|

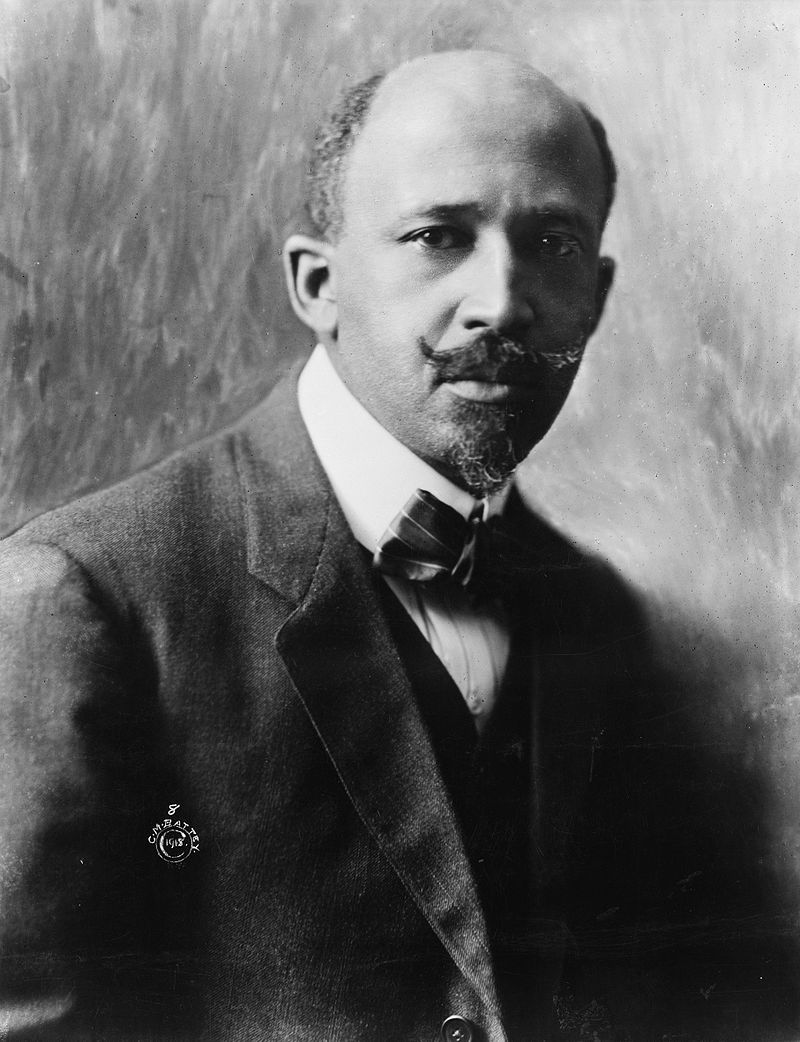

W.E.B Du Bois was the leader of the Niagara Movement, a group of African-American activists campaigning for equal rights. Through his campaigns and essays, Du Bois documented the widespread racism in the United States of America. Ultimately, Du Bois wished to put an end to prejudices, and in the process, educated many people about the inaccuracies of American history, that painted blacks in a bad light.

Born on 23rd February 1868, in Great Barrington, Massachusetts, to Alfred and Mary Silvina Du Bois, William Edward Burghardt Du Bois grew up in a tiny black population. His father left when Du Bois was only two years old, and his mother raised him alone. Fortunately, Great Barrington had a large European American community who treated Du Bois well, and his school teachers encouraged him to pursue his academic studies at Fisk University, a historically black college in Nashville, Tennessee. Du Bois experienced little racism until his time at university where he came face to face with the harshest bigotry. Fortunately, this had little impact on his education and, after Du Bois graduated in 1888, he attended Harvard College, paying his tuition by taking on summer jobs and accepting loans from friends. In 1890, Du Bois graduated with a degree in history. Yet, this was not the end of his education. After another year at Harvard studying sociology, Du Bois received a fellowship from the John F. Slater Fund for the Education of Freedmen to attend the University of Berlin. While in Berlin, Du Bois observed the differences in the treatment of black people. “They did not always pause to regard me as a curiosity, or something sub-human; I was just a man of the somewhat privileged student rank, with whom they were glad to meet and talk over the world.” Racism, he noted, was much worse in the USA. On returning home, Du Bois earned a PhD from Harvard University, the first black person to do so. Following this extensive education, Du Bois received many job offers, including a teaching job at Wilberforce University, Ohio. After working there for two years, Du Bois married one of his students, Nina Gomer, on 12th May 1896 and moved to Pennsylvania to work as an assistant in sociology. Whilst there, Du Bois worked on the study The Pennsylvania Negro, which noted the treatment blacks received in the area. He rejected Frederick Douglass’ idea of blacks integrating into white communities, believing instead that they needed to embrace their African heritage while contributing to American society. He published the latter in his article Strivings of the Negro People in The Atlantic Monthly. In 1897, Du Bois moved to and accepted a job as the professor of history and economics at Atlanta University. The US government gave Du Bois a grant to research African-American workforce and culture, which he did alongside hosting the annual Atlanta Conference of Negro Problems. In 1900, Du Bois flew to London to attend the First Pan-African Conference, which implored the USA to "acknowledge and protect the rights of people of African descent". Later that year, Du Bois attended the Paris Exposition where he organised The Exhibit of American Negroes for which he won a gold medal. By the early 20th century, Du Bois was a respected spokesperson for his race, second only to Booker T. Washington (1856-1915). Du Bois disagreed with many of Washington’s ideas, which asked blacks to submit to white supremacy in exchange for fundamental education. He expressed his criticism of Washington in The Souls of Black Folk in 1903. Du Bois believed blacks should fight for equal rights and opportunities. In 1905, Du Bois met with other civil rights activists in Canada, near Niagara Falls. Together, they established the Niagara Movement, aiming to reach out to other black people through magazines, such as The Horizon: A Journal of the Color Line. Unlike periodicals owned by or sympathetic to Washington, The Niagara Movement encouraged African Americans to stand up for their rights rather than submit to humiliation and degradation. It was not just the Niagara Movement that changed the minds of the African American population. In 1906, President Roosevelt (1858-1919) dishonourably discharged 167 black soldiers for allegedly committing crimes. Following this, riots broke out in Atlanta, where black men received accusations of assaulting white women. Rioters attacked any man with dark skin, resulting in at least 25 deaths. Fuelled by these events and his growing support, Du Bois continued to write about the dangers of white supremacy. He was the first African American invited to present a paper by the American Historical Association. Unfortunately, most white historians ignored his work, and the association did not invite another African American speaker for three decades. In 1909, Du Bois joined the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) and accepted the post of Director of Publicity and Research the following year. This entailed editing the NAACP’s magazine The Crisis, which denounced the US government and introduced the principles of the Socialist Party. Du Bois endorsed Democratic candidate Woodrow Wilson (1856-1924) in the 1912 presidential race, extracting from the future president the promise to support black rights. When the First World War broke out, the NAACP established a camp to train African Americans to serve in the US Army. The government promised 1000 officer positions for blacks, but riots broke out across the country in opposition. Only 600 black officers managed to join the Army. Nonetheless, Du Bois saw this as a success and interviewed many African American soldiers during the first Pan-African Congress. Unfortunately, he discovered many of the officers served as labourers while the white men went out to fight. Du Bois was more determined than ever to fight for equal rights. “But, by the God of Heaven, we are cowards and jackasses if, now that the war is over, we do not marshal every ounce of our brain and brawn to fight a sterner, longer, more unbending battle against the forces of hell in our own land.” Race riots continued to take place across the country, resulting in the deaths of hundreds of black people. As well as wishing to put an end to this unnecessary violence, Du Bois wanted to educate black children about their heritage, teaching them that they did not deserve the racist treatment. As a result, Du Bois published the textbook The Brownies' Book, which was full of black culture and history. After working with the NAACP, Du Bois resigned from his post in 1933 and returned to an academic position at Atlanta University. This allowed him to continue his research, documenting how black people were central figures in the American Civil War and Reconstruction. His magnum opus, Black Reconstruction in America, was published in 1935 and is still perceived as "the foundational text of revisionist African American historiography." In 1936, Du Bois embarked on a trip around the world where he received amicable treatment from people of all races. This was a stark contrast to the treatment of blacks back home. Du Bois admired the growing strength of Imperial Japan and was at first opposed to America joining the Second World War because he thought this would undo Japan’s fight to escape white supremacism. He was also disappointed that blacks only made up 5.8% of the US army. Du Bois openly discussed his strong views in his books and papers, which eventually got him fired from his position at Atlanta University. Fortunately, scholars intervened, and Du Bois received a lifelong pension and the title of professor emeritus. Other universities offered Du Bois teaching positions, but he turned them down and rejoined the NAACP. Du Bois was one of three members of the NAACP to attended the 1945 conference in San Francisco, which oversaw the establishment of the United Nations. The NAACP continued to fight for civil rights, submitting several petitions to the UN. Although the NAACP supported socialism, it made it clear the association had no involvement with Communism. Yet, Du Bois showed sympathy towards the Communist Party, resulting in the loss of his passport. He eventually regained his passport in 1958 and travelled the world with his second wife Shirley Graham Du Bois (1896-1977) who he married in 1951. Nevertheless, when the US upheld the Concentration Camp Law in 1960, requiring all Communists to register with the United States Attorney General, Du Bois joined the Communist Party in protest. At this time, he was 93 years old. In 1960, Du Bois travelled to Africa to celebrate the creation of the Republic of Ghana and to attend the inauguration of the first African governor of Nigeria. The following year, Du Bois took up residence in Ghana to work on the creation of a new encyclopedia of the African diaspora, the Encyclopedia Africana. By this time, Du Bois’ health was declining, and he passed away on 27th August 1963, not long after the US refused to renew his passport. On hearing of his death, thousands of Americans honoured Du Bois with a minutes silence. Almost a year later, the US passed the Civil Rights Act of 1964, representing many of the things Du Bois campaigned for during his long life.

5 Comments

7/25/2021 01:26:45 am

W.E.B is a great source of motivation for us. He was one of the leaders so far. He worked hard to achieve his goals and lead a team of many people. I am a big fan of him and always love to read about this great personality.

Reply

3/7/2022 12:29:52 am

I very much appreciate it. Thank you for this excellent article. Keep posting!

Reply

12/10/2023 03:19:22 am

Thank you for sharing your thoughts. I found your perspective to be refreshing and thought-provoking.

Reply

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

©Copyright

We are happy for you to use any material found here, however, please acknowledge the source: www.gantshillurc.co.uk AuthorRev'd Martin Wheadon Archives

June 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed