Are you the kind of person that struggles with networking? Do you have to strain to come up with satisfactory conversation starters? Is making business deals with other people something you find challenging? Then Networking Thoughtfully is exactly what you need. This short book by Martin Wheadon is a guide for people who need to build relationships but do not know where to start. With simple points, Wheadon takes readers through a step-by-step process to help achieve positive results.

With over thirty thoughts, the reader is taken through clever ideas to boost their confidence and communication skills. The advice is written clearly, accompanied with examples to help get the most of the author's guidance. The tone of the writing is almost conversational, resulting in the sense that the author understands your anxieties and is talking from personal experience. Although written with business gain at the forefront, Networking Thoughtfully can also be used to aid personal development. Learning how to start conversations and come up with ways to introduce yourself is beneficial when meeting new people regardless of the circumstances. The book itself is set out neatly making it easy to follow. It is also easy to dip in and out, reading only the parts relevant to yourself, though if you wish to read it cover to cover it will only take half an hour. Whether you are new to networking or want to improve your skills, Networking Thoughtfully is an excellent book to read. You are guaranteed to learn something new and develop techniques that benefit both your business and yourself.

0 Comments

"Just because the men have gone to war, why do we have to close the choir? And precisely when we need it most!"

Set in the fictional village of Chilbury, Kent during the Second World War, The Chilbury Ladies’ Choir explores the lives of the women left behind whilst the men go off to fight. The remaining villagers are disappointed at the closing of the church choir, which, according to the vicar, cannot go on without any men to sing the tenor and bass parts. However, the arrival of bold, forthright Primrose Trent brings the birth of a new choir, a choir for women only. Although a war is going on, the ladies of Chilbury have so many other things on their minds. Told through a conflation letters and diary entries, The Chilbury Ladies’ Choir reveals the everyday lives of a handful of characters. Mrs Tilling’s journal provides an overview of the general events, whilst 18-year-old Venetia’s letters divulge the wiles and charms she uses in the name of romance. Other characters, particularly the young teenager, Kitty, offer other insights to the goings on in the village. From falling in love, to having babies, The Chilbury Ladies’ Choir is full of secrets, schemes and misunderstandings that almost let the villagers forget there is a war on. However, the effects of war do reach the little village, bringing with it terror and grief. The individual stories that make up the book provide the reader with a number of scenarios that are full of emotion, but equally entertain. One moment the horror of war could leave readers in flood of tears, the next, Mrs B.’s pretentious personality and vaunting comments bring amusement and laughter. All the while these events are playing out, the Chilbury Ladies’ Choir pulls the women together, providing them with a source of comfort to get them through the terrible times. No matter what disasters befall them, whether caused by war or their own actions, joining together in song gives them a purpose and opportunity to have a break from their fears and grief. War may destroy, but they will carry on singing. Written in the manner of private letters and journals gives the novel a personal touch. The story is not merely narrated, it is expressed through the emotion and feelings of individual characters, making the scenarios seem more authentic. The downside to this method is the lack of distinction between each character’s voices. With no detectable dialect, the musings of a 13-year-old are composed in much the same manner as the much older Mrs Tilling. The Chilbury Ladies’ Choir is an enjoyable piece of historical literature, which is bound to appeal to many people. Although set during World War II, its primary focus is on the people in the village, making it more attractive to readers who are fed up of reading about bombs and fighting. A mix of family issues, bribery and romance provide considerably more entertainment than a generic wartime novel. Being Jennifer Ryan’s debut novel, The Chilbury Ladies’ Choir is of a quality that suggests the author has so much more to deliver in the not-so-distant future. Notes from an address by the Rev. Ronald M. Ward, B.D. October 1925, Romford URC I want to discuss with you three ways in which people sometimes react to troubles. Let us call them the way of the Stoic, the way of the Jew, and the way of the Christian.

Although Jeremiah certainly had no spiritual affinity with Stoicism there is a text in the book bearing his name which expresses very well what I mean by the way of the Stoic. It reads like this. "Woe is me for my hurt! My wound is grievous: but I said, Truly this is a grief, and I must bear it." (Jeremiah 10:19) Thousands of people with no religious faith show admirable courage in the face of suffering and loss by adopting this attitude. They bear their troubles manfully and in silence. Sometimes they even grin and bear them. They scorn to whine or complain or look for pity, feeling that the dignity of a human being forbids it, and in this matter many pagans put some Christians to shame. Theirs is part of the routine heroism of the world. It happens every day, is not confined to religious people and does not depend on a divine revelation. But nevertheless this is a threadbare cloak to draw about oneself when the wind is bitter. What else has religion to offer? The Jew strove to adjust himself to all kinds by accepting it as from the hands of a just and holy God. This point of view is well expressed in the book of Job, where Job says, "Shall we receive good at the hand of God and shall we not receive evil?" In this attitude great strength and consolation is sometimes found. Submission to the will of an all wise Creator whose decrees must never be questioned gives to many the courage they need to get through life. A glance at the hymn book, and conversation with many Christians, will show that this essentially Old Testament idea is sometimes not much enlarged by an experience of the Christian Gospel. In fact some Christians deal with misfortune as a Jew might. They know nothing better than to attempt submission to the will of a God who "knows best". Hymn Thy Way, not Mine is full of the atmosphere of a patient submission. Thus verse four reads, Take Thou my cup, and it With joy or sorrow fill, As best to Thee may seem; Choose Thou my good and ill. Some Christian buttress this thought by reflecting that our true joys are in heaven, not in this vale of sorrows, and that it is wrong to expect much happiness on earth. Hymn I'm But a Stranger Here begins in this not very inspiring strain: - I'm but a stranger here, Heaven is my home; Earth is a desert drear, Heaven is my home. The question is whether Jesus thought the earth was a desert drear, and whether the highest Christian ideal in face of sorrow is truly expressed in the prayer for a "heart resigned, submissive, meek." I do not wish to imply that there is no truth or health in this sentiment. A Christian no less than a Jew desires to accept the will of God and knows that "now we fight the battle, but then shall wear the crown." Nevertheless an emphasis upon acceptance of sorrow is not, as I hope to show, a fully Christian one, and may imply a sub-Christian conception of God. Now let us turn our thought to the words of Jesus, uttered, according to the Fourth Evangelist, on the occasion of His arrest. "The cup which my Father has given Me, shall I not drink it?" This was said to Peter, who wished to resist with violence, and it seems at first sight to imply the Cross ought to be accepted as from God. But God did not nail Jesus to the Cross. His enemies did that. We cannot identify the will of God with the will of Caiaphas. That His Heavenly Father required of Jesus an obedience which would involve the Cross, and that the Cross was made to serve the highest Divine purpose, is true. But that is very different from supposing that in the hour of His Passion our Lord accepted suffering as an act of God. No sorrow is like unto His sorrow, but here at the Cross we may reverently learn something of the Christian approach to all suffering. In the first place many things are permitted by God which are not willed by Him. In our darkest hour let us at least remember that. We are to trust Him as a Heavenly Father in all circumstances. But we are not to suppose that all circumstances come from His hand, although all circumstances are in His hand. Most of our troubles can be traced back to human ignorance, or sin or foolishness (our own or another's, or that which belongs corporately to the race); or else to laws of nature which operate, I incline to believe, in a certain measure independently of God. We are often dishonest with ourselves when we forger this. Sometimes what people finally resign themselves to as the will of God is something they have been doing everything in their power to avoid. In fact we often attribute to the will of God those things which we cannot control, and for no better reason. At the present time thousands of human beings die every year of cancer, and Christian people contribute money to cancer research in the hope that a cure may be found. And yet in how many homes is a loved one who died of this disease spoken of as "taken" by God? People who say they cannot understand why such as good man should have suffered so much imply that their sorrow is due to a Divine decree. In that case every penny contributed towards cancer research is an attempt to frustrate the will of God. And if we shrink from such a blasphemous absurdity let us also shrink from the belief that God "sends" all our troubles to us. The struggle of a protesting, suffering heart to accept some tragic happening as in some hidden way "good" for it can be very distressing and is quite unnecessary. Christian piety is not blind obedience to an inscrutable authority, but trust is a heavenly Father. And when it is desperately hard to maintain such a faith try to remember these three simple things. (1) Whatever happens to us God has permitted to happen, though He may not have willed it. (2) God can use what has happened, even when it is not His will, so that in the end it will be seen to have served His purposes. (3) Ultimately God's will must prevail, and even now, since evil and suffering only exist by permission and not in their own strength, God is in complete control. This, however, is only one side of the Christian response to suffering, and it is the negative side. Jesus accepted the Cross, indeed He took it up, as the inevitable result of obedience to God. But He did more than receive it. He also offered it, as at the Last Supper when He gave the cup to His disciples and bade them share it amongst themselves, telling them that His death was to be something accomplished on their behalf. Of course it is futile to compare the sufferings of Christ with ordinary human experience. But in the fact that His cup was both received and offered we may learn something which has a practical application to ourselves. The most Christian response to suffering is surely to ask oneself, not "How can I put up with this?", but "How can I offer this to God? In what way can it be found that a trouble can be turned into an offering, and in so doing we transform it into a creative source of life for other people instead of a drag upon ourselves. I think, for instance, of a woman lying in a hospital ward for many months, her twisted body offering vert little hope of future happiness for herself. And yet it was quite from her cheerful and trusting spirit that she was determined to do something with her situation which would be of service to other people. I think she was a source of courage and reassurance for everyone else in that place. I believe her life was a daily offering to God. A pagan can bear his troubles manfully. A Jew can submit to them obediently. But only a Christian can offer them lovingly. "If I stoop Into a dark, tremendous sea of cloud It is but for a time; I press God's lamp Close to my breast; its splendour, soon or late Will pierce the gloom: I shall emerge one day." Charles Spurgeon was a 19th-century preacher known as the “Prince of Preachers” among many denominations. Spurgeon was mostly involved with the Reformed Baptist tradition, also known as Particular Baptist, and spent a great deal of time opposing the increasingly liberal and pragmatic theological trends in the churches of the day. Many books containing his sermons have been published and read by many generations and Spurgeon continues to inspire people today.

Charles Haddon Spurgeon was born to John and Eliza Spurgeon in Kelvedon near Braintree, Essex on 19th June 1834, although his family relocated to Colchester before his first birthday. Although the Spurgeon family considered themselves Congregationalists, it was not until Charles was 15 that he opened his heart to God. This came about when he was forced to shelter from a snowstorm in a Primitive Methodist chapel. It is said that while he was waiting out the storm, Spurgeon came across the verse Isaiah 45:22 and was immediately converted. "Look unto me, and be ye saved, all the ends of the earth, for I am God, and there is none else." In May 1850, Spurgeon was baptised in the River Lark at Isleham, Cambridgeshire. The same year, he moved to Cambridge to become a Sunday School teacher. That winter, at 16 years old, he preached his first sermon, and thus began his preaching career. His style and insight into the Bible were said to be far above average, not just for his age but in comparison to preachers in general. In 1851, he was made the pastor of a small baptist church in Waterbeach, Cambridgeshire and published his first book, which focused on the Gospels, in 1853. Aged 19, Spurgeon was called to become the pastor of New Park Street Chapel, Southwark, London, which had the largest Baptist congregation at the time. Here, his preaching ability became famous and his sermons were so popular that the "New Park Street Pulpit" began to publish one every week, selling them for a penny each. Later, books were published under the same title as the weekly publication, featuring five volumes of Spurgeon’s sermons. It is estimated over 3,600 of his sermons were printed during his lifetime. Naturally, with greatness came criticism from those who thought Spurgeon’s sermons were too straightforward. Nonetheless, they appealed to the congregation, which had grown to a size of 10,000 by Spurgeon’s 22nd birthday. Unable to fit everyone into the building, the church moved to Exeter Hall on the strand, then the Surrey Music Hall in Newington in order to accommodate everyone. The year 1856 began positively with Spurgeon’s marriage to Susannah Thompson, however, it ended in tragedy. During one of Spurgeon’s sermons at the Surrey Music Hall, someone in the crowd shouted “Fire!”, which spread mass panic and hysteria. Thousands of people immediately ran for the exit, pushing those in their way and crushing anyone who had fallen. Several died as a result and Spurgeon was mentally affected by the scene for the rest of his life. He admitted to sudden, unexplainable tears, which today doctors may identify as a symptom of depression or PTSD. Nonetheless, Spurgeon persevered with his preaching and the following year became the father of twin boys: Charles and Thomas. The same year he founded a pastors’ college, which was renamed Spurgeon’s College in 1923, and, in October, preached to his largest congregation yet. The service took place at The Crystal Palace and welcomed an estimated 23,654 people. Spurgeon’s church could not remain at the Surrey Music Hall forever, so on 18th March 1861, it moved to the purpose-built Metropolitan Tabernacle in Elephant and Castle. The Independent Baptist Church still worships there today. Spurgeon preached there several times a week for the remaining 31 years of his life. The reason it was possible to publish so many, if not all, of Spurgeon’s sermons, was because he wrote them out before each service. When he reached the pulpit, however, all he had with him were a handful of notecards to prompt him, suggesting he had learnt the sermon off by heart. As well as sermons, Spurgeon wrote a handful of hymns, however, he preferred to use popular songs by other writers, such as Isaac Watts. They were mostly sung a capella due to the lack of an organ in the church. Spurgeon did not limit himself to Baptist congregations and frequently preached to other denominations. Nonetheless, his sermons often argued against some of the methods of preaching used by the Church of England. One argument was that a person did not have to be baptised in order to experience salvation. Not only did this argument go against the Church of England, but it also angered other Baptist churches. As a result, the Metropolitan Tabernacle removed itself from the Baptist Union, becoming an Independent Baptist Church. Through his popularity, Spurgeon made many connections with other preachers and philanthropists. He supported the China Inland Mission founded by his friend, James Hudson Taylor, and was inspired by Christian evangelist George Müller to open an orphanage. The orphanage was closed after the Second World War and became Spurgeon’s Child Care charity, which continues to support vulnerable families, children and young people in the United Kingdom. Spurgeon was vocally against slavery, which lost him a few supporters, particularly those from the United States. “... although I commune at the Lord's table with men of all creeds, yet with a slave-holder, have no fellowship of any sort or kind. Whenever [a slave-holder] has called upon me, I have considered it my duty to express my detestation of his wickedness, and I would as soon think of receiving a murderer into my church . . . as a man stealer.” (Spurgeon, Christian Watchman and Reflector, c.1860) Although Spurgeon had the support of his family, his wife was often too ill to leave home and attend his sermons. Yet, she outlived her husband who suffered from rheumatism, gout and Bright's disease in his later years. Spurgeon began making regular trips to the French Riviera to ease his symptoms, which is where he was when he died on 31st January 1892. Spurgeon was buried in West Norwood Cemetery, one of the “Magnificent Seven” cemeteries in London. His son, Thomas, took his place as the pastor of the Metropolitan Tabernacle. Famous sayings of Charles Spurgeon:

Questions suggested by Dwight L. Moody (1837-1899)

These notes were found in the September 1952 issue of Progress, the monthly magazine of the Romford Congregational Church. They come from an address given by the Rev. Ronald Ward at the Annual Conference of the Guild of Heath 1. The Biblical View of History

The Biblical view of History can best be indicated by comparing Isaiah 40:3-4 with the first chapter of Ecclesiastes. The writer of this section of Ecclesiastes, though a Jew, has a pagan spirit. For him there is "no new thing under the sun". History can best be represented as a circle. "The thing that hath been it is that which shall be". Deutero-Isaiah, on the other hand, has a view of history which is Biblical through and through. The verse containing the words "make straight in the desert a highway for our God" sums up the whole matter. In this thought history may best be symbolised not by a circle but by a straight line. The human race is on a road, not a roundabout. History is moving towards an ultimate and triumphant conclusion. Time is therefore an all important element in experience, and this is why the Biblical writers are in the main concerned with meaningful events rather than ideas. Western man derives his view of history, and in particular his conception of progress, from the Bible. 2. The Lord of History The Biblical view of history is accounted for by the Biblical view of God. God is creator and Lord of History. As creator He is necessarily above events in this world, and ultimately in control of them. Nevertheless the Bible stresses the immanence of God, and reveals Him as actively at work within world events. 3. The Holy Spirit History To say God is active in History is to say that the Holy Spirit is active there. For the Holy Spirit is not a vague influence for good, but the life of God Himself as actually encountered by us in the world. Two things are to be observed about the world of the Holy Spirit.

In addition to this it should be noted that the Spirit is thought of as active in all the works of nature, as well as in personal life. But then the natural world only comes into existence through the Word of God. "God said, Let there be light, and there was light". The Bible would have us recognise the activity of the Holy Spirit in history through the following Divinely elected ways.

4. The Holy Spirit in the Church Henceforth the Holy Spirit, though active everywhere, is shaping the course of history through the New Israel, the Christian Church. The Church alone has heard and received the full Word of God which is in Christ, and therefore it is through the Church that the Spirit will realise the Kingdom of God on earth. That is why Christianity is, in Christopher Dawson's phrase, "a world changing religion". The restless enterprise of Western man, though seldom related to religious ends and often evil in its result, is nevertheless due to the impact of Christianity. It is no coincidence that empirical science has flowered in the West and not the East, where religion preserves a static culture for centuries, but provides no impulse for bringing a new kind of world into existence. For the religions of the East time is an illusion, For the Christian faith time, and therefore history, is the loom of God. 5. The Holy Spirit in the Contemporary Situation Today Christianity exists under the menace of atheistic Communism. It must be remembered that the Communist view of history is in many essentials derived from the Bible (Marx was a Jew). This accounts for its dynamic and revolutionary character. Communism is a perversion of Christianity. But if God is the Lord of History the present situation has not emerged by accident and cannot get out of control. There is a Word of judgement in it - upon the world, because it has rejected Christ again in this generation, but also upon the Church because it has sought to accept Christ on its own terms. The Holy Spirit is certainly active in the present scene of world affairs - perhaps forcing us, through events, to take Christianity seriously once and for all. Rest assured that the Work of the Spirit, which we have seen running like a thread through all the centuries, cannot be frustrated by anything men have power to do. History will not end with an atom bomb. It will end when He who began it has finished what He is doing in it. A surprising amount of people read and believe in the New Testament but reject or ignore the Old Testament. God gets split in two, becoming the God of the Old Testament and the God of the New Testament. The focus turns to Jesus and everything that came before gets relegated to "stories". Yet, without the Old Testament, there would be no New Testament. Did you know, of the 39 books in the Old Testament, Jesus quoted from or referred to 22 of them? During his lifetime, he may even have quoted from all of them for, as John says in his Gospel, "And there are also many other things which Jesus did, which if they were written in detail, I suppose that even the world itself would not contain the books that would be written." (John 21:25)

Here are some other links between the Old and New Testaments:

Jesus often referred to prophets of the Old Testament, for instance, "Now He said to them, There are My words which I spoke to you while I was still with you, that all things which are written about Me in the Law of Moses and the Prophets and the Psalms must be fulfilled." (Luke 24:44) Without the Old Testament, there would be nothing to fulfil. In the Gospel of Luke, Jesus explained to the disciples on the road to Emmaus that it was necessary for Christ to suffer. "Then beginning with Moses and with all the prophets, He explained to them the things concerning Himself in all the Scriptures." (Luke 24:27). As the preacher Dwight Moody once said, if Jesus Christ could use the Old Testament, let us use it. Do not neglect the Old Testament. The following extract comes from the book How to Study the Bible by Dwight L. Moody. If you are impatient, sit down quietly and commune with Job. If you are strong-headed, read about Moses and Peter. If you lack courage, look at Elijah. If there is no song in your heart, listen to David. If you are a politician, read Daniel. If you are morally corrupt, read Isaiah. If your heart is cold, read of the beloved disciple, John. If your faith is low, read Paul. If you are getting lazy, learn from James. If you are losing sight of the future, read in Revelation of the Promised Land.

This article was found in the August 1952 issue of Progress, the monthly magazine of the Romford Congregational Church. The following address was given by Mr. Ebenezer Cunningham, a Deacon of Emmanuel Church, Cambridge. That there is something different between the relationship of minister and people in a Congregational Church and the relationship which one obtains in an Anglican Church is fairly apparent. It shows us clearly in the way in which a member of the Anglican Church will speak to his minister as "Vicar", while we should almost invariably address him as "Mr. Smith", or as often happens in these days, as "John" or "Eric". In the former case he is the official representative of the Church. In our case, he is a friend and equal among us. And of course this is related to the difference in the way in which he comes among us as compared with the advent of a vicar. The bishop appoints a vicar. The Congregational Church invites a minister. Our Anglican friends would perhaps consider that our way is informal and lacking in weighty sanction. But in principle, though not always realised in practice, the invitation of a minister to a Congregational Church in the action of the Church, of the members covenanted together in Christ under the guiding of the Holy Spirit. It is one of the most solemn actions of a church. It is the action of the Church in its most complete sense. This is evident in the way in which, for a great many Churches, notice is given publicly at each service on two Sundays previously of a special meeting for the consideration of a call to a minister. The call, like all subsequent relations with a minister is conditioned by all the frailty and failings of ordinary people; but in this matter, as in every true Church meeting, the members are acting at their highest level, Indeed, that the Church is wise which never sends a call except on the unanimous feeling of the meeting.

And the minister, on receiving the call, awaits the guidance of the Holy Spirit, that he may reply rightly. And if he accepts the call, he trusts himself into the keeping of the Church, for good or ill, to serve and not to count the cost. It is a solemn engagement into which minister and people enter. They become responsible to, and responsible for each other. The minister becomes a member of the Church on the same terms as any other, entering into the same covenant with the Church to walk together in the ways of Christ and to be guided by the one spirit. And so the first element in the relationship of minister and people is the same as the relationship between any two members of a Church. This, of course tells both ways. It raises the conception of the relationship between any two members to the level at which each ministers to the other. It is said that "there is no laity." We are all ministers. This is a fact which we often lose sight of. But if it became a reality among us or in proportion as it does so, we are realising the true nature of the Church. Feebly we try to make it so. But how much further do we need to go? And so our first duty to our minister is to minister to him. We have to minister to his ordinary needs and the needs of his family. We become responsible for his house and home, for his food and raiment, as we are responsible to our own family. This needs be said: "The first call on the members of the Church financially is the maintenance of the minister." As a member of the Home Churches Fund Committee I have heard so much of the Churches who say we cannot pay more towards the support of our minister because of the dry-rot in our roof, or the breakdown of our heating system, or a £400 bill for repairs. Of course the whole financial set-up is involved. The care of the buildings entrusted to us by our fathers is one that has to be lovingly dealt with. But as a matter of fact we do not care for them enough. We let them get into disrepair, then have a big bill and make that a reason for special efforts, draining our strength, when we should prudently, over a period of years, have been gradually building up a repairs fund against the time of need. And in this prudent budgeting for the whole life and maintenance of the Church, the care of the minister, whom under the guiding of the spirit, we have asked to come and serve us, deserting all else, must have the highest priority. I would say that even then poorest of our Church members should not feel satisfied in these days at devoting less than a shilling a week to that part of the life of the community; and thereafter asking what is due for the work of Christ in the Church. At the least, the labourer is worthy of his hire, and this is a relationship far closer than that of a hired labourer. And it is a relationship far higher than that of charity. There are those who, conscious that a minister is poorly paid compared with themselves, like to give him presents from time to time. But let us make quite sure that he is paid in such a way that he is on equal terms with ourselves. We all know pretty well the sort of standard which is an average one in our own Church. But the minister has needs other than physical to which we have to minister. How much do we expect of him? He has a limited amount of time, strength and energy as we all have. Mentally and spiritually his output is limited, and may be cut down if we impose strains upon him. But it may be increased by the power of the Spirit and of the spiritual atmosphere with which we surround him. If he is left to plough a lone furrow, he will tire and lose heart. But if he is one of a team, the yoke will be easy, and the furrow straight. So we have a spiritual ministry to render to him; and this is the most important part of our responsibility to him. How do we exercise it? This is for us lay-folk the question to which we should give most attention, and on which our discussion might well focus. I can only make one or two suggestions. I remember at the preaching-in of a new young Scottish minister, the preacher gave to the Congregation the charge "Love your young minister." Young or old or middle-aged every minister needs love. And love in the deepest sense. And that is really the sum of the whole matter. Perhaps the first element in such love is thoughtfulness, putting yourself in his place. Imagine his life. With all the distractions of home and children, all the consciousness of his wife's labours, all the failings of his own nature as husband and father, and of his wife's nature, he has to carry on and seem undisturbed. With the care and love which his wife lavishes on him, and what a miracle this is, he is painfully conscious of his position and what people expect of him. (If perchance he is a bachelor his plight is worse, with all those temptations that assail a man who lives by himself.) Picture him getting up, with morning devotions, fireplaces, breakfast, washing up, making beds, carrying coals all competing for him, and his study waiting for him and the newspapers and letters with tales of woe coming between him and settling down to his preparation for Sunday. Think of the problem of keeping fresh so that life is for ever providing him with more situations which he has to enlighten from the Word of God. Think of the telephone going, the callers for advice, the sick people to visit, the aged and those who expect to be visited. And then think of him planning for the life of the Church, looking forward to ask where the new members are coming from, bearing each separate young person in mind, and the children's Church, and the casual and slipping members. All these and how much else is on his mind and heart. And what do we do about it? What can we do about it? Can we make his care our own? For they are the cares of the whole family of the Church. Our ministry to him must be not that of expecting to get, but desire to give. It must be an out-going friendship towards him. He must know that we care, that in our measure we will bear the burdens. There will be many that he has to carry about in the secret of his heart. There are others which he should know that he may look to us to share or bear. There must be some among us to whom he can unburden himself, even to bringing that of which he is ashamed with the knowledge that Christ is present as he talks. And all this means that we shall realise the depth of our relationship in proportion as we ourselves are brought nearer to Christ himself. As that happens, any critical spirit will fade out. As that happens, he will not have to search among unwilling helpers for the man for the job. As that happens, suggestions and plans for a forward move will come from us, we shall cease to be passengers to carry, but men who ply an oar. Of course there are some of us who are too forward with suggestions, and whose judgement is not always of the wisest. Perhaps these of us are more trying than the inert and ineffective. The pugnacious deacon, the difficult deacon are thorns in the flesh of the minister. The grumbler and the stick-in-the-mud are always with us. But how else are these to become co-operative and helpful, save for the breath of that same spirit in their hearts which in another diffident and shy member will bring a readiness to come out of his shell? How shall we sum up the relationship which we would hope for between minster and the people? Of course it depends upon your vision for the Church. If you have a static picture of the Church, in which the same things go on always, in which the successive generations come and listen to successive ministers, maintain the same organisations, preserve the customs of the last generation through changing ages, then we shall be the despair of any live minister, and sooner or later we shall break him. If we think of the minister as laying down the law, guiding all that we do, bearing the full responsibility for all the life of the Church, then we shall be tame followers, with no ideas of our own. But if we envisage the Church as the continuing body of Christ, existing to carry on his work of saving the world, then we shall be an eager team, glad of leadership from one who has given all to the work, offering all that we have and are in co-operation, eager to learn, eager to share. Our leader will not lack encouragement, he will be kept on his toes, he will be worked harder than ever, but not occupied in dragging a dead-weight. He will be a trainer of a team, teaching us how to run, showing us where we are clumsy and revealing to us the things that make us less than we may be. Above all he will be keeping us on the way of discipleship of Him who is the great leader and Lord.

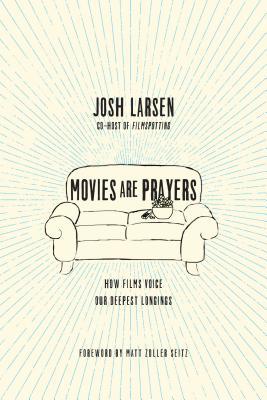

Subtitled How Films Voice Our Deepest Longings, film critic and committed Christian, Josh Larsen, writes Movies Are Prayers to explain his perspective that films are one of our ways of communicating with God. Films, or movies as they are oftentimes referred to in this book, can be many things from a form of escapism to historical information and artistic expression, but as Larsen maintains, they can also be prayers.

“Movies are our way of telling God what we think about this world and our place in it.” Apart from those based on Biblical characters or Christian messages, films are not usually a deliberate attempt at speaking to God. What Larsen is suggesting is that God can be found in places you would not expect – the cinema, for instance. Prayer is a human instinct, even for those who have no religious ties. We are forever asking “why am I here?” or “why me?” alongside feelings of gratitude and love for our positive experiences in life. Josh Larsen explores several expressions of prayer, including the tenets of the Lord’s Prayer, to examine numerous films from popular classics to contemporary Disney. Beginning with wonder at the natural world (Avatar, Into The Wild), positive forms of prayer are identified in well-known cinematography, such as reconciliation (Where the Wild Things Are), meditation (Bambi), joy (Top Hat, and most musicals) and confession (Toy Story, Trainwreck). But Larsen does not stop there, he goes on to use examples of emotions that many may not consider forms of prayer: anger (Fight Club, The Piano) and lament (12 Years a Slave, Godzilla). To back up his theory, Josh Larsen relates film sequences with Bible passages, for example, the prayers of David and Job. He likens the ending of Children of Men with the Christmas story and identifies the worshipping of false gods with Wizard of Oz. Larsen also suggests the obedience of the main character in It’s a Wonderful Life reflects the experiences of Jonah. As well as Biblical theory, Larsen refers to citations from other respected Christian writers on the matter of prayer, challenging preconceived notions of both the religious and the atheist. Despite the fact Movies Are Prayers is heavily steeped in religious connotations, it may appeal to film buffs who wish to delve deeper into the hidden meanings of films. Although the examples in this book are mostly well-known titles, it is unlikely that readers will have watched all the films. Helpfully, Josh Larsen provides details and descriptions of the scenes he has chosen to focus on so that even if you are not familiar with the story, it is possible to understand the author’s perspective. Having said that, Movies Are Prayers contains a lot of spoilers. Everyone has their own personal view on Christian theory and prayer, so Movies Are Prayers can only be treated as an idea rather than gospel. However, Josh Larsen has developed an interesting theory that makes you think more about the ways we can communicate with God, even when we may not have deliberately chosen to. Being easy to read and not overly long (200 pages), Movies Are Prayers is the ideal book for film-loving Christians. |

©Copyright

We are happy for you to use any material found here, however, please acknowledge the source: www.gantshillurc.co.uk AuthorRev'd Martin Wheadon Archives

June 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed