Juana’s thoughts, but he ended the letter by saying Sor Juana should concentrate on religious rather than secular studies. Whilst the critique focused on a religious sermon, Sor Juana included colonialism and politics in her argument, which the bishop felt were inappropriate topics for a woman, let alone a nun. Sor Juana responded to Sor Filotea, the Bishop of Puebla, in which she defended women’s rights to education and further study. Whilst she agreed that women should not neglect their duties, in her case her obedience to the Church and God, Juana pointed out that “One can perfectly well philosophise while cooking supper.” By this, she meant women could balance their education and everyday tasks. She jokingly followed this with the quip, “If Aristotle had cooked, much more would have been written.” In her response, Sor Juana quoted the Spanish nun St Teresa of Ávila (1515-82) as well as St Jerome and St Paul to back up her argument that “human arts and sciences” are necessary to understand sacred theology. She suggested if women were elected to positions of authority, they could educate other women, thus alleviating a male tutor’s fears of being in intimate settings with female students. The nun’s controversial response caused a lot of concern amongst high-ranking (male) officials who criticised her “waywardness”. They were angry with Sor Juana for challenging the patriarchal structure of the Catholic Church, and for claiming her writing was as good as historical and biblical texts. As a result, the San Jerónimo Convent forbid Juana from reading and sold her collection of over 4,000 books and scientific instruments for charity. With no one on her side, Sor Juana relented and agreed to renew her vows. The convent also required Juana to undergo penance, but rather than signing the penitential documents with her name, she wrote: “Yo, la Peor de Todas” (I, the worst of all women). From 1693 onwards, Sor Juana focused solely on her religious orders. Never again did she pick up a pen to write or a book to read. Instead, Juana spent her time either in prayer or tending the sick, which led to fatal consequences. After nursing other nuns stricken during a plague, Sor Juana fell ill and passed away on 17th April 1695. To read the full article, click here This blog post was published with the permission of the author, Hazel Stainer. www.hazelstainer.wordpress.com

0 Comments

The City of London is full of old buildings with historical connections, however, there are very few remains of the original construction of Londinium in AD43. Visible at Tower Hill station is the remains of the London wall that was built around about the year AD200; the majority of the buildings, on the other hand, would have been made with wood, therefore, no longer exist. Nonetheless, Tower Hill is home to some of London’s oldest buildings, for instance, the Tower of London, but there is one site that is 400 years older. Situated close to the original border of the London wall sits the oldest church in the city, All Hallows by the Tower. Part of the Diocese of London, this Anglican church is still open today for regular services and events, attracting international worshippers and tourists. Founded in AD675, this church predates all the places of worship in the city and has played a part in many significant historical events. The original wooden building founded by Erkenwald, Bishop of London, no longer exists, however, some sections of the first stone church on the site are still visible. All Hallows, named in honour of all the saints, both known and unknown, was established as a chapel of the abbey of Barking. Historical documents often refer to the church as All Hallows Barking or Berkyngechirche as a result of the connection. It is estimated that the first stone building was built circa AD900. Within the current building is an arch that has been dated back to the time of the Saxon and Viking invasions on Britain. Unlike most archways, this particular one – most likely the oldest surviving Saxon arch in London – has no keystone and was built using Roman floor tiles. Further evidence of the age of the original stone church was the discovery of a Saxon wheelhead cross during repair works after the Second World War. Beneath the church is an undercroft, which is also thought to date back to the original stone structure. This has been converted into the All Hallows Crypt Museum that tells the story of the church throughout history. It is free to enter and also contains a couple of chapels that are still regularly used today. The museum begins with evidence of the Roman occupation of Britain. This includes a section of tessellated flooring from the 2nd-century, situated at the bottom of the steps into the crypt. A small model of London, made in 1928, reveals what the city may have looked like in AD400 in comparison to the abundance of buildings that now run alongside the River Thames. In a case opposite the model is a range of artefacts that predate the church. These include Samian pottery, which would have been very expensive in that era, suggesting that the homes of wealthy families may have sat on the site before it was purchased by the abbey of Barking. As visitors progress through the museum, the timeline takes a sudden leap to the 1600s with a display of silver chalices, basins and medals that made up the Church Plate. These date from 1626 until the 20th century and show the influence the Tudor reformation had on the new Protestant church. The museum progresses through the history of the church until it reaches the first of two underground chapels. The Crypt Chapel or the Vicar’s Vault, as it is also known, contains the Columbarium of All Hallows. This was constructed in 1933 and is the resting place of the ashes of many people who have been associated with the church. During the excavations prior to building the chapel, many of the Roman fragments mentioned above were unearthed. Also discovered, and left where they were found, were three coffins dating from the Saxon era. The Crypt Chapel is still used for small services today, however, visitors to the museum are asked not to enter, only stand at the back and peer in at the altar on the opposite wall. This altar comes from Castle Athlit or Château Pèlerin in Palestine and has strong connections with the Knights Templar – the Templar cross can be seen carved into the stone frontal. Castle Athlit is thought to have been the last remaining Templar stronghold in the Holy Land during the crusades before being evacuated in 1291. The Knights Templar were a small band of noblemen founded in the 12th century during the First Crusade who pledged to protect pilgrims journeying to Jerusalem. Unfortunately, they also became money lenders and their wealth gave rise to corruption and jealousy. The altar in the crypt is not the only connection All Hallows has to these fearless warriors. In 1307, Pope Clement V (1264-1314) ordered the Templars to be restrained and their possessions seized. Edward II (1284-1327) was persuaded to allow the Inquisition judges to use All Hallows as one of the venues for the trials of the Templars. Fortunately, these trials were less violent than those held elsewhere. Next door to the Crypt Chapel is the Chapel of St Francis of Assisi where the Holy Sacrament is kept in a niche above the altar as a continual reminder of the presence of Jesus Christ. Originally a crypt dating from c1280, it became buried for several centuries, finally being rediscovered during excavation works in 1925. After careful refurbishment, it was opened two years later as a chapel and dedicated to St Francis. It is claimed that this chapel is one of the quietest places in the City of London. Visitors are invited to use the space for their private thoughts and prayers. Excluding the Saxon arch, the main sanctuary of All Hallows does not look as steeped in history as the crypts and chapels within its foundations. This is because the church has been victim to a number of historical events which caused damage to the architecture and surrounding area. The first recorded disaster occurred on 4th January 1650 when seven barrels of explosives caught fire in a house on Tower Street. Many of the buildings in the vicinity were destroyed and the church’s structure was damaged and every window blown out. Described as a “wofull accydent of Powder and Fyer,” 67 people were killed and many found themselves homeless. The following year, despite England being under the thumb of the Parliamentarians, permission was granted to rebuild the church. The church’s tower was named the Cromwellian Tower after the original Lord Protector of the Commonwealth. Yet, the door to the tower is known by another name: the Pepys Door. In 1666, a great fire ravished the streets of London, devouring hundreds of buildings. The flames worked their way down Tower Street, scorching the south side of the church but, thankfully, progressing no further. The tower of All Hallows remained safe from the blaze and it is from here, the diarist, Samuel Pepys (1633-1703) took in the sight of the devastation as he later recorded: “I up to the top of Berkeing Steeple, and there saw the saddest sight of desolation I ever saw. Everywhere great fires, the fire being as far as I could see … ” – Samuel Pepys, 1666 The greatest destruction All Hallows suffered transpired during the Second World War in December 1940. The church had survived all the events of the past centuries, however, in less than a minute, a great amount of history was destroyed forever. A firebomb landed on the church, flattening most of the main body of the building. By some miracle, the Cromwellian Tower remained standing, which, thankfully, sheltered the ancient Saxon arch beneath it. The vicar at the time, Tubby Clayton, was determined to rebuild the church and was supported by connections worldwide. Donations of money and building materials poured in and in July 1948, Queen Elizabeth, the wife of George VI, laid the foundation stone. A photograph of the occasion and the trowel she used can be seen in the crypt museum. The Australian born Reverend Philip Thomas Byard “Tubby” Clayton (1885-1972) was installed as the Vicar of All Hallows in 1922, however, he was already well-known in the Christian community. After his ordination in 1910, Clayton spent time as an army chaplain during the First World War. During this period, Clayton and fellow chaplain, Neville Talbot (1879-1943) set up a rest house for soldiers in Poperinge, Belgium. Officially called Talbot House but often referred to as Toc H, the international Christian establishment allowed soldiers of all ranks to spend their time on leave in a safe, friendly place. In a corner of All Hallows known as the Lady Chapel, a lamp sits on the altar tomb of Alderman John Croke (1477). This “Lamp of Maintenance” is a replica of the oil lamp that burnt in the top room of Talbot House during the First World War. Clayton and his work are also remembered by an effigy in the south aisle of the church. His ashes are interred in the Crypt Chapel. The architecture of the reconstructed church is not as grand as places of worship built in the past, however, it is a large, well lit, open space suitable for a number of different services. Although the majority of the structure was built after the Second World War, the inside houses items from a range of eras. The pulpit originally stood in St Swithin’s Church near Cannon Street and is similar to the one that sat in All Hallows in 1613. The sounding board above it, in the shape of a scallop shell, is a much more modern design. Like many other churches, the high altar sits in front of a mural of the Last Supper. This painting was produced by Brian Thomas in 1957 after the rebuilding of the church. It shows Christ blessing the bread surrounded by his apostles, however, on the right-hand side, Judas Iscariot is depicted leaving the room to betray Jesus to the Romans. The altar, apart from a cloth decorated with a phoenix-like bird, remains fairly bare – a cross would obscure the face of Jesus in the painting behind it. To the right of the high altar is an open plan chapel containing memorials of sailors and maritime organisations. Situated near the River Thames, All Hallows was popular with dock workers and their families; the Mariner’s Chapel honours the workers and sailors who lost their lives at sea. Windows along the south wall also contain memorials, such as for the seamen lost on HMS Hood. The crucifix above the altar in the chapel is made from the wood of the Cutty Sark and ivory from one of the Spanish Armada ships. There are other memorials around the church dating from Tudor times until the World Wars. Up above, and easily missed, is the Organ Loft containing an organ built for the reopening of the church in 1957. Hanging on the balcony is a set of arms that belonged to the Stuart king, Charles II. Due to its lengthy history, a number of famous names have become associated with All Hallows by the Tower. Miraculously preserved in a dry lead cistern, documents of births, weddings and events in Tower Hill record the names and dates of many who passed through the church, including a couple of well-known individuals. Handwritten on the baptismal register dated 23rd October 1644 is the entry “William, Son of William Penn & Margaret his wife of the Tower Liberties”. This baby boy, William Penn (1644-1718), would grow up to become an admiral, play a significant role protecting the church during the Great Fire of London, and, finally, move to America and found the state of Pennsylvania. Another American connection can be found in the marriage register under the date 26th July 1797. On this date, soon to be the sixth president of the USA, John Quincy Adams (1767-1848), was married to Louisa Catherine Johnson (1775-1852). Louisa was a local London girl and, until now, was the only First Lady to have been born outside the United States. All Hallows by the Tower is so steeped in history, it is impossible to list every connection. Many people and events are remembered through memorials, artefacts, windows and so forth around the church, and special services take place throughout the year. A medieval custom, Beating the Bounds, is observed yearly (this year on Ascension Day) and the Knolly Rose Ceremony, a symbolic event dating from 1381, is held every June. The church holds regular Sunday services beginning at 11am, which includes a sung communion. There are also a few services throughout the week, for instance, Morning Prayer and a Taizé service. As well as regular attendees, All Hallows attracts an international community and welcomes all visitors to the area. Free to enter and sheltered from the hustle and bustle of the capital, All Hallows by the Tower is worth a visit. Whether you come for religious purposes, to learn about the history of London or just out of curiosity, you are assured of a warm welcome. For the original article, click here This blog post was published with the permission of the author, Hazel Stainer. www.hazelstainer.wordpress.com

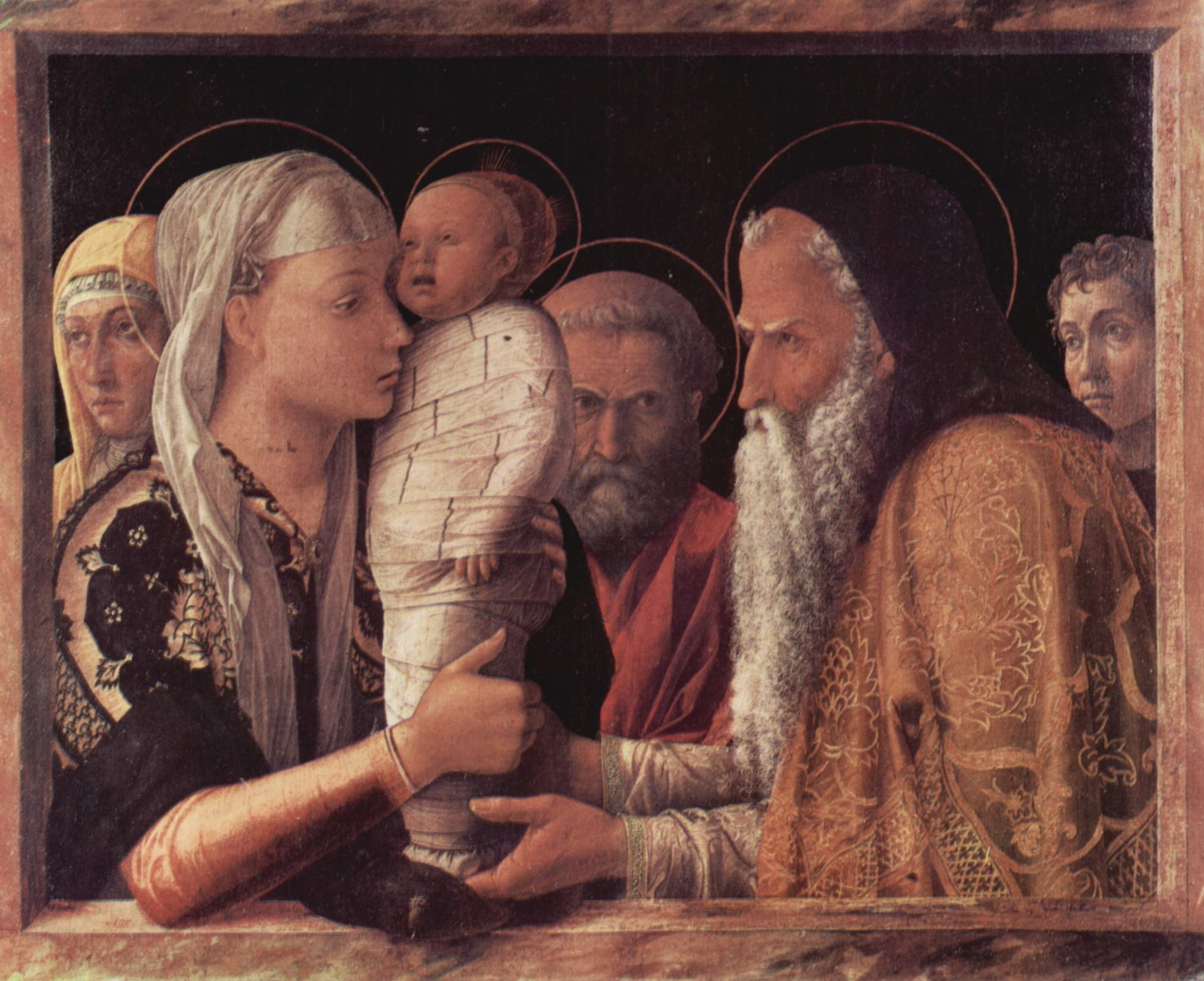

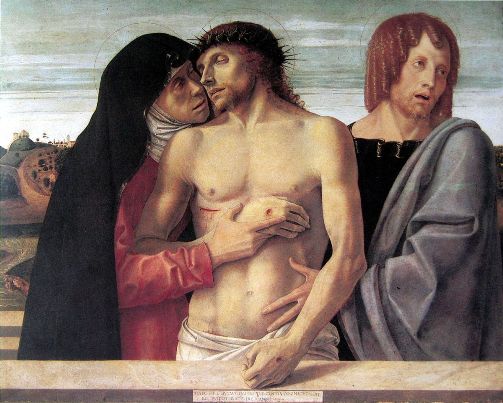

Andrea Mantegna and Giovanni Bellini are two of the greatest Italian painters of the Renaissance. Whilst it may appear the younger Bellini began his career by copying Mantegna, the already established artist, his work developed into groundbreaking paintings of which no one had seen the like before. The first and most obvious example of Mantegna’s influence on Bellini is their similar versions of The Presentation at the Temple. These show the moment Mary and Joseph present their child, Jesus at the Temple, forty days after his birth. Here, as recorded in the Gospel of Luke 2:22–40, they meet prophet Simeon and prophetess Anna. Both paintings show the Virgin Mary tenderly holding the tightly swaddled Christ Child while Simeon comes forward to take him. In the background between these main figures, Joseph watches the proceedings. In Mantegna’s version, which was painted shortly after his marriage, there are two figures stood either side of the painting. These are thought to be portraits of the artist himself and his wife, Nicolosia. The composition is rather claustrophobic, the framing being just enough room to hold the upper bodies of Mary and Simeon with their halos. Bellini’s version, however, is observed from further away, allowing room for an extra character on either side. It has not been officially determined who these people represent. To produce this piece, Bellini traced Mantegna’s original, which had been completed over ten years beforehand, keeping the poses, facial expressions and types of clothing almost exactly the same. The changes appear in the colours of the fabrics, the brightness of the scene and the lack of halos upon the Holy Family’s heads. To some, the paintings are so similar that Bellini’s version appears to be blatant plagiarism. On the other hand, there is enough difference to make it his own. It is as though Bellini is trying to say to Mantegna, “Look what I can do,” or perhaps even, “Anything you can do, I can do better!” The Presentation at the Temple also emphasises Mantegna’s influence on Bellini. Another is The Agony in the Garden, which Mantegna first produced at the end of the 1450s, inspiring Bellini to produce his own version at the beginning of the following decade. The paintings refer to chapter 14, verses 32-43 in the Gospel of Mark when Jesus prays in the Garden of Gethsemane while his disciples, Peter, James the Great and John the evangelist sleep. It is thought that Mantegna was initially inspired by a drawing by Jacopo Bellini. This Bible passage was an unusual choice to represent at this time since many Biblical paintings came in sets, representing the birth, life and resurrection of Christ; The Agony in the Garden was the first stand-alone religious painting in western art. Mantegna’s rocky terrain and sharp colours give the painting a harsh atmosphere and a portent of the events to come emphasised further by a dead tree and vulture on the right. A host of angels stand above on a cloud clutching Instruments of the Passion, another omen of Christ’s impending death. In the background is the city of Jerusalem from which a troop of soldiers follow Judas’ lead to arrest Jesus. Although Bellini took inspiration from Mantegna, on this occasion his outcome is not a copy of his brother-in-law’s. The events depicted remain the same, however, Bellini has introduced his own interpretation. Bellini chose to include only one ghostly angel standing aloft on a wispy cloud carrying a cup and plate as symbols of the approaching sacrifice. The colours and the way Bellini portrays light in his composition gives the painting a more tender feel. Unlike Mantegna’s version, it suggests hope, a hint of the resurrection, a sign of prayers being answered. Up until the 15th century, Biblical paintings showed the characters, Jesus, the Holy family and so forth as beautiful, angel-like beings. They were figures that personified the love of God and served as examples of the ideal human being. During Mantegna and Bellini’s careers, these notions began to change. Although traditional scenes of the nativity and the Madonna remained popular, artists began to change the way they portrayed the death of Christ. Instead of a peaceful, serene outcome, Mantegna and Bellini focused on painting the torture of Christ, revealing through him the sorrows of man. He was despised and rejected by mankind, a man of suffering, and familiar with pain. Like one from whom people hide their faces he was despised … – Isaiah 53:3 Unlike Mantegna, Bellini remained in Venice his whole life, often completing commissions in many Venetian and religious buildings. Despite being away from his brother-in-law, they remained in contact and had similar interests. Bellini was also interested in antiquity, finishing commissions Mantegna left incomplete after his death. At this time, however, the term antiquity also referred to events written in the Old Testament, such as the story of Noah. The Drunkenness of Noah was completed about a year before Bellini’s death and shows the daring and revolutionary ideas of the artist. Traditionally, Biblical paintings reveal positive stories and messages, however, this painting based on Genesis 9:20–23 reveals Noah’s vices rather than his virtuosity. Noah is lying naked on the floor in drunken slumber whilst his sons, Shem and Japheth, attempt to cover him with a red cloth. His third son, Ham, however, laughs at the sight of his father. Bellini also received commissions for portraits, however, he much preferred to paint portraits of characters rather than real people. The most beautiful of these is Virgin and Child with St. Catherine and Mary Magdalene which, unlike his other paintings with expressive landscapes, has a black background; the characters are lit from a light source outside of the frame. Although not overly elaborate or detailed, Virgin and Child with St. Catherine and Mary Magdalene attracts attention with its chiaroscuro effect and the glossy finish to the painting – an element that is lost looking at the image online or on paper. Mantegna’s medium of choice was egg tempera, which Bellini initially used before developing a preference for oil paints. Oils allowed for deeper colour and contrast in shading. There is no doubt that Mantegna and Bellini were two of the greatest painters in Italy during the 15th century, however, for an exhibition expressly about the pair, very little is alluded to about their lives, personalities or whether the brothers-in-law got on well together. This exhibition does not let Mantegna and Bellini’s personalities come through. It eliminates them in preference for detailed comparisons about how they painted and drew the same subjects, such as The Agony in the Garden and The Presentation at the Temple. Of course, it is interesting to see the similarities and difference between the two artists, but on leaving the exhibition, visitors remain none the wiser about who the two painters really were. Did they have happy lives and happy marriages? Do their paintings reflect their personalities? Did Mantegna mind Bellini copying his work? Were they rivals or is this a label art historians have assumed? So many questions … To read the full article, click here This blog post was published with the permission of the author, Hazel Stainer. www.hazelstainer.wordpress.com

Antwerp during the 17th-century was shaped by a large number of churches, however, during French Revolutionary rule, all but five monumental churches were destroyed. Unmissable from nearly every section of Antwerp’s Old Town is the enormous Roman Catholic Onze-Lieve-Vrouwekathedraal (Cathedral of Our Lady) whose 400 ft steeple towers over the surrounding buildings. It took labourers 169 years (1352-1521) to build the tallest cathedral in the Low Countries, comprising of a short and long tower, seven naves and numerous buttresses. The interior, however, is but a shadow of its 16th-century opulence having suffered a fire in 1533 and various destruction during the “Iconoclastic Fury” (1566) and Calvinist “purification” (1581-1585). Initially, on every pillar was a decorated altarpiece, however, only a handful survived. Thanks to the aid of Archduke Albert (1559-1621), the Infanta Isabella (1566-1633) and the Counter-Reformation, glory was restored to the cathedral and Rubens was commissioned by Nicolaas Rockox to paint a new altarpiece, Descent from the Cross (1611-14), which can still be seen in place today. The triptych depicts three Biblical scenes: the expectant Virgin Mary, Christ being lowered from the cross, and the elderly Simeon in the Temple. Other works by Rubens can also be found in the cathedral, for instance, Resurrection of Christ (1611-12) and Assumption of the Virgin (1625-26). Statues are also prevalent in the building, including two life-size limestone statues of Saints Peter and Paul designed by Johannes van Mildert (1588-1638) and a contemporary statue of burnished bronze, The Man Who Bears the Cross, which Jan Fabre (b.1958) produced in 2015. For a fee of €6, all this and more can be admired by the public. On the outskirts of the Old Town, just off the Mechelspleintje (Mechelen square) is the Neo-Gothic Sint-Joris Kerk (the Church of St George). Built in 1853, the church was a replacement for its 13th-century predecessor that had been destroyed by the French in 1798. Despite being tiny in comparison to the cathedral, the architect included two impressive towers approximately 50 metres in height, and a statue of Saint George on a triangular pediment. The interior of the church was mostly the work of Godfried Guffens (1823-1901) and Jan Swert (1820-79) who spent thirty years or so lavishly decorating the church with mural paintings. Mostly images of Jesus suffering on the cross, these symbolically represent the fight and hardships of the churches in Antwerp during the French Revolution. Visitors can see the large Merklin organ dated 1867, which has three keyboards and 1208 pipes. It reportedly has beautiful acoustics and remains to be one of the best-preserved concert instruments in the city. The organ sits in front of a large stained glass window, looked down upon by two musical saints, Saint Cecilia, the patroness of musicians and Saint Gregory. Located on the Hendrik Conscience square opposite the Erfgoedbibliotheek (Heritage Library) is the most important Baroque church in the Low Countries, Sint-Carolus Borromeuskerk (St Charles Borromeo’s Church). Consecrated in 1621, the church is a result of the Counter-Reformation, the Jesuit Order, and Antwerp’s number one painter, Rubens. The artist made considerable contributions to the facade, including the coat of arms featuring the “IHS” emblem of the Jesuits, and filled the interior with 39 ceiling paintings and three altarpieces. Alas, a fire in 1718 destroyed the original ceiling and the altarpieces were moved to the Habsburg imperial collection in Vienna. Today, a smaller altarpiece by Rubens, Return of the Holy Family, commissioned by Nicolaas Rockox is one of the highlights inside the church. From the balcony, visitors can look down upon the main body and altar. Two small altars can be found at either end of the balcony and, in the middle, visitors get a close up look of the huge organ. Sint-Jacobskerk (St James’s Church) on Lange Nieuwstraat is the place to go for fans of Rubens. Only a short walk from Rubens’ house, St James’s was his parish church, which he began attending before the building was completed. The first stone of the Gothic church was laid in 1491 and the last some 150 years later. As was the fate of all churches in the area, the interior of the church was destroyed by Calvinist iconoclasts in 1566 but, fortunately, Baroque decorations were found to replace the majority of the damaged altars. The high altar was sculpted in marble and wood by at least four artists and is thought to cost as much as 17,874 guilders, which was roughly seventy times the annual wage of a master craftsman. Being Rubens’ parish church, Sint-Jacobskerk is home to his resting place. One of the small, fairly modest chapels dedicated to the Virgin Mary, contains Rubens’ remains which lie under an altarpiece produced by his own hand. Rubens, a rather modest man himself, was offered the chapel as his burial ground whilst he was on his death bed. Rather than accepting the generous offer, he replied that he would only be buried there if his family believed he was worthy of such an honour. Naturally, his grave is now the biggest attraction at St James’s and there is a small fee required to gain entry to the church. The fifth and final church is Sint Pauluskerk (St Paul’s Church) a former Dominican church on the corner of Veemarkt and Zwartzustersstraat. Originally part of a large Dominican abbey, the church has a number of Baroque altars, over 200 statues and 50 paintings by artists such as Jacob Jordaens (1593-1678), Rubens, and Anthony van Dyck (1599–1641). Rubens was commissioned by the Dominicans to paint three large altarpieces and one of the fifteen paintings that make up the Rosary Cycle, Flagellation of Christ. Unfortunately, since the church building was not completed until 1634, Rubens never got to see his work in place because the altarpieces took many more years to finish and were, therefore, installed long after his death. Visitors are welcome to view the treasures belonging to the church, including a number of reliquaries, chalices, ceremonial robes, sculptures and ornaments. One reliquary is said to contain a thorn from the crown Jesus wore at his crucifixion. To read the full article, click here This blog post was published with the permission of the author, Hazel Stainer. www.hazelstainer.wordpress.com

This article comes from a review of an exhibition held at the Jewish Museum London in 2019. To read the full article, click here. Ironically, the exhibition includes scenes recorded in the New Testament, which is not part of the Jewish Bible. Nonetheless, certain events in the Gospels have played a major role in establishing the negative connection between Jews and money. “Then one of the Twelve—the one called Judas Iscariot—went to the chief priests and asked, “What are you willing to give me if I deliver him over to you?” So they counted out for him thirty pieces of silver. From then on Judas watched for an opportunity to hand him over.” – Matthew 26:14-16 (NIV) Judas Iscariot, the disciple who betrayed Jesus, has become the archetypal traitor and personification of the Jews. The Passion of Christ or the Easter story is well-known by the majority of the Western world regardless of religion. Judas’ involvement in the events leading up to Jesus’ crucifixion is perhaps not as recognised, however, his actions have permanently associated him with treachery and greed – something that managed to cast a shadow over the way Jews are perceived. In exchange for thirty silver coins, Judas Iscariot agreed to hand Jesus over to the Romans, thus allowing God’s plan to come to fruition. Despite being a small part in a much bigger story, Judas is often the man blamed for Jesus’ death. Depicted in artworks with red hair and wearing yellow, these colours have become icons of evil and deceit. The fact that the other Disciples were Jewish but had not betrayed Jesus is overshadowed by Judas’ treachery. A snap conclusion has been drawn that because Judas took the money and he was a Jew, then all Jews must be greedy. Whilst that statement can be seen as ridiculous, it managed to create an almost permanent judgment about Jews. In many artworks, Judas is portrayed with a money bag tied to his belt, suggesting his love of money, however, Rembrandt (1606-69) avoided this stereotypical imagery in his painting Judas Returning Thirty Pieces of Silver (1629). “Then Judas, which had betrayed him, when he saw that he was condemned, repented himself, and brought again the thirty pieces of silver to the chief priests and elders” – Matthew 27:3 Rembrandt’s painting shows the moment Judas attempts to return the money after he realises the extent of his actions. Judas kneels pleadingly on the floor, the thirty coins scattered at the feet of the priests and elders, who refuse to take the money back. Whilst his remorse is stronger than his desire to keep the money, some people point out that Rembrandt has painted Judas with his head turned towards the coins on the ground as though he still craves the money. Nevertheless, Judas, full of guilt and shame, hanged himself. “For I did dream of money bags tonight.” – Shylock, The Merchant of Venice The Jewish stereotype that stemmed from Judas was enhanced by William Shakespeare (1564-1616) in his play The Merchant of Venice. The play’s antagonist Shylock, is a Venetian Jewish moneylender who lends money to his Christian rival Antonio, setting the security at a pound of Antonio’s flesh. When Antonio cannot pay back the loan, Shylock demands his flesh. Throughout the play, Shylock’s appearance is stereotypical of the perception of Jews during the Elizabethan era. Jews had been expelled from England in 1290 and were not allowed to resettle in the country until Oliver Cromwell’s (1599-1658) rule, however, there were plenty of Jews in other countries, for instance, Venice, where the play is set. During the 16th and 17th century, Jews were often presented as a hideous caricature, usually with a hooked nose and bright red wig. Completing their costume, of course, was their ever-present money bag. Shylock’s forced conversion to Christianity at the end of the play is supposedly a happy ending, “saving” him from his unbelief and desire to kill Antonio. Overall, the play is typical of the antisemitic trends in Elizabethan England. ____________________________________ Jews, Money, Myth was an educational and eye-opening exhibition. Most people are aware of Jewish stereotypes and nearly everyone has learnt about the Holocaust, however, it is interesting to discover where and how these myths came about. Ultimately, the exhibition is challenging two particular tropes: “All Jews are rich,” and they “get rich at the expense of others.” Both statements are proved wrong and are only based upon a handful of Jews, for instance, the Rothschilds. This blog post was published with the permission of the author, Hazel Stainer. www.hazelstainer.wordpress.com

|

©Copyright

We are happy for you to use any material found here, however, please acknowledge the source: www.gantshillurc.co.uk AuthorRev'd Martin Wheadon Archives

June 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed