|

Before Ludovico Sforza (1452-1508) lost his position as Duke of Milan, he commissioned what would become one of Leonardo’s greatest works, second only, perhaps, to the Mona Lisa. Leonardo was tasked with painting a mural of The Last Supper onto the wall of the refectory of Santa Maria delle Grazie in Milan. This painting represents the Passover meal Jesus had with his apostles not long before his arrest as written in the Gospel of John.

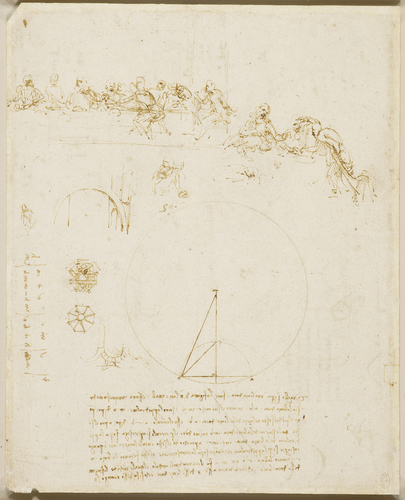

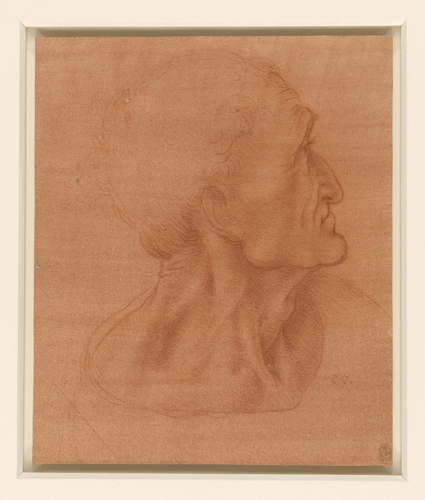

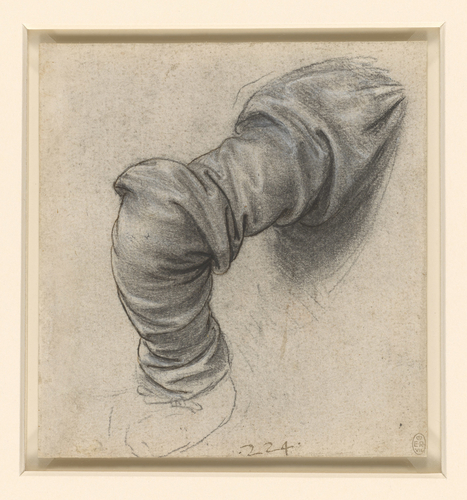

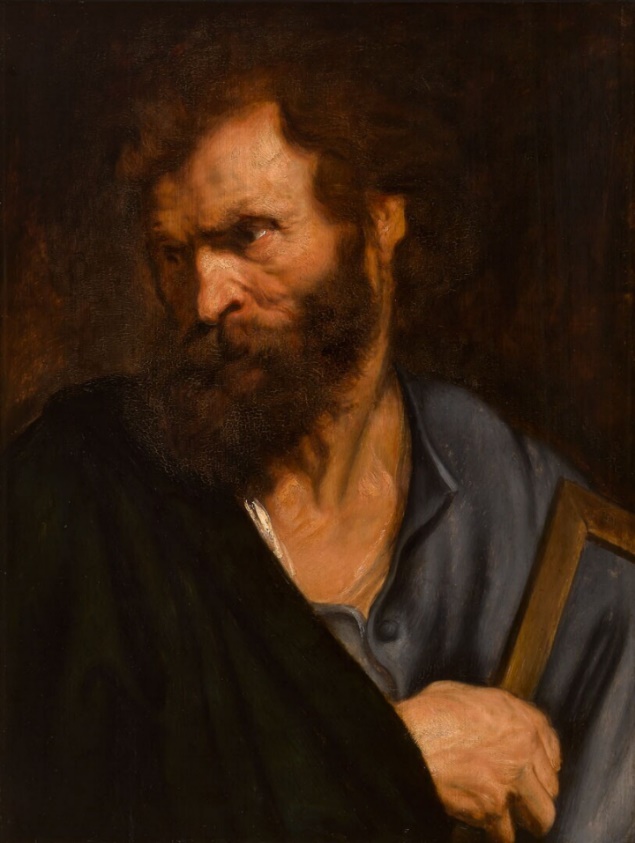

After he had said this, Jesus was troubled in spirit and testified, “Very truly I tell you, one of you is going to betray me.”- John 13:21 (NIV) It is thought that Leonardo produced hundreds of sketches, refining his ideas for the final painting, however, only a few survive. Only one compositional sketch remains, showing a couple of ideas he experimented with. The challenge was to fit thirteen figures around a table whilst giving each one a distinctive characteristic. In one sketch, Judas is depicted at the end of the table and in another, he is standing to receive the bread from Christ. In the final painting, Judas has been integrated into the group of disciples. Leonardo’s initial sketches include some of the disciples, one of which is Judas. The traitor has a hooked nose, close-set lips and a muscular neck. His head is turned away from the viewer to look at Christ in mild surprise. In the painting, Judas’ facial expression appears to reveal his evil intent, however, it is thought this has been added by restorers at a later date. The sketch of St Philip shows the disciple’s youth, emphasised by his long wavy hair and smooth face. St James also appears to be young with a similar hairstyle. The latter sketch, however, has been produced more rapidly than the others, suggesting it was drawn from a live model. Leonardo also practised the drapes of the clothing the disciples wore, for example, the sketch of St Peter’s arm who, dressed in thick fabric, leans over Judas’ shoulder in the final painting. Read more here

0 Comments

Finally, we reach the thirteenth disciple – yes, you read that right. According to the Acts of the Apostle, written between 80 and 90 AD, the Apostles chose someone to replace Judas Iscariot. Matthias is different from the other disciples in that Jesus, who had already ascended into heaven, did not choose him.

In Acts 1, Peter announced to the other disciples, “It is necessary to choose one of the men who have been with us the whole time the Lord Jesus was living among us, beginning from John’s baptism to the time when Jesus was taken up from us.” (1:21-22) Two men were nominated: Joseph Barsabbas, also known as Justus, and Matthias. Lots were drawn and Matthias was added to the eleven apostles. Nothing else is found about Matthias in the canonical New Testament, however, it can be inferred that Matthias had been a follower of Jesus for the past few years. Nonetheless, non-canonical documents report that Matthias, like the other disciples, travelled from place to place, preaching the Gospel. Traditionally, Matthias is associated with the arrival of Christianity in Cappadocia and the countries bordering the Caspian Sea. According to the 14th-century Greek ecclesiastical historian, Nicephorus Callistus Xanthopulus, Matthias began preaching in his home region of Judea before travelling to modern-day Georgia, where he was stoned to death. A marker within the ruins of a Roman fortress claims Matthias was buried there. Other sources record Matthias preaching in Ethiopia. The Coptic book Acts of Andrew and Matthias claims the disciples were “in the city of the cannibals in Aethiopia.” The Synopsis of Dorotheus corroborates this, saying, "Matthias preached the Gospel to barbarians and meat-eaters in the interior of Ethiopia, where the sea harbour of Hyssus is, at the mouth of the river Phasis. He died at Sebastopolis, and was buried there, near the Temple of the Sun." Sebastopolis is in modern-day Turkey, therefore, this statement goes against the theory that Matthias died in Georgia. A third theory suggests Matthias was stoned in Jerusalem, perhaps taking on Judas’ punishment, and then beheaded. On the other hand, Hippolytus of Rome believed Matthias died of old age. Fragments survive of the apocryphal Gospel of Matthias, which suggests Matthias believed in a life of abstinence. “We must combat our flesh, set no value upon it, and concede to it nothing that can flatter it, but rather increase the growth of our soul by faith and knowledge.” Similar to the other disciples, minus Judas, Matthias was venerated by the Roman Church in the 11th Century. He was given the 24th February as his feast day (25th in Leap Years); however, this was later changed to 14th May so that it would not coincide with Lent. Legend claims Empress Helena, the mother of Constantine the Great, brought Matthias’ remains to Italy where they were interred in the Abbey of Santa Giustina, Padua, with some being sent to the Abbey of Matthias in Germany. This, however, goes against the claim that Matthias is buried in Georgia. Just for fun, these are the things that claim Matthias as their patron saint:

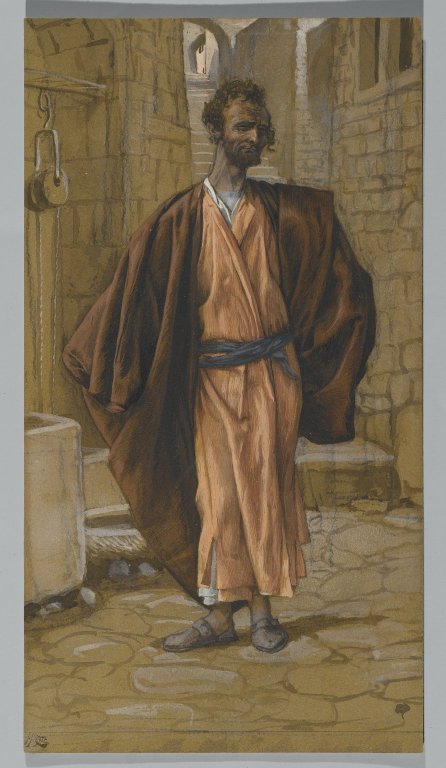

Judas Iscariot, the most infamous of the Twelve Disciples, betrayed Jesus to the Sanhedrin in the Garden of Gethsemane, which led to Jesus’ death and crucifixion. Due to this notorious role, Judas is a controversial figure in the Bible. One the one hand, he betrayed Jesus, and on the other, he set in motion the events that led to the resurrection, which was necessary to bring salvation to humanity.

The name Judas was a Greek version of the Hebrew name Judah and, therefore, was popular in Biblical times. We have already looked at the disciple Jude, who was also known as Judas Thaddeus. To distinguish between the two disciples, the Gospel writers used Epithets, such as “Judas, son of James” for Jude and “Iscariot” for Judas. It is not completely certain what “Iscariot” meant, however, some scholars have linked it to a Hebrew phrase meaning "the man from Kerioth.” Other suggestions for the meaning of “Iscariot” are “liar”, “red colour”, and “to deliver”. There is also the theory Judas was connected with the Sicarii group who carried daggers under their cloaks, however, there is no evidence they were around during Judas’ lifetime. “Kerioth Hezron (that is, Hazor)” (Joshua 15:25) was a town in the south of Judea. Judas may have been born there but there is no direct reference to this in the Bible. All we know about Judas’ life before he met Jesus is his father’s name. “Judas, the son of Simon Iscariot, who, though one of the Twelve, was later to betray him.” (John 6:71) Judas Iscariot features in all four Gospels, although not always named. In Matthew, Mark and Luke, Jesus sent out the Twelve in pairs to preach and gave them authority over impure spirits. Other than the twelve, most of Jesus’ disciples had been unable to accept his teachings, which is why they are not named in the Bible. In the Gospel of John, Jesus emphasised that he had chosen the Twelve deliberately, because he knew he could rely on them, however, he also shocked them by saying, “Have I not chosen you, the Twelve? Yet one of you is a devil!” (John 6:70) The “devil” we know refers to Judas Iscariot. Despite Jesus knowing Judas would eventually betray him, he promised all the disciples, “Truly I tell you, at the renewal of all things, when the Son of Man sits on his glorious throne, you who have followed me will also sit on twelve thrones, judging the twelve tribes of Israel.” (Matthew 19:28) This suggests Judas had been chosen specifically for the role he would play in the crucifixion and resurrection and would not be punished by God. Judas’ act of betrayal is portrayed from different angles in each Gospel. In Matthew, we are told that Judas Iscariot went to the chief priests and asked, “What are you willing to give me if I deliver him over to you?” (Matthew 26:15) The priests gave Judas thirty pieces of silver. The Gospel of Mark also says the chief priests promised to give Judas money for handing over Jesus, however, Mark does not indicate how much. After the Last Supper, Judas found the opportunity to hand Jesus to the chief priests. Whilst Jesus was praying in the Garden of Gethsemane, Judas arrived with a large, armed crowd and said, “The one I kiss is the man; arrest him.” (Matthew 26:48) The Gospel of Luke provides a similar account to Matthew and Mark, however, Luke includes a further detail. Luke suggests Judas did not go to see the chief priests of his own free will but says, “Satan entered Judas, called Iscariot, one of the Twelve.” (Luke 22:3) The Gospel of John is the only Gospel that does not state Judas betrayed Jesus in return for money. Nonetheless, it is implied Judas was greedy and a thief, therefore, it is likely Judas would have asked the priests for something in return for delivering Jesus to them. “He did not say this because he cared about the poor but because he was a thief; as keeper of the money bag, he used to help himself to what was put into it.” (John 12:6) John also directly indicates that Judas would be the one to betray Jesus. In the Synoptic Gospels, Jesus tells his disciples at the Last Supper that one of them would betray him. In the Gospel of John, however, he makes it more obvious whom this disciple is by saying, “‘It is the one to whom I will give this piece of bread when I have dipped it in the dish.’ Then, dipping the piece of bread, he gave it to Judas, the son of Simon Iscariot. As soon as Judas took the bread, Satan entered into him.” (John 13:26-27) Jesus then told Judas to go and do what he had to do quickly, however, the other disciples were unaware of what this meant. “Since Judas had charge of the money, some thought Jesus was telling him to buy what was needed for the festival, or to give something to the poor.” (John 13:29) Judas’ betrayal is unusual in that it gets mentioned in all four Gospels. The other eleven disciples are either involved with events recorded in a couple of the Gospels, or they are barely mentioned at all. The New Testament scholar Bart D. Ehrman (b.1955) states this is evidence that Judas’ actions truly happened. Whilst Christians believe everything in the Gospels are fact, it is strange not every Gospel writer thought certain events were worth writing about. It is generally believed Judas was overcome by remorse after the arrest of Jesus and committed suicide. The Gospel of Matthew records Judas tried to return the thirty pieces of silver to the chief priests, saying, “I have sinned, for I have betrayed innocent blood.” (Matthew 27:3) The chief priests, would not accept the coins, “So Judas threw the money into the temple and left. Then he went away and hanged himself.” (Matthew 27:5) The chief priests could not accept the money back because it was “blood money.” Therefore, they used the money to buy a plot of land where foreigners (non-Jews) could be buried. “That is why it has been called the Field of Blood to this day.” (Matthew 27:8) This supposedly fulfilled the prophecy of Jeremiah: “They took the thirty pieces of silver, the price set on him by the people of Israel, and they used them to buy the potter’s field, as the Lord commanded me.” (Matthew 27:9-10) Yet, there is no such prophecy in the Book of Jeremiah, however, there is in Zechariah. The Book of Acts, on the other hand, claims Judas bought the field with the money. “With the payment he received for his wickedness, Judas bought a field; there he fell headlong, his body burst open and all his intestines spilled out. Everyone in Jerusalem heard about this, so they called that field in their language Akeldama, that is, Field of Blood.” (Acts 1:18-19) In this verse, there is no suggestion that Judas was remorseful and his death could have been an accident rather than suicide. The two differing accounts of Judas’ death have caused consternation amongst scholars. St. Augustine of Hippo suggested the account in Acts was a continuation of Matthew. The field bought by the chief priests with Judas’ money may have been the same field in which Judas hanged himself. The rope may have eventually broken, causing his body to burst open on impact with the ground. Other writers have suggested the version in Acts was metaphorical rather than factual; "falling prostrate" was Judas in anguish and the "bursting out of the bowels" is pouring out emotion. A couple of Apocryphal books add more to the account of Judas’ death. The Gospel of Nicodemus, written in the 4th century AD, relates that Judas went home to his wife and told her he was going to kill himself because he knew Jesus would punish him after the resurrection. His wife laughed and said Jesus is as unlikely to rise from the dead than the chicken carcass she was preparing for dinner. At that very moment, the chicken was restored to life. The Gospel of Judas, on the other hand, reveals Judas’ worries that the other disciples would persecute him, so he preferred to commit suicide than face that fate. Just as the term “Doubting Thomas” has entered common language, the name “Judas” has come to mean “betrayer” or “traitor”. In Spain, Judas is usually depicted with red hair, which during the renaissance era was regarded as a negative trait. As a result, red hair, alongside greed, became a way of portraying Jewish people in literature. In traditional art, Judas is often portrayed with a dark-coloured halo, which contrasts with the lighter colour of the other disciples. Unlike the other disciples, Judas was not made a saint. Saint Matthias quickly filled his place among the twelve disciples. Nevertheless, Judas will not be forgotten. His betrayal is remembered annually in churches across the world. Judas has also become a fascination with authors and playwrights. Just for fun, here are a few books, films and plays you may enjoy involving the Apostle Judas Iscariot:

Simon the Zealot or Simon the Canaanite/Cananaean is possibly the most obscure of the disciples. Although his name appears on a list of the disciples mentioned in the Gospels of Matthew, Mark and John and the Book of Acts, he does not play a named role elsewhere.

To distinguish Simon from Simon Peter, Matthew and Mark use the term “Simon the Canaanite” (Matthew 10:4; Mark 3:18 KJV). Luke and Acts, on the other hand, calls him “Simon Zelotes” (Luke 6:15; Acts 1:13 KJV) or “Simon the Zealot” (NIV) depending on the translation. The term “Canaanite” has led people to assume Simon was from Canaan or Cana, however, the Hebrew text proves this to be a mistranslation. In Hebrew, Simon was referred to as “qanai”, which means “zealous”. The reason for the Canaanite confusion is easy to forgive since the term stems from the same Hebrew word. Unfortunately, no one knows why Simon was singled out as being zealous. Although, in contemporary English zealous means enthusiastic or having a strong passion, in Greek, it was also a synonym for jealous. Catholic scholars have attempted to identify Simon the Zealot with both Simon the brother of Jesus and Simeon of Jerusalem, although there is no evidence in the Bible for either claim. The names of Jesus’ brothers are mentioned in Mark 6:3 “Is not this the carpenter, the son of Mary and brother of James and Joses and Judas and Simon, and are not his sisters here with us?” Simeon of Jerusalem or Saint Simeon, however, does not appear in the Bible. According to tradition, Saint Simeon was the second Bishop of Jerusalem who was appointed by the Apostles Peter, James and John. He is also said to be the son of Clopas and, therefore, potentially a cousin of Jesus. “Near the cross of Jesus stood his mother, his mother's sister, Mary the wife of Clopas, and Mary Magdalene.” (John 19:25) As you may recall from my previous article, the “Judas” mentioned in Mark 6:3 may have been the disciple Jude, also known as Judas Thaddeus, and the “James” was potentially James the Less. So, it is possible, as it says in the Golden Legend compiled by Jacobus de Varagine (1230-1299), "Simon the Cananaean and Judas Thaddeus were brethren of James the Less and sons of Mary Cleophas, which was married to Alpheus." The names Clopas and Cleophas refer to the same person depending on the Bible translation. The Bible does not record how Simon was called to be a disciple, however, a book of the Apocrypha, if it is to be believed, might shed some light on this. The Syriac Infancy Gospel, which supposedly records the childhood of Jesus, contains a story about a boy named Simon who was bitten by a snake. Jesus, who was only a child himself, healed the boy and said, "you shall be my disciple." The story is concluded with "this is Simon the Cananite, of whom mention is made in the Gospel." There are various speculations about Simon’s actions after Jesus’ death and resurrection. Some say he visited the Middle East and Africa. Another tradition claims he visited Roman Britain during the Boadicea’s rebellion in 60 AD. Likewise, there is more than one version of his death. Stories relate Simon being crucified in Samaria, sawn in half in Persia, martyred in Iberia, crucified in Lincolnshire and dying peacefully in Edessa. Traditionally, in art, Simon is portrayed with a saw, suggesting he was sawn in half. Simon the Zealot, like all the apostles, is regarded as a saint and shares a feast day with Saint Jude: 28th October. He is the patron saint of curriers, sawyers and tanners, perhaps alluding to his profession. Just for fun, here are some of the attributes he appears with in artworks:

Jude, Judas Thaddaeus, Thaddeus, Jude of James, Lebbaeus, or whatever you wish to call him, was an apostle and martyr from 1st century Galilee. The use of multiple names in the Bible makes it difficult to determine whether they are one person or several. Cross-referencing the four Gospels, most scholars have agreed that the Thaddaeus in Matthew and Mark is the same person as Judas in Luke and John. Matthew also refers to the apostle as Lebbaeus and Judas the Zealot, whereas Luke and the Acts of the Apostles record him as Judas, son of James. One certain thing, however, is this disciple should not be confused with Judas Iscariot, the betrayer of Jesus.

Not including Judas Iscariot, the name Judas or Jude is mentioned six times in the Bible. In Luke, both Judas son of James and Judas Iscariot are recorded in a list of the twelve disciples. The same is recorded in Acts, minus the latter, of course. Similar lists in Matthew and Mark, on the other hand, state his name as Thaddeus. It has been suggested this may have been a nickname. Thaddeus means “courageous of heart”. John makes an effort to differentiate between the similarly named disciples. “Then Judas (not Judas Iscariot) said, ‘But, Lord, why do you intend to show yourself to us and not to the world?’” (John 14:22) In response to this, Jesus says, “Anyone who loves me will obey my teaching. My Father will love them, and we will come to them and make our home with them. Anyone who does not love me will not obey my teaching. These words you hear are not my own; they belong to the Father who sent me… Peace I leave with you; my peace I give you. I do not give to you as the world gives. Do not let your hearts be troubled and do not be afraid.” (14:23-24, 27) There is debate as to whether Judas was the brother of Jesus, since Matthew 13:55 says, “Isn’t this the carpenter’s son? Isn’t his mother’s name Mary, and aren’t his brothers James, Joseph, Simon and Judas?” The same is said in the Gospel of Mark but there is no clarification as to whether this Judas was also the disciple. Protestant churches tend to believe they were different people, whereas Catholics usually argue the opposite. The author of the Book of Jude is also widely debated. The book begins with the author’s introduction: “Jude, a servant of Jesus Christ and a brother of James.” (Jude 1:1) We know from Matthew that both Judas and James were brothers of Jesus, but is Jude the same person? Also, we know Judas was the name of a disciple of Jesus, and therefore may identify himself as “a servant of Jesus Christ.” From this, it could be inferred that Judas/Thaddaeus, Judas the brother of Jesus and Jude the author are all one person, however, no one has been able to find solid proof. A collection of biographies compiled by Jacobus de Varagine in the 13th-century attempts to clarify the mixture of names used in the Gospels:

Jude’s life before becoming a disciple is unknown, however, over time, theories and ideas suggest he may have been a farmer by trade. Growing up in Galilee, Jude would probably have spoken both Greek and Aramaic, which would have come in useful when preaching to people of other areas. The 14th-century historian Nicephorus Callistus believed Jude was the bridegroom at the wedding at Cana recorded in the Gospel of John. This was the event that saw Jesus perform his first miracle. Tradition states Jude was martyred around 65 AD in Beirut. Although Beirut is now the capital of Lebanon, it was then part of the Roman Province of Syria. Abdias, the first bishop of Babylon, recorded Jude’s death in the Acts of Simon and Jude along with the death of fellow disciple, Simon the Zealot. It is thought the pair was killed with an axe, possibly beheaded. Many years after his death, Jude’s bones were brought to Rome where they were buried in the crypt of St Peter’s Basilica. His resting place became a popular destination for pilgrims, giving him the title “The Saint for the Hopeless and the Despaired”. He is also known as “The Patron Saint of the Impossible.” Shrines and churches have been erected all over the world in Jude’s honour. These can be found in Australia, Brazil, Sri Lanka, Cuba, India, Iran, the Philippines, New Zealand, the United Kingdom, the United States and Lebanon. The most recent shrine is the National Shrine of Saint Jude in Faversham, Kent, which was built in 1955. The Feast of St Jude is traditionally celebrated on 28th October. Just for fun, here is a list of the things and places that have Jude as their patron:

James, son of Alpheus – not to be confused with James, son of Zebedee – is a disciple that is mentioned in three of the four gospels: Matthew, Mark and Luke. In the Church, he is also identified as James the Less, the Minor, or the Younger depending on the translation. “Some women were watching from a distance. Among them were Mary Magdalene, Mary the mother of James the younger and of Joseph, and Salome.” (Mark 15:40 NIV)

The word “less” does not imply James was less worthy than James the Greater. Instead, it may refer to his age or his height. Although there are very few mentions of James the Less in the Bible, his importance is equal to that of the other disciples. “Truly I tell you, at the renewal of all things, when the Son of Man sits on his glorious throne, you who have followed me will also sit on twelve thrones, judging the twelve tribes of Israel.” (Matthew 19:28) Like most of the other disciples, James came from Galilee, which at the time was part of the Roman Empire. How he came to be chosen as Jesus’ disciple is missing from the Bible. There is also confusion about who James was since some scholars debate he may also have been Jesus’ brother, James the Just. The consensus, however, is they were two separate people. Sadly, very little is known about James. After King Herod killed James the Greater, Peter who had been arrested escaped and said to Mary the mother of John, “Tell James and the other brothers and sisters about this.” (Acts 12:17) Since James the Greater was dead, this James could either be James the Less or James the Just. Unfortunately, there is no clarification in the Bible. James the Less’s death was recorded by the 2nd-century theologian Hippolytus. “And James the son of Alphaeus, when preaching in Jerusalem was stoned to death by the Jews, and was buried there beside the temple.” James the Just, the brother of Jesus, is also believed to have died the same way, thus adding to the confusion about their identity. On the other hand, James the Less is traditionally believed to have preached at Ostrakine in Lower Egypt. Many believe he was crucified there. In Art, James is usually depicted with a fuller’s club, implying he may have been involved with woollen clothmaking before he became an apostle. Occasionally, he is depicted with a carpenter’s saw, suggesting an alternative trade. Just for fun, here are the items that have Saint James the Less as their patron. Some, you will notice, are related to clothmaking and others to medicine – another potential career, perhaps?

Matthew, later Saint Matthew, is another of the Galilean disciples. Traditionally, he is also the author of the Gospel of Matthew, one of the four evangelists. Of all the disciples, he is one of the least likely candidates to have been chosen by Jesus since he was “Matthew the tax collector” (Matthew 10:30) and not liked by the public.

Tax collectors or publicans, as they were also called, collected unpaid taxes for the Roman occupiers. It was not their job that caused people to dislike them but rather their fraudulent behaviour. Rather than collecting the amount that was owed, the tax collectors demanded more money, keeping the excess for themselves. Tax collectors were seen as both greedy and collaborators with the Romans. “As Jesus went on from there, he saw a man named Matthew sitting at the tax collector’s booth. “Follow me,” he told him, and Matthew got up and followed him.” (Matthew 9:9) Jesus came across Matthew after healing a paralysed man in Capernaum. Matthew invited Jesus to his house for a meal, an invitation that did not go unnoticed by the Pharisees. Always trying to find fault with Jesus, the Pharisees asked the disciples “Why does your teacher eat with tax collectors and sinners?” (9:11) Before they could respond, Jesus answered them, explaining, “It is not the healthy who need a doctor, but the sick. But go and learn what this means: ‘I desire mercy, not sacrifice.’For I have not come to call the righteous, but sinners.” (9:12-13) Nothing is known of Matthew’s early life other than his career, although in one Bible verse the name of his father is mentioned. “And as he passed by, he saw Levi the son of Alphaeus sitting at the receipt of custom, and said unto him, Follow me. And he arose and followed him.” (Mark 2:14) As you will notice, Matthew was also known by the name Levi and his father was Alphaeus. The Bible also records the father of the Apostle James (see my next article) as Alphaeus but there is no evidence they are the same person. A man of the same name is also implied to be the father of Joseph/Joses, a potential brother of Jesus. In the Catholic Church, Saints Abercius and Helena also have a father called Alphaeus. Matthew’s call to discipleship is recorded in the gospels of Matthew, Mark and Luke, however, he is never mentioned in John. The final mention of the disciple is in Acts 1:10–14 where the apostles had withdrawn to a room after the Ascension of Jesus. To begin with, the disciples remained in the Jewish communities in Judea, preaching the Gospel before moving to other countries. Unfortunately, scholars have not been able to determine to which countries Matthew travelled. It is traditionally believed he died a martyr but there is no evidence of this. Writers have suggested Hierapolis in Greece or Ethiopia as Matthew’s place of death. The early Christian bishop Papias of Hierapolis (c. AD 60–163) was the first person to propose Matthew the Apostle and Matthew the Evangelist were the same. The Gospel was written in Hebrew near Jerusalem for Hebrew Christians before being translated into Greek. As a tax collector, Matthew would have been literate in Aramaic and Greek as well as his native tongue. To begin with, Matthew’s Gospel was known as Gospel according to the Hebrews and Gospel of the Apostles. An argument against Matthew’s authorship points out the text was written anonymously and at no point does the author imply he was an eyewitness to the events. Matthew is supposedly buried in the crypt of Salerno Cathedral in southern Italy. He is recognised as a saint in Catholic, Orthodox, Lutheran and Anglican churches, and his feast day is celebrated on 21st September. In art, Matthew is usually shown with a book, implying he wrote the Gospel, and an angel. Just for fun and to end this article, here is a short list of the things that have Matthew as their patron:

Thomas, most commonly known as “Doubting Thomas” is one of the disciples with a speaking part in the Bible, and yet, he is barely mentioned in the Synoptic Gospels. Matthew 10:3, Mark 3:18 and Luke 6:15 list him as one of the twelve disciples but nothing is mentioned about how he became an apostle and what came after. For that, we have to turn to the Gospel of John.

Thomas is believed to have come from Galilee, however, he is listed as having two names. Thomas was his Aramaic name and Didymus was his Greek name, both of which mean “twin”. Although there is no explanation for the choice of names, it is most likely Thomas was born a twin. In the non-canonical Gospel of Thomas, the author gives his name as Judas Thomas. The first time Thomas’ name appears in John’s Gospel is John 11:16: “Then Thomas (also known as Didymus) said to the rest of the disciples, ‘Let us also go, that we may die with him.’” Jesus had learnt that his friend Lazarus was sick and had decided to visit him. The disciples were shocked by this decision because Lazarus lived in Judea where the Jewish population had tried to stone him. Yet, Jesus was adamant and Thomas encouraged the disciples to go with him. Thomas next speaks in John 14:5: “Thomas said to him, ‘Lord, we don’t know where you are going, so how can we know the way?’” Jesus had explained that he was going to prepare a place for them in heaven and that one day they would join him there. Thomas spoke on behalf of the disciples, explaining that they did not know where that place was or how to get there. Jesus responded to this with one of the most famous sayings in the bible: “I am the way and the truth and the life. No one comes to the Father except through me.” (14:6) Of course, the most famous exchange between Thomas and Jesus takes place after the resurrection. This is the scene that forever brands him as “Doubting Thomas.” “Now Thomas (also known as Didymus), one of the Twelve, was not with the disciples when Jesus came.” (John 20:24) To prove he had risen from the dead, Jesus visited the disciples in a locked room where they were hiding from the Jewish leaders, however, Thomas was not there. Unable to imagine someone coming back to life, Thomas doubted the disciples’ claim that they had seen the Lord. “Unless I see the nail marks in his hands and put my finger where the nails were, and put my hand into his side, I will not believe.” (20:25) The following week, Jesus visited the disciples again. This time, Thomas was with them and Jesus showed Thomas the nail marks and wound in his side. At once, Thomas believed, declaring “My Lord and my God!” (John 20:28) Unfortunately, it was too late for Thomas to redeem himself and he is still referred to as the doubter, giving his name to sceptics who refuse to believe without direct personal experience. “Jesus told him, ‘Because you have seen me, you have believed; blessed are those who have not seen and yet have believed.’” (20:29) Apart from these brief episodes in the Gospel of John, the Bible reveals nothing else about Thomas’ life. Scholars have turned to other literature to ascertain what happened to Thomas after Jesus was taken up into heaven. One belief is Thomas travelled to India in AD 52 to spread the Christian faith to the Jewish community that lived there at the time. Tradition claims he established seven churches while he was there and baptised many families. The theologian Origen of Alexandria (184-253) stated Thomas was the apostle to the Parthians, a historical region located in north-eastern Iran. Eusebius of Caesarea (c.260-340) recorded Thomas and Bartholomew were assigned to Parthia and India, and the Christian treatise Didascalia Apostolorum corroborates Thomas’ presence: "India and all countries considering it, even to the farthest seas... received the apostolic ordinances from Judas Thomas, who was a guide and ruler in the church which he built." Traditions of the Saint Thomas Church in India claim Thomas briefly visited China. In the Office of St. Thomas for the Second Nocturn written by Gaza of the Church of St. Thomas of Malabar, the following is claimed:

Saint Thomas has only been made patron of a handful of things, including India and Sri Lanka. Just for fun, here are a few fun “facts” about the apostle:

The next disciple in our series is Bartholomew, who became a disciple at the same time as Philip. Although he is named Bartholomew in the Gospels of Matthew, Mark and Luke, John’s Gospel refers to him as Nathanael. “Philip found Nathanael and told him, ‘We have found the one Moses wrote about in the Law, and about whom the prophets also wrote—Jesus of Nazareth, the son of Joseph.’” (John 1:45) Little is known about Bartholomew/Nathanael, however, at the end of John’s Gospel he is referred to as “Nathanael from Cana in Galilee” (John 21:2) implying he lived fairly locally to Jesus.

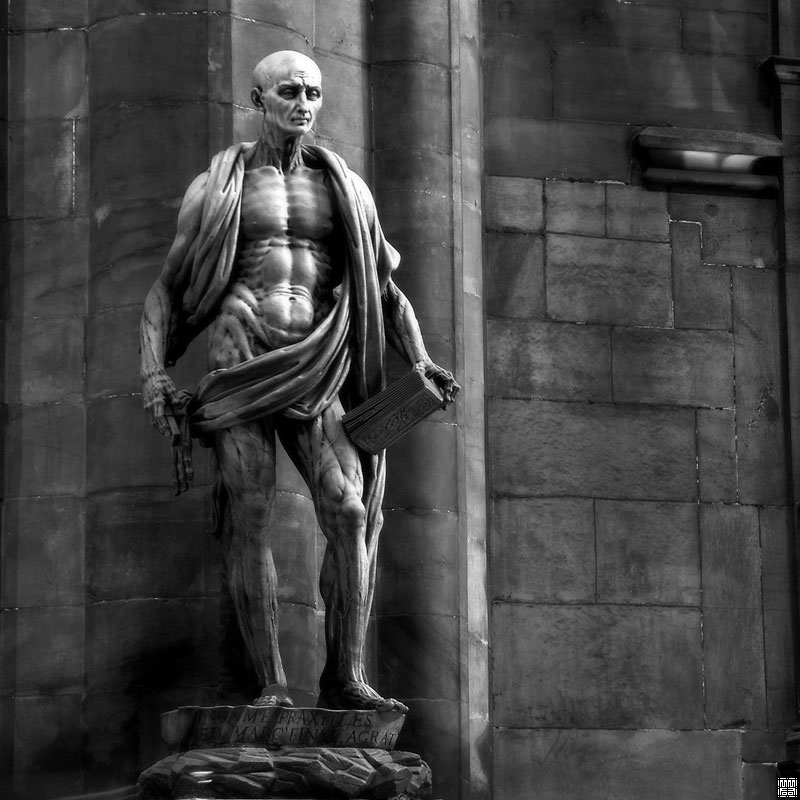

It is not certain why Bartholomew has two names, however, the meaning of the names may give us a clue. Bartholomew is an anglicised version of Bar Talmai, which means either “Son of Talmai” or “Son of Furrows”. It is possible that Bartholomew’s father was called Talmai, which was an Aramaic form of the name Ptolemy. Nathanael, on the other hand, means “God has given” but whether he had this name before he met Jesus is unknown and why it was only John’s Gospel that used it is another mystery. When Bartholomew/Nathanael was first called to be a disciple, he was sceptical, asking, “Nazareth! Can anything good come from there?” (John 1:46) Nazareth was not a particularly well-off place at the time and Nathanael could not believe the true Messiah would come from such a place. “When Jesus saw Nathanael approaching, he said of him, ‘Here truly is an Israelite in whom there is no deceit.’” (John 1:47) Nathanael was surprised that Jesus knew him, so Jesus clarified, “I saw you while you were still under the fig tree before Philip called you.” (1:48) From that moment, Nathanael believed Jesus was the Messiah but Jesus tells him, “You believe because I told you I saw you under the fig tree. You will see greater things than that… Very truly I tell you, you will see ‘heaven open, and the angels of God ascending and descending on the Son of Man.” (1:50-51) So, that is how Bartholomew became a disciple, however, nothing else is said of him in the Gospels other than to list him with the other apostles. Bartholomew’s life after the death and resurrection of Jesus has been pieced together by a variety of sources, however, none of them are completely reliable. The Christian historian Eusebius (c.260-340) claims Bartholomew went on a missionary trip to India, where he left a copy of the Gospel of Matthew. Saint Jerome (347-420) agrees with this claim, however, other sources record Bartholomew serving as a missionary in Ethiopia, Mesopotamia, Parthia (Iran), Lycaonia (Asia Minor) and Armenia. Popular legend believes Bartholomew travelled to Armenia with the apostle Jude where they preached about the life of Jesus. It was also in Armenia where he met his death, either from being flayed alive and beheaded or crucified upside down. Bartholomew had reportedly converted Polymius, the king of Armenia, to Christianity, which enraged his brother Prince Astyages. Yet, this does not match historical records of Armenian kings; there was no King Polymius. In India, however, there was an official named Polymius and some scholars state Bartholomew most likely died there in the town of Kalyan. A few texts record the miracles Bartholomew may have performed before and after his death. The two most popular post-death miracles occurred on the Aeolian island, Lipari. On Bartholomew’s feast day (24th August), the people of Lipari were taking part in an annual procession from the Cathedral of St Bartholomew to the main part of the town, carrying a golden statue of the saint. The statue was usually easy to carry, however, on this occasion, it was too heavy and the bearers had to stop and rest a couple of times, delaying the procession. Whilst resting, at the top of a hill, the walls of the town downhill started to collapse. If the people of Lipari had been in the town at the time, they would all have been killed. They believed Saint Bartholomew had saved their lives by making the statue too heavy to carry. The second miracle on Lipari occurred much later during the Second World War. Fascist leaders needed money and ordered a silver statue of Saint Bartholomew to be melted down, however, when it was weighed they discovered it was only a few grams and not worth the effort. The statue was returned to the cathedral but locals knew the statue weighed several kilograms Once again, they believed Saint Bartholomew had altered the weight of the statue. Despite not much being known about Bartholomew, he has been a popular figure in art. In a biography of the disciple by Jacobus de Varagine (1230-1299), Bartholomew’s supposed appearance was described in detail. "His hair is black and crisped, his skin fair, his eyes wide, his nose even and straight, his beard thick and with few grey hairs; he is of medium stature..." Many artists since have used this description when depicting Bartholomew in their paintings. He is also often depicted as being flayed alive. Contemporary artists have also been inspired by Bartholomew’s fate, including Damien Hurst and Gunther Von Hagen, the developer of the exhibition Body Worlds. Due to the legends, Bartholomew was made the patron saint of the Armenian Apostolic Church. He was also celebrated in England, for example, the Bartholomew Fair, which was held in Smithfield, London during the middle ages. St Bartholomew's Street Fair continues to be held annually in Crewkerne, Somerset and is believed to date back to Saxon times. The nature of Bartholomew’s death led him to be made the patron saint of tanners, plasterers, tailors, leatherworkers, bookbinders, farmers, house painters, butchers and glove makers. Just for fun, here are some of the other things and places that have claimed him as their saint:

“The next day Jesus decided to leave for Galilee. Finding Philip, he said to him, ‘Follow me.’” (John 1:43) Not much is known about Philips origins other than he came from Bethsaida in Galilee, the same place as Andrew and Peter. Having a Greek name, Philippos, suggests Philip may have originally come from Greece. Although there is no evidence to support this, when a group of Greeks wanted to visit Jesus, it was Philip they approached. “They came to Philip, who was from Bethsaida in Galilee, with a request. ‘Sir,’ they said, ‘we would like to see Jesus.’” (John 12:21)

Philip only gets a brief mention in the Synoptic Gospels and it is only in the Gospel of John that his presence is recorded at certain events. Not only was Philip present at the feeding of the 5000, but it was also Philip Jesus turned to ask, “Where shall we buy bread for these people to eat?” (John 6:5) Philip thought the task was impossible, replying “It would take more than half a year’s wages to buy enough bread for each one to have a bite!” (6:6) John’s Gospel, however, reveals Jesus already had a plan and was testing Philip’s faith. At the last supper, Philip said to Jesus, “Lord, show us the Father and that will be enough for us.” (John 14:8) Jesus’ response suggests he was not pleased with Philip’s request: “Don’t you know me, Philip, even after I have been among you such a long time?” (14:9) This, however, prompted Jesus to teach his disciples about the unity of the Father and the Son: “Believe me when I say that I am in the Father and the Father is in me; or at least believe on the evidence of the works themselves.” (John 14:11) The final time Philip is mentioned in the Bible is in the Acts of the Apostles shortly after Jesus had been taken up to heaven. The apostles met up to talk, pray and decide who would replace Judas Iscariot as the twelfth disciple. After this, Philip is never mentioned again by name, however, in Acts 6 “the twelve” came together to appoint seven men to help spread the ministry of the word of God. Whenever the apostles are referred to as “the twelve” it is safe to assume Philip was amongst them. Confusingly, one of the men chosen was also called Philip (the Evangelist), who continues to be mentioned in the Book of Acts. Some extra-canonical texts mention Philip, however, scholars have had difficulty differentiating between Philip the Apostle and Philip the Evangelist. Some historians have even suggested they were the same person; therefore, many texts cannot be fully trusted. The non-canonical Acts of Philip is believed to be an account of the preaching and miracles of Philip after the resurrection of Jesus. The text claims Philip and Bartholomew, one of the other twelve, were sent to preach in Greece, Phrygia and Syria. It also says Philip’s sister Mariamne went with them, however, Mariamne was a name commonly used in the Herodian royal house, therefore, the author may have confused Philip the Apostle with Philip the Tetrarch (26 BC-34 AD). Whilst Philip was preaching in Hierapolis in Phrygia, he converted the wife of the proconsul. This, however, angered the proconsul who ordered Philip to be tortured and killed. There are two versions of his death, one being that he was beheaded. The other, according to the Acts of Philip, claims Philip was crucified upside-down. He continued preaching whilst nailed to the cross, which converted a few more people who tried to release him; however, Philip insisted they leave him and eventually died. His year of death is recorded as 80 AD. Due to his crucifixion, Philip is associated with the symbol of the Latin Cross. He is also symbolised by two loaves of bread or a basket filled with bread due to his part in the feeding of the 5000. Another extra-biblical text, known as the Letter from Peter to Philip, suggests Philip had departed on a solo mission at some point between Jesus’ resurrection and being taken up into heaven. The letter from Peter asks Philip to re-join the disciples at the Mount of Olives, presumably so they could appoint a new disciple. In 2011, Turkish archaeologists claimed to have discovered the tomb of Saint Philip in the ancient town of Hierapolis, near the modern town of Denizli. Writings on the wall of the tomb have provided enough evidence for other archaeologists to agree that it was the final resting place of the apostle. Saint Philip’s relics, however, are kept in the crypt of the Basilica Santi Apostoli in Rome. The Roman Church venerated Philip and 1st May was designated as his feast day, although this has now changed to 3rd May. Eastern Orthodox churches, however, celebrate Saint Philip on 14th November. Just for fun, here are the few things that claim Saint Philip as their patron: · Cape Verde · Hatters · Pastry Chefs · San Felipe Pueblo in New Mexico, USA · Uruguay |

©Copyright

We are happy for you to use any material found here, however, please acknowledge the source: www.gantshillurc.co.uk AuthorRev'd Martin Wheadon Archives

June 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed